Robot metabolism enables modular robots to self-repair and reconfigure by sharing parts. See what it means for AI-driven automation in factories and logistics.

Self-Repairing Modular Robots: What “Robot Metabolism” Means

A factory robot going down doesn’t just pause a line. It triggers a chain reaction: missed ship windows, overtime, expedited freight, angry customers, and a maintenance backlog that never quite clears.

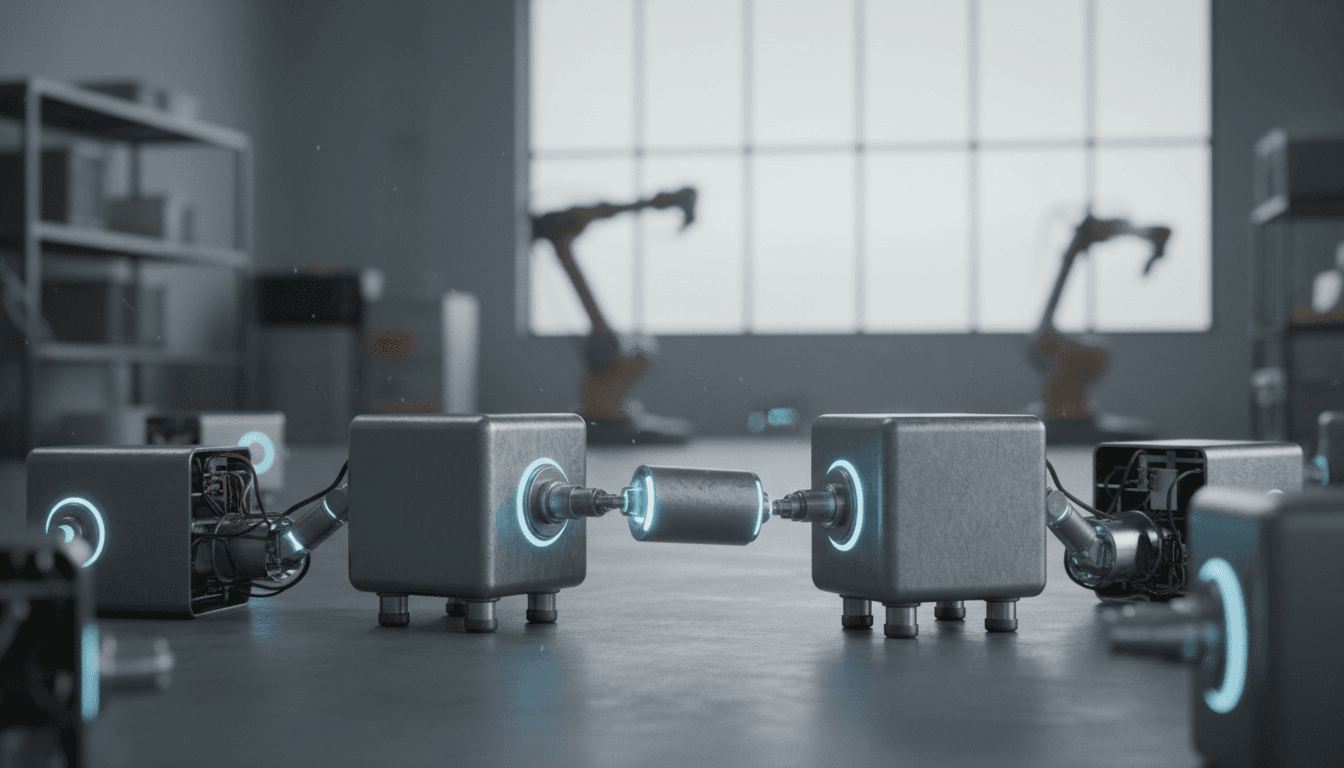

Now picture a different failure mode. A robot detects a damaged joint, rolls over to a “parts buddy,” borrows a working module, snaps it into place with magnets, and gets back to work—while the donor robot reconfigures itself to stay useful. That’s the core idea behind what some engineers are calling robot metabolism: robots that grow, self-repair, and morph by absorbing parts from other robots, and can help their neighbors do the same.

This matters for the “AI in Robotics & Automation” series because adaptation is the missing link between impressive demos and reliable, scalable automation. Hardware modularity enables the physical change; AI enables the decision-making: when to reconfigure, what to borrow, how to keep throughput stable, and how to do it safely.

