Robot anatomy and design determine whether AI robots succeed in automation. Learn how compliance, sensing, and pHRI design choices boost real-world reliability.

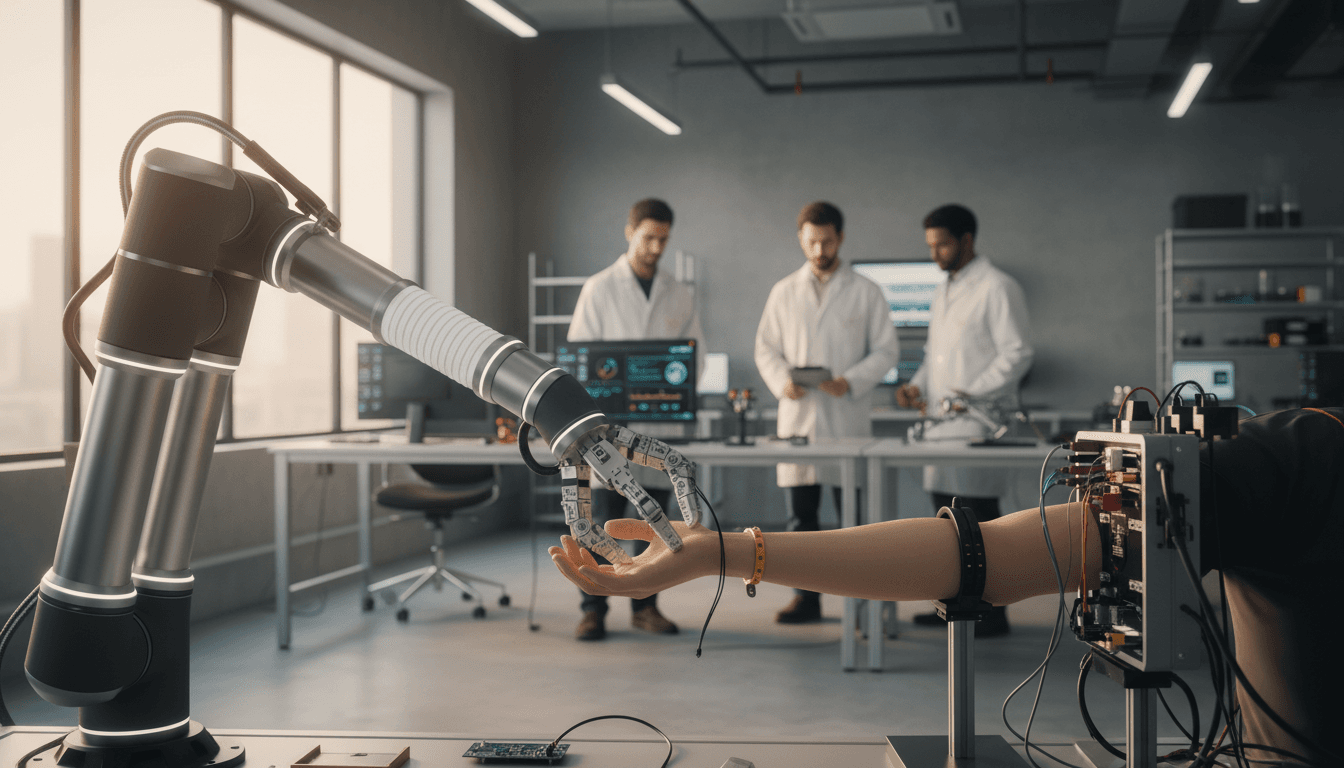

Designing Robot Anatomy for Smarter AI Automation

A robot doesn’t fail in production because its neural network “wasn’t smart enough.” Most of the time, it fails because the body can’t cash the checks the software writes.

That’s why Robot Talk Episode 135—Claire’s conversation with Chapa Sirithunge (University of Cambridge)—lands at exactly the right moment for teams planning 2026 automation roadmaps. As budgets tighten and deployment pressure rises, companies are realizing a simple truth: robot anatomy and design aren’t separate from AI—they’re the foundation that determines whether AI can work at all.

This post sits inside our AI in Robotics & Automation series, where we focus on what actually changes outcomes in manufacturing, healthcare, and logistics. The through-line from the episode is clear: when you design robots with “anatomy thinking” (joints, tendons, compliance, sensing, safety), your AI gets easier to train, safer to operate, and cheaper to maintain.

