Vision AI fails in production for predictable reasons: data drift, imbalance, bad labels, and leakage. Here’s how energy teams can prevent costly failures.

Why Vision AI Fails in Energy—and How to Fix It

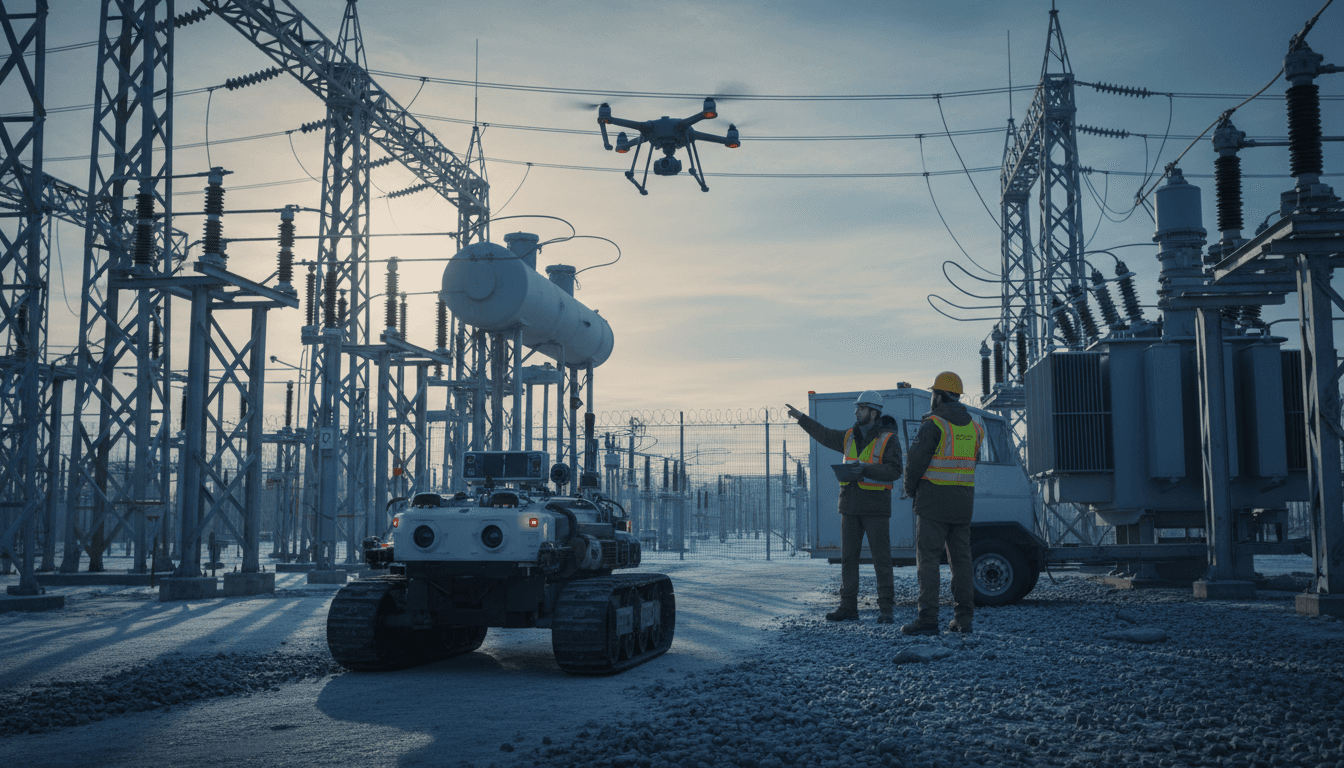

A vision model that’s 95% accurate in a lab can still be the reason a robot arm drops a component, a drone misses a corroded insulator, or a substation camera flags the wrong “intruder” at 2 a.m. Most teams don’t fail because they chose the wrong architecture. They fail because they treat computer vision as a model problem, when it’s usually a data + operations problem.

That gap matters more in energy and utilities than almost anywhere else. Your computer vision system isn’t tagging cute photos—it may be informing predictive maintenance, safety decisions, asset integrity, and even grid reliability when paired with automation.

This post builds on common failure modes documented in industry case studies (including high-profile mishaps in autonomous driving, retail, and manufacturing) and translates them into a practical playbook for AI in robotics & automation teams working in the field: drones, crawlers, inspection robots, fixed cameras, and the software that turns video into decisions.