Robot metabolism, explained without the hype

Robot metabolism is the ability for a robot to change its body using available modules—often from other robots—to maintain or expand capability. Think of it as physical reconfiguration plus repair, driven by local constraints.

In the RSS summary, the key ingredients are clear:

- Modular bodies: robots are built from repeated functional blocks (actuators, joints, wheels, grippers, sensors, power).

- Magnetic coupling: modules attach/detach quickly, creating a mechanical “plug-and-play” layer.

- Shared parts: robots can absorb modules from other robots.

- Assisted adaptation: robots can help others reconfigure, not just themselves.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: the headline isn’t “robots that eat other robots.” The real shift is that maintenance becomes a fleet-level optimization problem, not a single-machine problem. And that’s exactly the kind of problem AI is good at.

Why magnets and modularity are suddenly practical

Magnetic connectors aren’t new. What’s changing is the ecosystem around them:

- Better on-board perception and localization for tight alignment

- Higher-torque compact actuators for modules that can actually carry load

- Improved battery density and power electronics that fit in smaller form factors

- Faster, cheaper embedded compute for local control loops

Modular robotics used to struggle with a brutal tradeoff: modular systems were flexible, but weaker and more complex than purpose-built machines. The metabolic approach tries to claw back reliability by making “replacement” a native behavior, not a human intervention.

The AI layer: from “self-repair” to autonomous fleet resilience

Modular hardware enables reconfiguration; AI decides what reconfiguration is worth doing. Without AI, a robot that can detach its arm is still just a robot with a party trick.

To make robot metabolism useful in manufacturing, healthcare, or logistics, the system needs AI across four levels:

1) Fault detection that’s actionable

The goal isn’t detecting that something is wrong—it’s diagnosing what module swap fixes it. Practical approaches combine:

- Motor current signatures (early indicator of joint wear)

- Vibration patterns (bearing issues)

- Thermal drift (overheating in drivers)

- Vision-based self-inspection (cable snag, physical damage)

A “metabolic” robot should output a clear action: swap Module B3 (elbow) with any compatible B-series elbow module within 15 meters.

2) Reconfiguration planning under constraints

Once a fault is detected, AI has to solve a constrained planning problem:

- Which modules are available nearby?

- What’s the quickest safe configuration change?

- Will borrowing a module reduce overall fleet throughput?

- What tasks can each robot still perform after the swap?

This is where multi-agent planning and resource allocation show up. You’re no longer optimizing a single robot’s uptime; you’re optimizing the fleet’s ability to hit production or SLA targets.

3) Skill transfer across morphologies

A robot that changes shape can’t rely on a single static controller. It needs policies that generalize.

In practice, that means:

- Parameterizable control policies (controllers conditioned on module graph / kinematics)

- Fast calibration routines after a swap (pose offsets, torque limits)

- “Good enough” manipulation behavior that works across slightly different arms

If your automation team has been burned by brittle robot programs, this is the opposite direction: software that expects the body to change.

4) Collaboration protocols (“who gives up a part?”)

The most interesting line in the RSS summary is that these robots can help their “brethren” adapt too.

That implies negotiation or policy rules such as:

- A robot with slack capacity becomes a donor.

- Donors can loan modules temporarily based on priority.

- The system maintains a minimum viable capability for each zone.

A fleet that can trade parts is a fleet that can trade uptime.

Where this hits first: three high-value use cases

Robot metabolism will matter most where downtime is expensive and the environment changes faster than maintenance cycles. Here are the applications I’d bet on.

Manufacturing: maintenance becomes a scheduling problem

Factories already treat humans and machines as schedulable resources, but robot maintenance is still too manual. Metabolic modular robots turn failures into rescheduling events:

- A robot flags “joint degradation” during a planned micro-stop.

- A nearby robot lends a joint module.

- The damaged module goes to a recharge-and-test station.

- The fleet rebalances tasks to keep the line moving.

The operational win isn’t perfection—it’s predictable continuity. For high-mix production (common in 2025), flexible automation matters more than raw cycle time.

Practical example: end-of-year throughput pressure

December is when many operations teams feel the squeeze: order backlogs, staffing constraints, and shipping cutoffs. In that context, self-repairing modular robotics isn’t a novelty. It’s a way to keep automation from becoming your bottleneck when maintenance can’t keep up.