Robot anatomy is a performance limiter for AI (not an afterthought)

Answer first: If the robot’s mechanics don’t match the task, your AI policy will either overfit, behave unpredictably, or demand expensive sensing and compute to compensate.

A lot of automation programs start with the AI story (“we’ll learn grasping from data” or “we’ll use vision to adapt to variation”), then pick hardware late. I think that’s backwards for most real deployments. Hardware decisions—degrees of freedom (DoF), actuator type, gear ratios, compliance, link lengths, end-effector geometry—define what the robot can physically express.

Here’s a practical way to view “robot anatomy” in AI-enabled robotics:

- Skeleton (structure + DoF): What motions are even possible?

- Muscles (actuators + transmissions): How fast, strong, and efficient is motion?

- Tendons/ligaments (elasticity + compliance): How well does the robot tolerate uncertainty and contact?

- Skin (sensing + protective layers): How does the system perceive force, slip, proximity, and touch?

- Nervous system (control + AI): How decisions convert into stable motion under real constraints.

Chapa’s research focus—assistive robotics, soft robots, and physical human-robot interaction—pushes directly on these boundaries. In contact-rich settings (rehab, elderly care, collaborative workcells), the body must be inherently safe and forgiving, because no perception stack is perfect and no dataset covers every edge case.

Why “smarter AI” can make bad mechanics look worse

AI can amplify both strengths and weaknesses. A stiff, high-gear robot with low backdrivability might hit impressive repeatability in pick-and-place, but the moment you add contact tasks—guiding a patient’s limb, inserting a component, handling flexible packaging—the same stiffness becomes a risk and a tuning nightmare.

If the robot’s anatomy doesn’t allow graceful failure (yielding, absorbing impacts, feeling contact early), the AI/controller ends up doing frantic compensation:

- Higher-frequency control loops

- More sensors (and more integration points to break)

- Conservative speed limits to stay safe

- More exception handling (which kills throughput)

That’s not progress. It’s technical debt with motors.

Human anatomy is still the best design brief we have

Answer first: Human-inspired mechanics—especially compliance and distributed sensing—reduce the burden on AI by making interaction stable by default.

The episode frames a compelling two-way relationship: robots can teach us about human anatomy, and human anatomy can teach us about robot design. The value here isn’t copying the human body for aesthetics. It’s extracting principles that make humans effective in messy environments.

Three principles show up again and again in successful AI-driven robotics deployments:

1) Compliance is a safety feature and a learning feature

Humans don’t hold every joint rigid. We use “softness” to absorb uncertainty. In robotics, compliance can come from:

- Soft materials (soft grippers, padded links)

- Elastic elements (springs, series elastic actuators)

- Control-based compliance (impedance/admittance control)

When compliance is built into the body, policies trained with reinforcement learning or imitation learning often become more robust under distribution shift—small changes in object pose, friction, or contact timing don’t cause catastrophic spikes in force.

2) Tendon-like transmissions can improve efficiency and control

Biology uses tendons to route forces efficiently and store/release energy. In robots, tendon-driven or cable-driven mechanisms can:

- Reduce distal mass (lighter “limbs”)

- Improve backdrivability

- Enable compact, human-scale designs (useful in assistive robotics)

This matters in healthcare and service settings where weight, noise, and perceived safety decide whether people accept the robot.

3) Distributed sensing beats one “perfect” sensor

Humans don’t rely on one sensor for contact. We feel pressure across skin, detect muscle tension, and sense joint angles. Robots benefit from a similar approach:

- Joint encoders + motor current (proxy for torque)

- Force/torque sensors at the wrist

- Tactile arrays in grippers

- Proximity sensors to anticipate contact

You don’t need all of these at once. The point is architectural: design sensing the way you design anatomy—distributed, redundant, and task-driven.

Designing for physical human-robot interaction (pHRI) changes everything

Answer first: If your robot will share space with people, the design target is “safe contact by default,” and AI becomes an assistant—not the sole safety mechanism.

Assistive robotics and pHRI force teams to confront what many industrial deployments can ignore: contact isn’t an exception, it’s the normal operating mode.

In manufacturing, pHRI shows up in collaborative assembly, kitting, and inspection. In healthcare, it’s even more direct—helping a patient stand, guiding a rehab motion, supporting a caregiver.