Vision AI fails because production looks nothing like your dataset

The fastest way to break a vision AI model is to assume the world will keep looking like the images you trained on. In energy environments, the world changes constantly: lighting, weather, seasonal effects, camera angles, dirt on lenses, PPE differences, vegetation growth, and hardware swaps.

A clean training set can create a false sense of confidence. The reality is that production is a moving target.

The most common “looks the same” illusion

Energy inspection is full of subtle shifts that models interpret as meaning:

- A drone camera gets replaced and color response changes

- Winter glare off snow turns “metal surface” into a bright blob

- A thermal camera’s calibration drifts, shifting temperature ranges

- Condensation or dust produces patterns that resemble defects

- Night mode introduces noise that looks like texture

Here’s the line I use internally: your model doesn’t see assets—it sees pixels shaped by your pipeline. If the pipeline changes, so does the meaning.

What to do instead: engineer for drift, not perfection

If you’re deploying vision AI into operational technology environments, plan for drift from day one:

- Freeze and version your imaging pipeline (sensor, lens, compression, preprocessing).

- Track “data health” metrics alongside model metrics (brightness histograms, blur scores, resolution, camera ID, weather tags).

- Alert on distribution changes, not only on prediction errors.

- Keep a rolling “recent production” dataset for evaluation and retraining.

This is where energy teams can learn from demand forecasting: utilities already expect seasonal and behavioral drift. Vision AI needs the same operational mindset.

The four failure modes that show up again and again

Teams tend to discover these the hard way—after a pilot that looked great and a deployment that quietly underperforms.

1) Insufficient data (especially for rare, expensive events)

The most valuable failures in energy are often the rarest: flashover precursors, early-stage corona damage, hairline cracks, partial discharge artifacts, small oil leaks.

If you only have a handful of labeled examples, a model can “memorize” rather than learn. It’ll look impressive during testing and brittle in the field.

Practical fix: treat rare events like a product requirement.

- Define the top 10 “must-detect” defect classes and estimate how many examples you truly have.

- Build a targeted acquisition plan (more patrol routes, synthetic variation, controlled captures).

- Consider active learning: prioritize labeling the frames the model is uncertain about.

2) Class imbalance (the model learns to love ‘normal’)

In inspection, 99% of images are “no defect.” A naive model can get high accuracy by predicting “normal” all the time. That’s not a win—that’s a silent failure.

Practical fix: change what you optimize.

- Use metrics that reflect operational cost: recall on critical defects, false negative rate, precision at a required recall.

- Use stratified sampling and class-aware loss functions.

- Evaluate by asset type and environment (wood pole vs steel tower, coastal vs desert).

A smart grid doesn’t benefit from a model that’s accurate in aggregate. It benefits from a model that’s reliable where risk is highest.

3) Labeling errors (garbage labels, confident model)

Labeling is where many projects quietly lose. For energy assets, labels aren’t just “cat/dog.” You may need domain interpretation: is that discoloration corrosion, staining, or shadow? Is that hotspot load-driven or defect-driven?

Bad labels create false certainty: the model becomes confident about the wrong thing.

Practical fix: build a labeling system like you’d build a safety process.

- Use clear defect definitions and “don’t know” as a valid label.

- Require double review for high-severity classes.

- Track inter-annotator agreement and audit a random sample weekly.

- Store label provenance: who labeled it, when, under what guideline version.

4) Bias and edge cases (the model fails where it matters)

Edge cases are where operational systems get tested: unusual camera angles, uncommon assets, subcontractor PPE variations, night inspections, reflective backgrounds, or non-standard hardware.

Bias in energy vision AI often looks like:

- Better performance on assets from one region than another

- Better performance in daylight than at dusk

- Better performance on newer assets than older, weathered ones

Practical fix: make edge cases a first-class dataset.

- Build “slice” evaluations: performance by region, camera, season, asset family.

- Require minimum performance per slice before deployment.

- Add targeted data collection for weak slices rather than retraining on the full set blindly.

Data leakage: the sneaky reason your pilot looked amazing

Data leakage is when information from the test set bleeds into training, directly or indirectly. It’s common in vision projects because images are highly correlated.

