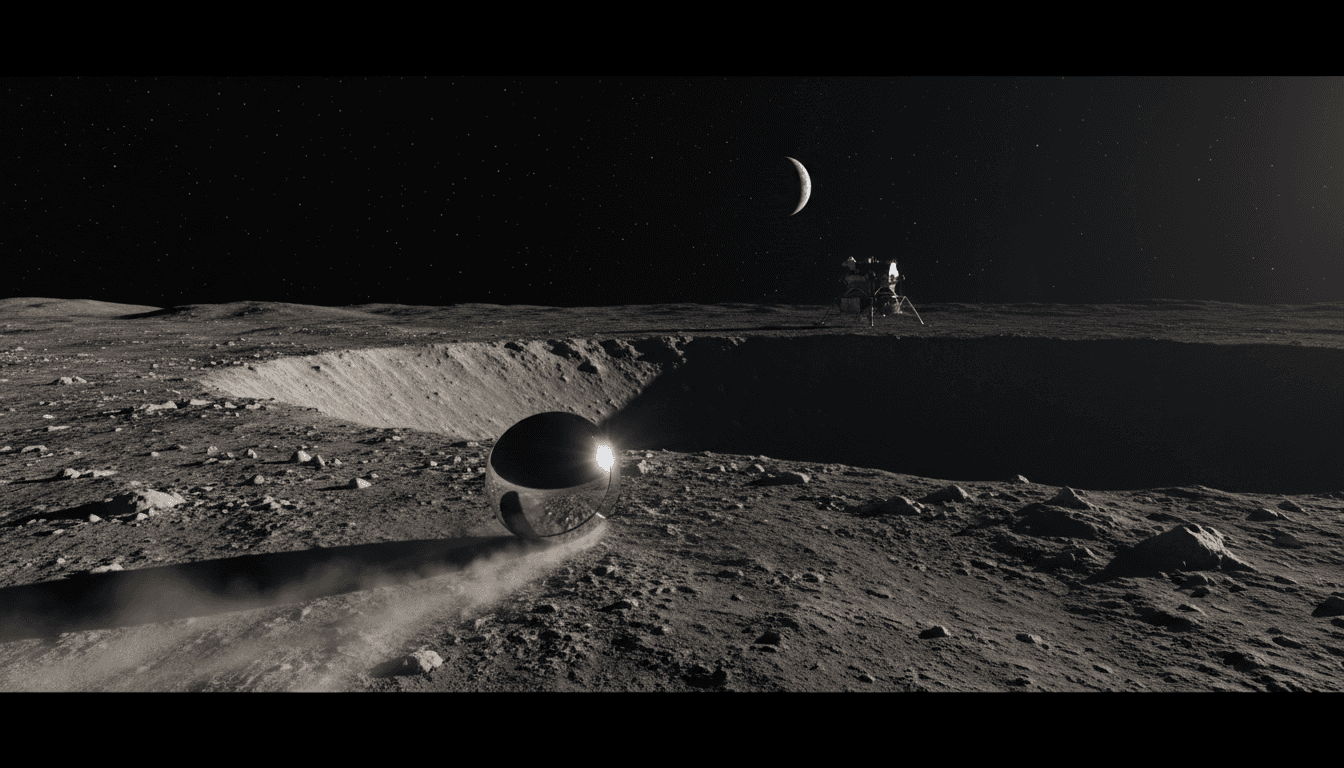

Spherical robots like RoboBall may handle lunar terrain better than rovers. See how AI autonomy makes rolling exploration practical in extreme environments.

Why Spherical Robots May Win on Lunar Terrain

Rolling a robot across the Moon sounds almost too simple—until you remember what “terrain” means up there: steep crater walls, loose regolith that behaves like powdery snow, sharp rocks, and long stretches with no friendly GPS to bail you out. Most companies still default to the same mobility playbook—wheels, tracks, legs—then spend years hardening those systems against the environment.

Texas A&M’s team, led by roboticist Robert Ambrose, is pushing a cleaner idea: a spherical robot (“RoboBall”) that can literally roll across rough terrain. The geometry is the point. A ball doesn’t have a “front bumper” to snag. It doesn’t need to steer like a car. And because the shell can protect delicate internals, you can think differently about autonomy, payloads, and survivability.

This post is part of our “AI in Robotics & Automation” series, and I’m going to take a stance: the shape is interesting, but the real story is the autonomy stack. A spherical robot becomes valuable when AI can (1) decide where to go with limited information, (2) control motion on unpredictable surfaces, and (3) keep itself safe without constant human babysitting.