A useful stance (and one I strongly agree with): don’t ask AI to guarantee safety. Ask the robot’s anatomy to make unsafe behavior hard to express.

That shifts design priorities:

- Favor rounded geometries and pinch-point elimination

- Choose actuators/transmissions that allow controlled yielding

- Add passive compliance where contact is expected

- Use force limits and contact detection as first-class requirements

Practical example: Why soft end-effectors win in mixed-variability tasks

Consider a common automation ask: “Pick a range of SKUs with different packaging from a bin, then place them into totes.” Vision-based grasp planning helps, but the body still determines success.

A rigid parallel-jaw gripper may require:

- Highly accurate pose estimates

- Strict bin presentation

- Frequent re-grasp retries

A soft gripper (or even a rigid gripper with compliant fingertips) reduces the precision burden. The AI can be simpler, training data requirements drop, and recovery behaviors become less frequent. This is anatomy doing what anatomy does: absorbing uncertainty so the brain doesn’t have to.

AI changes what “good robot design” means in 2026

Answer first: With learning-based control and vision, the best robot designs are modular, sensor-rich, and built for data collection—not just motion.

In classic automation, you optimized around repeatability. In AI-enabled robotics, you optimize around adaptability and observability.

Here are four design shifts that matter if you’re deploying AI in robotics & automation over the next 12–18 months:

1) Design for data from day one

If you want policies that improve over time, your robot must produce clean, time-synchronized logs.

Minimum viable “learning-ready” anatomy includes:

- High-quality joint state estimation (position/velocity)

- Reliable timestamps across sensors

- Force/torque or torque estimation for contact tasks

- Room for adding tactile/proximity sensing later

Teams that skip this end up trying to “retrofit observability,” which is expensive and usually incomplete.

2) Put variation in the mechanics, not only the model

You can train a model to handle variation, but it’s often cheaper to change the mechanism:

- Add a compliance element

- Change fingertip geometry

- Add a passive alignment feature for insertion

- Reduce tool weight or inertia

This is especially true in high-mix manufacturing where fixtures are costly and the world won’t stay still.

3) Treat maintainability as an AI performance metric

Dirty sensors, worn belts, slack cables, and drifted calibration will degrade policy performance fast. So “design for maintenance” isn’t a facilities issue—it’s an AI reliability issue.

Ask early:

- How do we re-calibrate in under 15 minutes?

- How do we detect sensor failure automatically?

- Which components are consumables, and what’s the replacement interval?

4) Safety cases must include learning behavior

If your robot uses any adaptive element (online learning, policy updates, auto-tuning), your safety approach has to account for behavior drift.

A practical pattern:

- Keep low-level safety constraints hard-coded (limits, monitors, stop conditions)

- Allow learning inside a constrained “safe envelope”

- Validate policy updates in a sandbox cell before production rollout

This is where anatomy helps again: physical compliance and conservative force limits create a bigger safety buffer.

A field checklist: anatomy-first questions to ask before you buy or build

Answer first: The fastest way to avoid failed pilots is to turn “robot anatomy” into procurement criteria.

If you’re evaluating platforms for manufacturing automation or healthcare robotics, use these questions to pressure-test fit.

Task fit

- What contacts are expected (intentional and accidental)?

- What are the force limits that keep the task safe and damage-free?

- How much positional error can the task tolerate before failure?

Mechanical design

- DoF: Do we have the minimum joints to reach all poses without contortions?

- Backdrivability: Can the robot yield safely under unexpected contact?

- End-effector: Are we relying on “perfect vision,” or do we have mechanical forgiveness?

- Inertia: Is the moving mass low enough for safe collaboration?

Sensing and AI readiness

- Do we have torque/force signals that are stable and well-calibrated?

- Is time sync across vision, encoders, and force signals reliable?

- Can we log data for retraining without extra engineering?

Operations

- How quickly can we re-teach a task when SKUs change?

- What’s the expected downtime for common failures?

- What’s the path from prototype policy to validated production release?

If a vendor can’t answer these clearly, that’s not a “future roadmap” issue. It’s a deployment risk.

Where this is heading: robotics teams that blend anatomy, AI, and empathy

The part of Chapa Sirithunge’s background that I keep coming back to is the mix: assistive robotics + soft robots + physical interaction. That combination is a forcing function for better engineering. You can’t hide behind benchmarks when a robot has to touch a human arm safely or support a person standing up.

For our AI in Robotics & