Vine-inspired robotic grippers lift heavy, fragile loads using a sling-like closed loop. See how AI makes them reliable for warehouses and healthcare.

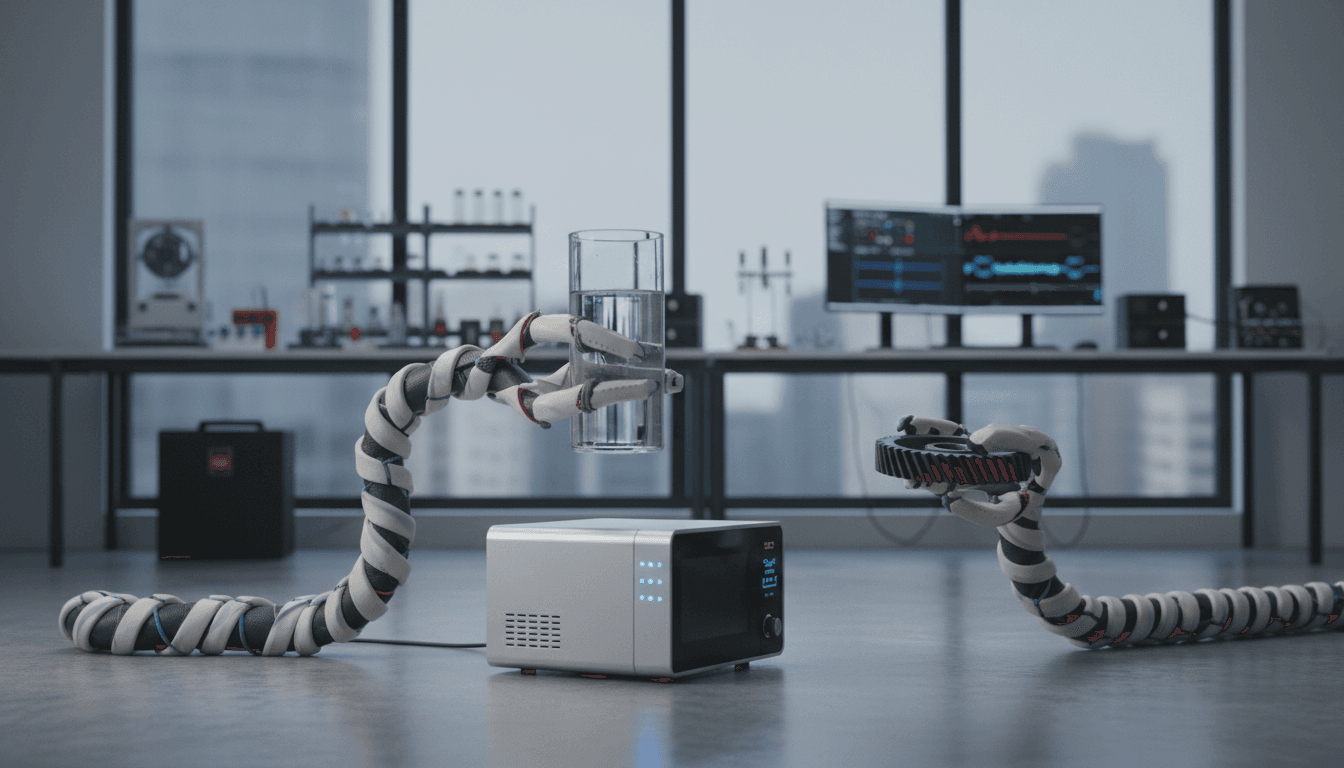

Vine Robots: Gentle Gripping for Heavy, Fragile Loads

A standard two-finger gripper can pick up a metal part all day and still fail on a glass vase. Add weight to the mix—say a kettlebell, a watermelon, or a human body—and the problem gets harder fast: you need high payload capacity without high contact pressure.

That’s why the recent MIT–Stanford work on a vine-inspired robotic gripper is more than a clever soft-robotics demo. It’s a practical answer to a stubborn manipulation gap in AI in Robotics & Automation: handling objects that are both heavy and fragile—reliably, in messy real-world environments.

Here’s what’s different about this “robotic tendril” approach, why it matters to warehouse automation and healthcare robotics right now (December 2025 is peak “move fast” season for logistics), and what you should ask if you’re evaluating soft robotic grippers for a pilot.