Why lunar mobility keeps failing (and why a ball helps)

Answer first: Lunar robots get stuck because the Moon punishes traction, visibility, and recovery. A spherical form factor reduces snag points, spreads impacts, and can simplify mechanical recovery behaviors.

Traditional rovers have done incredible work, but the Moon’s surface creates a nasty three-part problem:

- Traction is unreliable. Regolith can behave like talcum powder. Wheels slip, dig, and trench—especially when climbing or turning.

- Obstacles are deceptive. Low sun angles create harsh shadows. Rocks look like pits. Pits look like rocks. Your perception system has to be cautious, which slows everything down.

- Recovery is expensive. A rover that high-centers or wedges a wheel can end a mission. In remote operations, “send a technician” isn’t a thing.

A spherical robot changes the failure modes:

- No high-centering in the usual sense. There’s no chassis belly to hang up.

- Impacts distribute around a shell. That can protect sensors/computing mounted internally.

- Self-righting is built in. A sphere doesn’t care which side is “up”—useful when bouncing, tumbling, or rolling down a slope.

Here’s the non-obvious advantage: a ball’s mechanical simplicity buys you autonomy budget. Fewer actuators and joints can mean fewer failure points—and more engineering time for navigation, mapping, and mission logic.

RoboBall’s real differentiator: AI autonomy in low-information environments

Answer first: A spherical explorer only works at lunar scale if it can navigate with sparse sensing, delay-tolerant communications, and robust slip-aware control—classic AI robotics territory.

On the Moon, autonomy isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s a requirement because:

- Communications are delayed and intermittent. Even small latencies make “joystick driving” inefficient; occlusions and line-of-sight issues make it worse.

- Lighting conditions are brutal. The Moon’s lack of atmosphere means sharp contrast and long shadows.

- Terrain interaction is uncertain. Wheel slip is hard; controlled rolling and controlled slipping are also hard.

Perception: seeing a safe path when shadows lie

For a rolling robot, perception needs to answer a very practical question: “If I roll there, will I get trapped, damaged, or lose control?” That’s not just obstacle detection—it’s terrain understanding.

A realistic autonomy pipeline for a RoboBall-style system often combines:

- Visual-inertial odometry (VIO): Fusing cameras with IMU data to estimate motion when wheel odometry is meaningless.

- Terrain classification: Learning-based models that label surfaces as high-risk (soft regolith, steep slopes, rock fields) vs low-risk.

- Uncertainty-aware mapping: Maintaining a costmap that tracks confidence, not just “free vs occupied.”

Snippet-worthy truth: On the Moon, the robot that admits uncertainty survives longer than the robot that acts confident.

Planning: choosing routes that a sphere can actually execute

A ball can go places a rigid rover shouldn’t—but it can also roll into trouble quickly. Path planning has to consider dynamics, not just geometry.

Instead of asking “Is there space?”, planners ask:

- What’s the estimated slope angle and slope change?

- How likely is loss of control if we accelerate downhill?

- Can we stop if the surface is softer than expected?

That’s where AI-driven planners shine. They can:

- Predict slip from recent motion + sensor cues

- Select conservative trajectories when uncertainty spikes

- Re-plan continuously as the map updates

Control: turning rolling into “driving”

The control problem is where spherical robots earn their keep—or fail fast. A ball’s actuators (often internal mechanisms that shift mass or drive an internal wheel) must manage:

- Directional control without traditional steering

- Speed modulation on slopes

- Stability when the terrain causes bouncing or micro-slips

A practical approach is hybrid:

- Classical control for stability constraints

- Learning-based adaptation for friction/slip changes

If you care about AI in robotics & automation, this is a familiar pattern: physics-based safety rails + learning for the parts you can’t model well.

What spherical robots can do that rovers can’t (and what they’re bad at)

Answer first: Spherical robots excel at survivable traversal and simple recovery, but they trade away payload volume, sensor placement stability, and precise manipulation.

Let’s be honest: a RoboBall isn’t a drop-in replacement for a six-wheeled rover with a mast camera and an arm. It’s a different tool.

Where a RoboBall-style design shines

- Crater exploration and steep approaches: Rolling and self-righting can handle tumbling events that would end a traditional rover.

- Distributed scouting: A mission could deploy multiple spheres as inexpensive scouts that map risk, then route a larger rover.