In energy and utilities, leakage often happens when:

- Frames from the same video appear in both train and test

- Images from the same site/day/route get split across datasets

- Augmentations create near-duplicates that land on both sides

The result is a model that “knows the scene,” not the task.

Practical fix: split by asset and time, not by image.

A useful rule: if two images are from the same asset on the same day, they belong in the same split. For inspection robotics, consider splitting by:

- feeder / circuit / substation

- patrol route

- inspection campaign (month/quarter)

This aligns with how the model will face reality: new routes, new days, new conditions.

Evaluation that matches operations (not Kaggle)

If your evaluation doesn’t resemble production, it’s a dashboard decoration.

For AI in robotics & automation, the goal isn’t “high mAP.” The goal is: does the system help a technician make correct decisions faster, with fewer misses?

Build evaluation around decisions

Operational evaluation should answer questions like:

- How many critical defects are missed per 1,000 assets inspected?

- What’s the review workload created by false alarms?

- How often does the system produce low-confidence predictions that require manual review?

- How does performance change at night, in winter, or after camera maintenance?

Use a two-threshold approach (and stop forcing one score)

In practice, I’ve found teams do better with two thresholds:

- A high-confidence threshold that can trigger automation (route flagging, auto-ticket creation)

- A lower threshold that routes items to human review

This design accepts reality: some frames are ambiguous, and pretending otherwise is how you get operational incidents.

Monitoring in production: the part that separates demos from systems

Most model failures aren’t dramatic. They’re slow: performance erodes while everyone’s busy.

Production monitoring for vision AI in energy should include:

- Input drift: camera changes, compression changes, new illumination patterns

- Confidence drift: model becomes more uncertain in certain regions/routes

- Outcome feedback: which alerts were confirmed by humans, which were dismissed

- Latency and uptime: robotics and automation pipelines fail in mundane ways (dropped frames, timeouts, storage limits)

A reliable AI system is one you can observe, not one you can only retrain.

If you’re also running forecasting models for load or renewable generation, you already have the cultural muscle for monitoring and drift response. Apply that same discipline to computer vision.

What this means for smart grids, predictive maintenance, and renewables

Vision AI isn’t a side project anymore. In many utilities, it’s becoming part of the nervous system: drones feeding inspection platforms, robots collecting substation imagery, fixed cameras assisting safety and security, and analytics prioritizing work.

That connects directly to four high-value energy outcomes:

Reliable grid optimization depends on reliable inputs

Grid optimization can’t be smarter than its sensors. If your asset condition signals are noisy or biased, optimization just produces confident mistakes.

Data challenges in vision mirror demand forecasting issues

Both domains suffer from:

- drift over seasons and operations

- underrepresented edge cases

- label/ground truth uncertainty

The difference is that vision has more hidden correlations (location, camera, route), making leakage and bias easier to miss.

Predictive maintenance fails when false negatives feel “rare”

Maintenance leaders care about misses, not averages. A few missed defects can erase the value of hundreds of correct “no issue” predictions.

Renewable integration increases inspection complexity

More distributed assets and more frequent events (storms, heatwaves, vegetation growth) means inspection volume rises. Automation is necessary—but only if your models are production-ready.

A practical checklist for energy vision AI teams (use this next week)

If you’re trying to reduce risk without stalling delivery, this is the shortest path I know.

- Define failure explicitly: list the top defect classes where a miss is unacceptable.

- Split datasets by asset/time to prevent leakage.

- Slice your metrics by region, season, camera, and asset family.

- Audit labels weekly and track disagreement rates.

- Instrument production for drift, confidence, and feedback loops.

- Design a human-in-the-loop workflow with two thresholds.

- Plan targeted data collection for weak slices instead of “more data everywhere.”

Where to go from here

Vision AI models fail for predictable reasons. That’s good news. It means you can prevent most failures before they hit production—if you treat the project as an operational system, not a one-time training run.

If your organization is using computer vision for inspection robotics, substation automation, or safety monitoring, take a hard look at your data pipeline and monitoring first. Model upgrades help, but they’re rarely the bottleneck.

So here’s the real question to carry into 2026 planning: Is your AI system making critical energy decisions without a plan for drift, labeling reality, and edge cases—or have you built the controls that make it trustworthy?