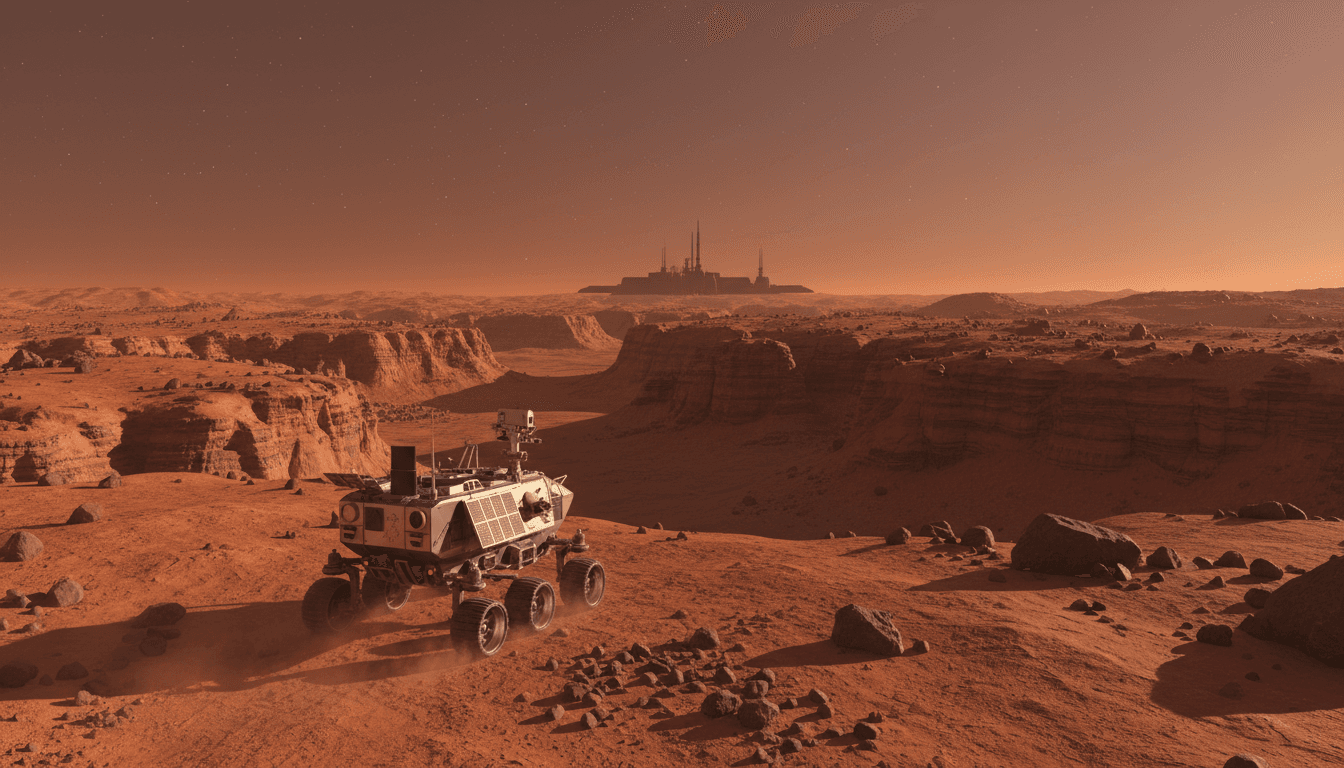

Space robot autonomy is a blueprint for industrial AI. Learn what planetary rovers teach about reliability, recovery, and safe autonomy in automation.

Space Robot Autonomy Lessons for Earth Automation Teams

NASA doesn’t drive a rover the way you drive a forklift. The signal delay alone makes that impossible: when Mars and Earth are far apart, a command can take over 20 minutes one-way to arrive. That single constraint forces a design mindset most factories and warehouses still haven’t adopted: robots must make good decisions without waiting for you.

That’s why I liked Robot Talk Episode 127, where Claire spoke with Frances Zhu (Colorado School of Mines) about intelligent robotic systems for space exploration. Space is a harsh teacher—limited power, uncertain terrain, minimal sensing, and no “send a technician” option. The upside is that the autonomy patterns that survive on other planets tend to be exactly what Earth-based automation needs next.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and I’m going to treat this episode as a practical case study: what space robotics gets right about AI-driven autonomy, and how to translate those lessons into manufacturing, logistics, and field service robotics.