The real bottleneck: force without damage

Robotic manipulation fails most often at the interface between tool and object. Vision can be great. Path planning can be great. But if your end effector concentrates force into a small area, you’ll crush the item, slip it, or both.

Traditional grippers typically rely on one of two strategies:

- Pinch and clamp (rigid fingers, parallel jaw, servo grippers): strong and fast, but sensitive to object geometry and surface friction.

- Vacuum suction: great for flat, non-porous surfaces; unreliable for textured, dusty, wet, perforated, or irregular items.

Soft robotic grippers improved the picture by distributing contact, but many still behave like “soft fingers”: they wrap partially, apply force locally, and can struggle when the object is heavy, oddly shaped, or buried in clutter.

The point of the vine-inspired design is simple: create a grasp that behaves more like a sling than a pinch. Sling grasps scale better with weight because the load is carried across a larger contact area.

Snippet-worthy: The easiest way to lift a fragile heavy object is to stop pinching it and start suspending it.

What MIT and Stanford built—and why the “closed loop” matters

Answer first: The MIT–Stanford gripper works because it transforms from an open-loop vine (for reaching and wrapping) into a closed-loop sling (for secure lifting).

The system starts from a pressurized box near the target. From that box, long flexible tubes inflate and “grow” outward—like a sock turning inside out. As they extend, they twist and coil around the object. Then they continue growing back toward the box, where they’re clamped and mechanically wound to lift.

Open-loop vs. closed-loop in plain terms

Most vine robots are open-loop: they extend like a line or tentacle. They’re great for reaching through clutter, but they don’t naturally form a secure grasp that can be retracted while maintaining stability.

This design adds the missing ingredient: loop closure.

- Open-loop phase: reach, position, wrap, and “thread” through the environment.

- Closed-loop phase: attach back to the base so the robot becomes a continuous loop.

- Retract phase: winch the loop to lift the payload with distributed support.

That sequencing is a big deal for automation because it matches how many real tasks happen:

- Find and approach the object (often in clutter).

- Establish safe contact.

- Secure the object.

- Move it without shifting or dropping.

Most systems optimize step 4 and struggle at step 2.

A quick picture of what it can lift

In demonstrations, the smaller arm-mounted version lifted both fragile and heavy items: a glass vase, a watermelon, a kettlebell, and metal rods. The larger setup was designed around patient transfer—supporting a human body by gently winding the vines into a sling.

This isn’t “soft for softness’ sake.” It’s a mechanical strategy that makes the object’s fragility less relevant because the load is spread out.

Where AI fits: making soft grippers dependable, not just impressive

Answer first: Soft hardware becomes commercially useful when AI turns it into a controlled, measurable process—contact, tension, slip risk, and trajectory become variables you can manage.

The RSS article focuses on the mechanical breakthrough (rightly). But to deploy a vine-inspired robotic gripper in the field, teams still need robust autonomy and monitoring. AI is the layer that makes that possible.

1) Perception: choosing where to “thread the vine”

A vine robot can push through clutter, but it still needs to decide:

- Where are the safe wrap paths?

- What regions are fragile (stems, handles, protrusions)?

- Is the target partially occluded?

In warehouses, this is classic bin picking with a new twist: instead of planning finger contact points, you plan wrap paths and closure points.

Practical AI methods that map well here:

- Instance segmentation to isolate the target in clutter.

- Grasp affordance prediction reinterpreted as “wrap affordance.”

- 3D scene reconstruction to estimate whether the vine can pass behind/under the object.

2) Control: regulating pressure, tension, and lift

These robots are pneumatic and compliant. That’s a strength, but it introduces variability: material stretch, pressure lag, friction, and object movement.

AI can help by learning control policies that keep the lift stable:

- Use tension feedback (from winch torque/current) as a proxy for load distribution.

- Detect incipient slip from small changes in tension dynamics.

- Modulate growth pressure so the vine slides under a patient or product without creating pressure points.

If you’ve ever tuned a conventional gripper for mixed SKUs, you know why this matters. A soft gripper that can’t self-monitor becomes a liability in production.

3) Safety and compliance: proving it’s gentle

Healthcare robotics raises the bar. For patient transfer, you need clear constraints:

- Maximum safe contact pressure

- Redundant fail-safes

- Predictable behavior during emergency stop

AI adds value when it supports measurable safety, not vibes. The systems that win will be the ones that can report, in real time:

- how much load is being carried,

- where the load is concentrated,

- whether the wrap is symmetric,

- and whether retraction is stable.

