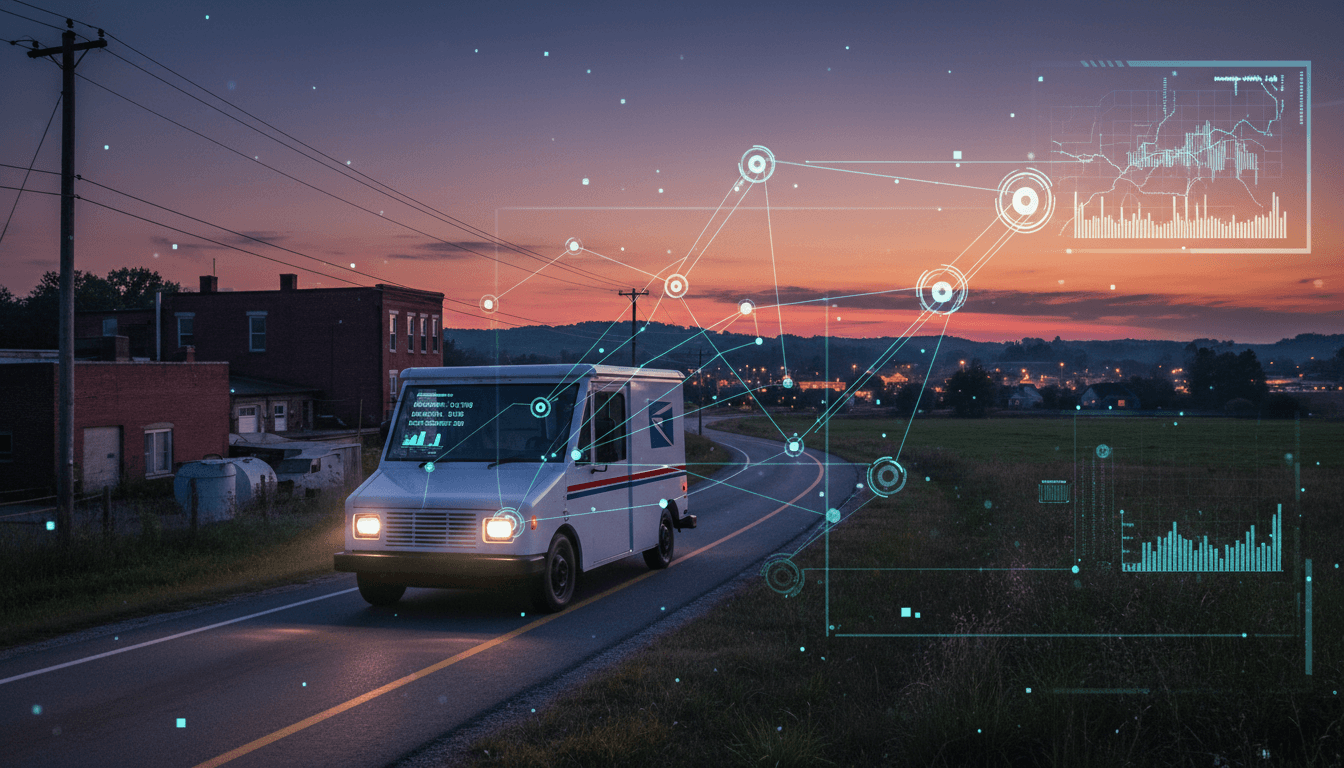

USPS plans to auction last-mile access in 2026. Here’s how AI and analytics can protect service quality while turning public logistics into sustainable revenue.

AI-Powered Last-Mile Access: USPS’ New Revenue Play

USPS delivers to 170+ million U.S. addresses, at least six days a week. That universal reach is an operational marvel—and an expensive one. Now the Postal Service is trying something that’s both practical and overdue: selling broader access to its last-mile delivery network to bring in new revenue.

The timing isn’t subtle. USPS reported a $9 billion net loss in fiscal 2025, and leadership has warned the agency could run out of money in early 2027. Meanwhile, the broader shipping market is changing fast: private carriers are building regional density, retailers are experimenting with micro-fulfillment, and major shippers are reassessing contracts.

For government and public-sector leaders watching AI in transportation and logistics mature, this USPS move is more than a finance story. It’s a case study in how public infrastructure can be monetized responsibly—but only if it’s managed with the kind of data analytics, forecasting, and AI operations that modern logistics now requires.

USPS is monetizing the “last mile” because it’s the hardest part to scale

The core point is simple: the last mile is where delivery costs spike. Every carrier wants dense routes—many stops close together. USPS is the rare network that must serve everyone, including addresses where private delivery is inefficient.

That’s exactly why private companies already use USPS for certain deliveries, especially in harder-to-reach areas. What’s new is USPS’ intent to open and formalize access at scale. The agency has said it will begin auctioning access to more than 18,000 delivery destinations in late January or early February 2026.

From a public-sector logistics perspective, this is a strong strategic stance: you don’t cost-cut your way to sustainability—you design for growth. But growth creates new pressures that USPS can’t manage on spreadsheets and institutional memory alone.

What an “access auction” really implies operationally

An auction isn’t just a pricing mechanism. It’s an operating model.

To make this work without harming service performance, USPS needs to manage:

- Capacity constraints (how much additional volume a destination can absorb)

- Service-level commitments (on-time delivery and scan compliance)

- Network fairness (avoiding a model that only benefits the biggest bidders)

- Operational risk (holiday surges, weather disruptions, labor constraints)

This is exactly where AI and data analytics stop being “nice to have” and become the control system.

The real risk: revenue growth can break service quality without smarter planning

The most predictable failure mode here is also the most common in logistics: adding volume without redesigning the network control layer.

If USPS sells access broadly, it must avoid two outcomes:

- Service degradation (slower delivery, missed scans, carrier overtime spikes)

- Cost surprises (rework, redelivery, exception handling, customer support load)

And there’s another complication: USPS is already executing a long modernization effort, Delivering for America, launched under former Postmaster General Louis DeJoy. Some stakeholders argue it has raised prices and slowed delivery in certain lanes, without achieving the promised break-even trajectory.

So yes—new revenue matters. But revenue that creates operational chaos isn’t revenue; it’s deferred cost.

GAO’s critique points to a data gap AI can help fill

A recent oversight critique highlights a foundational issue: USPS has been faulted for not including near-term financial projections in a strategic plan update, limiting the ability to track progress and communicate how actions improve sustainability.

AI won’t fix strategy on its own, but it can materially improve the rigor of planning by producing:

- Short-horizon forecasts (weeks to quarters) tied to real operational constraints

- Scenario models (what happens if a major shipper exits, or volume shifts regions)

- Cost-to-serve models by route, destination type, and delivery frequency

If you’re selling last-mile access, you need a tight answer to one question: Which marginal packages improve the economics of the route—and which ones make it worse?

Where AI fits: three practical use cases for “smart last-mile access”

The best way to think about AI here is not as a replacement for experienced postal operators, but as the layer that makes a complex marketplace manageable at postal scale.

1) Predictive demand forecasting (especially for seasonal surges)

The Postal Service lives and dies by seasonality. And this week on the calendar matters: mid-December is when networks run hot, exceptions spike, and small errors cascade.

AI-driven demand forecasting helps USPS anticipate volume at the destination and route level using signals like:

- historical scans and induction profiles

- shipper mix changes (new access buyers, reduced volumes from others)

- regional event patterns (storms, local holidays, school schedules)

- operational constraints (staffing, vehicle availability, facility throughput)

If USPS wants auctions to be credible, it needs to set expectations for buyers: capacity is not infinite, and surge rules must be explicit.

2) AI route optimization that respects labor, safety, and service constraints

Route optimization is a classic AI in transportation and logistics use case—but government networks add constraints that commercial models often ignore.