Logistics: adaptive robots that match the day’s demand

Warehouse workloads swing hourly. Most robotic fleets are either:

- Overbuilt for peak (expensive), or

- Sized for average (misses SLAs on spikes)

Metabolic modular robots point to a third option: robots that reconfigure to fit demand.

- During picking peaks: more gripper modules, more reach

- During replenishment: more mobility modules, higher payload

- When congestion rises: smaller footprint morphologies to navigate dense aisles

Even a modest capability to “borrow” a mobility base or add a stabilizer module changes what you can automate without buying a whole second fleet.

Healthcare and service: safer operation through graceful degradation

Healthcare robotics has a different priority order: safety, reliability, and predictability beat speed.

A metabolic service robot could:

- Detect sensor failure and swap a sensor module before entering patient areas

- Reduce its degrees of freedom if a joint is compromised (safer motion)

- Request assistance from another robot for module transfer rather than asking staff

This is a big deal because hospitals don’t have the luxury of frequent robot downtime or specialized on-site robotics technicians.

What needs to be true for robot metabolism to work in the real world

The promise is real, but only if the engineering details are handled brutally well. Here’s what usually breaks these concepts when they leave the lab.

Standardized modules and “robot USB-C” interfaces

Modularity only scales with standardization:

- Mechanical interface (alignment, load rating, latch redundancy)

- Power interface (voltage levels, current limits, hot-swap behavior)

- Data interface (latency guarantees, device identity, versioning)

If every module is bespoke, your “self-repair” is just moving complexity from the maintenance team into the design team.

Verification, safety, and lockout behaviors

A robot that can reconfigure itself must prove it’s safe after reconfiguration.

That implies:

- Automatic kinematic verification (no self-collision in allowed modes)

- Torque/force-limit validation per configuration

- “Reduced capability” modes that are certified and predictable

- Clear lockout behavior when constraints can’t be satisfied

Cybersecurity and provenance tracking

If robots can accept modules from other robots, you need provenance:

- Module identity and authenticity checks

- Maintenance history and lifecycle counts

- Tamper detection

Otherwise, the same thing that makes the system resilient can also make it vulnerable.

People also ask (and they should)

Does “self-repair” mean no humans needed?

No. It means fewer emergency interventions. Humans still handle root-cause maintenance, module refurbishment, and process improvements. The difference is that production doesn’t stop while you schedule it.

Won’t modular robots be weaker than fixed-purpose robots?

Often, yes—per kilogram and per dollar. The trade is that modular fleets can keep working through failures and adapt to new tasks. For many operations, uptime and flexibility beat theoretical peak performance.

Is AI required, or is this just mechanical design?

AI isn’t optional if you want real autonomy. The mechanical system can only connect/disconnect. AI is what turns configuration changes into a reliable operational behavior, especially in multi-robot settings.

How to evaluate metabolic modular robots for your automation roadmap

If you’re responsible for robotics strategy, here’s a simple way to sanity-check whether this belongs on your 2025–2027 roadmap.

Start with three measurable criteria

- Downtime cost per hour: If a single robot failure cascades into line stoppage, this approach is worth investigating.

- Task variability: High-mix or seasonal swings (like Q4) favor reconfigurable systems.

- Maintenance capacity constraints: If your team is already stretched, self-repair buys breathing room.

Run a pilot that forces the hard problems

A good pilot isn’t “watch it reconfigure once.” It should include:

- Induced module failures (repeatable fault injection)

- Time-to-recover metrics (minutes, not anecdotes)

- Throughput impact on the donor robot

- Safety validation after each morphology change

If your pilot can’t measure mean time to recover (MTTR), it’s not a pilot—it’s a demo.

What robot metabolism changes about automation strategy

Robot metabolism—self-repairing modular robots that can borrow parts—pushes automation toward systems that don’t just execute tasks, but preserve capability under stress. That’s the difference between impressive robotics and dependable operations.

For the AI in Robotics & Automation series, this is a pivotal theme: AI turns physical modularity into operational resilience. The companies that benefit first won’t be the ones chasing flashy humanoids. They’ll be the ones treating robotics like infrastructure—measured, optimized, and designed to fail gracefully.

If you’re planning new automation for manufacturing, logistics, or service environments, the next smart step is to map where self-repair and reconfiguration would save you the most downtime. Then ask a harder question: what would your operation look like if “maintenance” became a software decision the fleet could make in minutes?