Use cases that actually pencil out (and why December matters)

Answer first: The best early deployments are places where damage, variability, or labor strain is expensive—and where “sling-like” handling beats pinch grasping.

Warehouses and parcel operations: peak season pain is real

Late Q4 and early Q1 are when logistics operators feel every weakness in automation: oversized items, odd packaging, returns, fragile gifts, mixed pallets. A vine-inspired gripper is attractive because it can handle variation without a custom tool for every SKU.

Where it fits first:

- Exception handling cells (damaged packaging, irregular shapes)

- Returns sorting (unknown geometry, mixed materials)

- Depalletizing mixed loads where suction fails

The contrarian take: don’t aim this at your fastest pick line first. Put it where humans currently handle the “annoying” items that break automation assumptions.

Healthcare robotics: patient transfer without caregiver back injuries

Patient transfer is one of the most physically taxing caregiver tasks. The vine concept targets a real operational problem: caregivers often must reposition a patient onto a sling before a mechanical lift can help.

A vine robot that can snake under and form its own sling reduces that manual step. If you’ve worked with hospitals, you know the value isn’t only labor savings. It’s:

- reduced injury risk,

- improved patient comfort,

- more consistent transfers across staff experience levels.

This is also a domain where gentleness is the product. Soft robotics isn’t a nice-to-have.

Ports and heavy industry: “soft” doesn’t mean “light duty”

The article hints at cranes and cargo. That’s plausible, but the near-term opportunity is narrower: hybrid handling where surfaces are inconsistent and damage costs are high.

Think:

- coated parts that scratch easily,

- bundled items with unpredictable contact points,

- objects that must be stabilized during motion.

A sling-style grasp can reduce micro-damage that rigid tooling causes (scrapes, dents, pressure marks)—the kind of defects that quietly kill yield.

If you’re evaluating soft robotic grippers, ask these questions

Answer first: Don’t evaluate a vine-inspired gripper like a two-finger gripper. Evaluate it like a lifting system: stability, monitoring, failure modes, and cycle time.

Here’s a short checklist I’d use in a pilot discussion.

Performance and throughput

- What’s the cycle time end-to-end (reach → wrap → close → retract → place)?

- What’s the payload range with safety margin (not just “max payload”)?

- How does performance change across object stiffness and surface friction?

Sensing and control readiness

- What sensors infer tension, load, and slip? (Winch current can be useful, but redundancy matters.)

- Is there a method to validate a “good wrap” before lifting?

- How is pressure regulated, and how quickly can it respond?

Reliability and maintenance

- What’s the wear profile of the inflatable tubes?

- How does the system behave with dust, oils, and temperature swings?

- Is replacement modular, and what’s the maintenance interval?

Safety and failure modes

- If power fails mid-lift, what happens?

- If a tube punctures, what’s the controlled fallback?

- In healthcare, how is contact pressure limited and audited?

Practical stance: If a vendor can’t explain failure modes clearly, the demo doesn’t matter.

What this signals for the AI in Robotics & Automation roadmap

Answer first: Nature-inspired mechanisms are widening the “grasping toolbox,” and AI will decide which tool to use, when, and how aggressively.

The past few years have seen a wave of interest in humanoids, but manipulation progress often comes from less flashy places: specialized end effectors, better compliance, and better sensing.

Vine-inspired grippers expand the design space because they combine:

- Reach-through-clutter behavior (like a tentacle)

- Closed-loop security (like a sling)

- Soft contact (like a conformal wrap)

That combination lines up with where automation needs to go next: fewer curated environments, more real variability.

The next step is obvious and exciting: AI-driven grasp strategy selection. A robot should decide, per object and per scene:

- suction vs. pinch vs. wrap,

- partial wrap vs. full loop closure,

- how much tension is acceptable given fragility.

When that decision-making becomes robust, you get systems that can handle a coffee cup and a car part with the same arm—without swapping hardware every hour.

Most companies get this wrong by treating soft grippers as a novelty. The better view is simpler: soft grasping is an engineering response to uncertainty, and AI is how you control it.

If you’re building or buying automation in 2026, the question to ask isn’t “Can it lift a vase?” It’s: Can it prove it lifted the vase safely—every time—at scale?