A USPS-grade model must account for:

- delivery windows and service standards

- walk routes vs. curb routes vs. cluster boxes

- overtime rules and union constraints

- safety constraints (weather, daylight, hazardous conditions)

- equity commitments (universal service obligations)

What works in a private fleet simulation can fail fast in a public network if it assumes unlimited flexibility. The goal isn’t “shortest route.” The goal is lowest total cost-to-serve while maintaining service and workforce rules.

3) Dynamic pricing and “access governance” with explainable analytics

An auction can become politically and operationally fragile if stakeholders can’t explain why pricing changes.

AI can support dynamic pricing recommendations, but the model needs guardrails:

- Explainability for auditors and regulators

- Anti-manipulation controls

- Fair access tiers so small and mid-sized shippers aren’t squeezed out

- Clear measurement of incremental cost vs. incremental revenue

A useful north star is: price access based on the true marginal cost of delivery at that destination, not a blanket average. That pushes volume toward economically beneficial lanes and reduces cross-subsidy pressure.

The Amazon factor: dependency risk is the quiet driver of this move

One detail in the public reporting should make any public-sector strategist sit up: a major retailer has been reported as considering whether to renew a large USPS shipping contract expiring in 2026, with estimates that the relationship represented over $6 billion in annual revenue in 2025.

Whether that specific contract changes or not, the broader point stands:

A public logistics network that depends heavily on a small number of mega-shippers is financially fragile.

Opening last-mile access via auctions is one way to reduce concentration risk. But diversification only helps if USPS can:

- onboard many shippers with minimal friction

- enforce consistent induction and labeling standards

- manage exceptions and claims at scale

- maintain service quality under mixed shipper behavior

AI helps here too: it can identify which shippers generate high exception rates, which packaging profiles increase damage, and which induction patterns cause downstream bottlenecks.

What public-sector leaders should learn from this (even outside USPS)

This USPS program is a model other agencies can adapt: monetize underused capacity without undermining the mission.

Here’s how I’d translate it into a practical playbook for government transportation and logistics leaders.

A “sell access” program needs a measurement spine

Before you sell access to public infrastructure—delivery networks, permitting capacity, facility throughput, even call center time—you need a measurement spine that answers:

- What does it cost to serve one more unit of demand?

- Where are the real bottlenecks (facility, route, workforce, IT)?

- What service metrics will not be compromised—and how will you prove it?

If those answers are fuzzy, the program will create controversy, not sustainability.

Build the AI capability like an operations product, not a one-off project

The trap most agencies fall into is treating analytics as a report. A last-mile access marketplace needs an operations product:

- real-time dashboards tied to decisions (accept volume? throttle? reprice?)

- automated exception detection (late scans, facility overload, route drift)

- model monitoring to prevent forecast decay

- governance processes that auditors can follow

This is where leads are actually generated for vendors and partners: not “we did an AI pilot,” but “we run a measurable operational system that improves every week.”

A better way to evaluate USPS’ plan: ask five blunt questions

If you’re a policymaker, oversight professional, or public-sector executive, these questions cut through the noise:

- Will access sales increase total margin, not just total revenue?

- How will USPS prevent service degradation during peak weeks?

- What’s the plan if major shipper volumes decline sharply in 2026?

- How will auction pricing reflect true marginal cost by destination?

- What data will USPS publish internally (and possibly externally) to prove this program is working?

If USPS can answer those clearly, this approach could become a template for smart infrastructure monetization across government.

Where this goes next for AI in Transportation & Logistics

Selling access to the last mile is a growth strategy. But it only stays a growth strategy if USPS treats the last mile like what it is: a high-constraint, high-variability system that requires continuous optimization.

For agencies following our AI in Transportation & Logistics series, the practical takeaway is straightforward: AI is most valuable where public obligations and market dynamics collide—service commitments on one side, revenue and efficiency pressure on the other.

If you’re considering a similar move—opening capacity, charging for access, or restructuring service tiers—the next step is to map your data readiness and decision loops. The question worth sitting with is: When demand spikes or budgets tighten, do you have the analytics to steer the system in real time—or are you relying on hope and heroics?