- High reliability from fewer moving parts: Mechanical simplicity can translate into longer operational life—if dust sealing and thermal design are done right.

A strong mission concept is “sphere scouts + specialist robots.” Let the spheres map the unknowns and identify safe corridors.

Where the spherical form struggles

- Sensor stabilization: A rolling shell makes it harder to keep cameras and antennas pointed. You can gimbal internally, but that adds complexity.

- Precise sampling/manipulation: A ball is not a great platform for digging, drilling, or placing instruments.

- Energy and thermal constraints: The Moon’s two-week day/night cycle stresses batteries and thermal systems. A sphere’s surface area and insulation choices become critical.

Good engineering is about trade-offs. I like the RoboBall direction because it’s honest about its purpose: mobility first, exploration second—and it uses AI to close that gap.

From the Moon to the factory floor: why this matters for automation teams

Answer first: Extreme-environment autonomy creates robust techniques you can reuse in warehouses, mines, ports, and inspection robotics—especially slip-aware navigation and uncertainty-driven planning.

People hear “lunar robot” and think it’s purely space-tech. It isn’t. The autonomy lessons translate directly to terrestrial automation.

Transferable AI robotics capabilities

- Navigation without GPS: Useful in warehouses, tunnels, and metal-heavy facilities where localization drifts.

- Terrain and floor-condition awareness: Wet floors, loose gravel, oil spots—industrial AMRs fail on the same physics problems as lunar rovers.

- Resilience-first design: Robots that keep operating when sensors degrade, lighting changes, or maps are wrong.

Here’s what I’ve found in real deployments: most autonomy failures are “boring” edge cases—glare, dust, floor reflectivity, unexpected ramps. Building for the Moon forces you to treat those as first-class requirements.

A practical blueprint for teams building autonomous mobile robots

If you’re leading an AI in robotics & automation project, steal these principles:

- Treat traction as a sensor. Use IMU + motor current + visual motion to estimate slip continuously.

- Plan with uncertainty, not hope. If the map is low-confidence, the robot should slow down and gather better data.

- Design recovery behaviors early. A robot that can self-recover saves support labor and reduces downtime.

- Separate “can move” from “should move.” Mobility without mission logic becomes a liability.

That’s the same logic behind a RoboBall: a robot that’s hard to strand is a robot you can trust to operate farther from help.

“People also ask” about spherical robots for lunar exploration

Answer first: The most common questions are about control, sensing, and mission fit—because spherical robots don’t match our intuition about rovers.

Can a spherical robot steer accurately?

Yes, if the internal drive system can create controlled torque and the autonomy stack closes the loop with IMU + vision. Accuracy won’t look like a slow rover crawl; it will look like short controlled rolls and frequent corrections.

How does a rolling robot keep its sensors pointed?

Typically through internal stabilized sensor modules (gimbals) and clever behavior design—stop-and-scan, roll-and-scan, and periodic orientation resets.

Is a ball safer around rocks and drops?

It can be, because impacts distribute across a shell and the robot can self-right. But it also needs strict hazard detection because once it commits downhill, stopping distance matters.

Why not just use legs?

Legs can be excellent, but they’re mechanically complex, power-hungry, and harder to harden for dust and thermal extremes. For scouting and traversal, simplicity often wins.

Where RoboBall fits in the future of lunar missions

Answer first: Spherical robots are most valuable as autonomous scouts that extend reach into risky terrain, reduce mission risk for larger assets, and generate high-quality maps for follow-on operations.

The Moon is busy in late 2025: national programs and commercial players are planning more frequent landers, more surface experiments, and longer-duration operations. That cadence changes what “good robot design” means. It’s not just about one heroic rover. It’s about repeatable missions with predictable costs.

A RoboBall-style platform fits that shift. It’s the kind of robot you can deploy in numbers, accept some loss, and still win—because the autonomy improves across missions.

If you’re evaluating AI-powered robotics for remote or hazardous environments (space, mining, offshore, security patrols), the question to ask isn’t “Should we build a sphere?” It’s this:

Are we designing autonomy that assumes the world will be messy—or are we pretending it’ll behave like a lab?

If you want leads from this series to be useful, here’s a solid next step: map your own environment’s “lunar equivalents” (slip, shadows, comms gaps, recovery cost) and audit whether your autonomy stack has explicit answers for each. That’s where reliability—and ROI—comes from.