Planetary exploration forces real autonomy (and that’s the point)

Space robotics makes one idea unavoidable: autonomy isn’t a feature; it’s an operating requirement. When your robot can’t be teleoperated in real time, “smart enough” becomes a measurable threshold, not marketing.

Frances Zhu’s background—mechanical and aerospace engineering, a Cornell Ph.D. in aerospace, NASA fellowship work, and research spanning machine learning, dynamics, systems, and controls—sits right at the intersection that matters: AI can propose actions, but physics decides whether they’re safe and feasible.

Here’s the translation for Earth-based automation teams: if your current deployment depends on constant human babysitting, you don’t have autonomy—you have remote control with extra steps. Planetary robotics pushes us toward systems that:

- Perceive messy environments (dust, low contrast, occlusions)

- Estimate state when sensors lie or drop out

- Plan paths and actions under uncertainty

- Recover from slips, sinkage, and unexpected obstacles

- Operate within hard constraints (power, compute, comms, safety)

If that sounds like a Mars rover, it also sounds like an autonomous mobile robot (AMR) in a congested warehouse, or an inspection robot in a chemical plant.

The autonomy stack that survives off-Earth

The most durable architecture I’ve seen in both space and industry is layered autonomy:

- Reactive safety layer (don’t crash, don’t tip, don’t exceed loads)

- Local planning (short-horizon navigation and foothold/traction choices)

- Mission planning (which goals to pursue, in what order)

- Human intent layer (operators specify outcomes and constraints, not joystick commands)

Space teams do this because they must. Industrial teams should do it because it scales.

Extreme environments make uncertainty the default

A clean demo environment is the exception. The reality? Your robot will face conditions you didn’t label, didn’t simulate, and didn’t anticipate.

Planetary surfaces are the ultimate “domain shift” problem: lighting changes, dust changes the friction, slopes hide hazards, and terrain isn’t repeatable. That pressure shapes a core principle:

Robust autonomy is less about perfect perception and more about reliable decision-making under uncertainty.

For manufacturing and logistics, “uncertainty” often looks less dramatic but is just as operationally expensive:

- Pallets placed a few inches off standard

- Reflective shrink wrap confusing depth cameras

- Seasonal congestion (yes, December peaks are real)

- Floor wear changing traction across aisles

- People stepping into robot routes at the worst moment

What works: planning with constraints, not wishful thinking

Space robotics tends to be strict about constraints because failures are expensive and unrecoverable. That mindset transfers well:

- Energy is a first-class variable. On a rover, energy budgeting is life-or-death. In a warehouse, energy planning determines whether robots die mid-shift or finish their route sets.

- Traction and stability are modeled, not assumed. Rovers reason about slopes and sinkage. Industrial AMRs should explicitly reason about floor conditions, incline transitions, and load-induced stability margins.

- Fallback behavior is designed upfront. A rover that gets confused doesn’t “keep going.” It stops, re-localizes, or returns to a safe pose. Many industrial robots still lack disciplined “safe degraded modes.”

If you’re building AI-driven robotics for production, this is the stance to take: define the failure modes you’ll tolerate, then engineer the robot to stay inside that envelope.

AI in space robots: it’s not about flashy models

The internet loves the idea of a rover “thinking like a human.” Real autonomy is more practical.

In space robotics, AI earns its keep in a few specific jobs:

1) Navigation in terrain you can’t map ahead of time

A rover can’t rely on prebuilt maps. It needs onboard perception and local planning to pick traversable routes. On Earth, the analog is an AMR encountering:

- Temporary blockages (holiday overflow, construction)

- Dynamic obstacles (people, carts)

- Unmapped changes (new racks, moved stations)

The lesson: local autonomy beats global perfection. Focus investment on reliable short-horizon decisions, then let mission planning stitch those decisions into productivity.

2) State estimation when sensors are imperfect

Space sensors drift. Dust and lighting interfere. Wheel slip breaks odometry. So you fuse signals and keep uncertainty estimates honest.

Industrial teams should copy that discipline. If your system treats localization as “a number” instead of “a distribution,” you’ll eventually ship robots that look confident while being wrong.

3) Intelligent task execution, not just movement

Exploration robots aren’t only trying to move; they’re trying to do science: approach targets, place instruments, collect samples, and prioritize objectives.

That’s the closest bridge to service robotics and advanced automation: the value is in deciding what to do next, not merely moving safely.

A practical industrial parallel:

- In a fulfillment center, the robot should decide whether to reroute, wait, or re-sequence picks when congestion spikes.

- In inspection, the robot should decide whether an anomaly merits a closer pass, different sensor angle, or escalation.

That’s where AI-driven autonomy becomes a business tool rather than a lab demo.

Space-to-industry transfer: 5 lessons you can use next quarter

Most companies get this wrong: they shop for “more AI” when they actually need better system design. Space robotics is a strong template because it forces design clarity.

1) Treat comms as unreliable—even when you have Wi‑Fi

Space assumes delays and dropouts. Earth deployments should too.

Actionable move: design behaviors for “no network” operation:

- Local mission buffering

- Safe stop states

- Store-and-forward logs

- Onboard health checks

If you’re deploying robots across multiple facilities, this alone reduces operator burden.

2) Use simulation for coverage, then test for truth

Space programs use simulation heavily because you can’t try things on Mars first. But they also respect that simulation lies.

Actionable move: measure sim-to-real gaps explicitly:

- Track which failure classes appear only in real environments

- Add targeted “nasty tests” (glare, dust, occlusion, wheel slip)

- Maintain a regression suite of real-world incident replays

3) Make autonomy explainable to operators

When a rover does something odd, the team needs to understand why it happened. Industrial autonomy needs the same transparency to earn trust.

Actionable move: implement operator-facing “reason codes,” such as:

- “Stopped: localization uncertainty exceeded threshold”

- “Rerouted: aisle congestion above limit”

- “Reduced speed: traction risk detected”

This is explainable AI in robotics in its most useful form: not a philosophical debate, but a practical debugging tool.

4) Engineer for recovery, not perfection

Space robots are designed to get unstuck, re-localize, and continue. Many industrial systems still treat incidents as “call a human.”

Actionable move: invest in three recovery primitives:

- Backtrack to last known safe pose

- Re-localize using multiple cues (fiducials, geometry, semantic landmarks)

- Escalate with context (video + map snippet + last actions)

Incident recovery is where autonomy pays for itself.

5) Keep learning pipelines separate from safety pipelines

This is a big one. You can use machine learning to improve perception and decision-making, but safety constraints must remain enforceable and testable.

Actionable move: structure autonomy so that learning components propose actions, while a deterministic safety layer validates them against constraints (speed limits, stop distances, stability margins, geofences).

That architecture is common in high-stakes robotics because it’s auditable—and because it prevents “clever” behavior from becoming dangerous behavior.

People also ask: what does planetary robotics mean for my automation roadmap?

Is space robotics relevant if I’m not building rovers?

Yes—because the hard parts are the same: uncertain environments, limited sensing, tight power/computation budgets, and the need for safe autonomy. A hospital corridor, a mine, and a messy warehouse are “planetary” in all the ways that matter to a robot.

Does AI replace classical controls in autonomous robots?

No. The strongest systems combine both. Machine learning helps with perception and messy pattern recognition. Controls and dynamics keep the robot stable, efficient, and safe. Frances Zhu’s focus across ML and controls is a good reminder that hybrid intelligence is the practical path.

What’s the fastest way to improve autonomy outcomes?

Define your operational envelope (terrain, loads, lighting, congestion), instrument failures, and build recovery behaviors. You’ll get more ROI from failure engineering than from swapping model architectures every quarter.

Where this fits in the “AI in Robotics & Automation” series

The bigger theme of this series is simple: AI enables robots to act with judgment, not just repeat motions. Space exploration is a stress test for that idea. If autonomy can work where help is minutes to hours away and conditions are unforgiving, it can work in your facility—assuming you design it with the same seriousness.

If you’re planning your 2026 automation roadmap right now (and many teams are, given December budgeting cycles), take a page from planetary robotics: prioritize autonomy that reduces human babysitting, handles uncertainty, and recovers cleanly. The robots that win won’t be the ones with the fanciest demos. They’ll be the ones that keep working on a bad day.

Want a useful thought exercise for your next planning meeting? If your robot lost network for 30 minutes during peak operations, would it stay safe, stay productive, and tell you exactly what it did? If the answer is “no,” you’ve got a clear, high-ROI autonomy backlog.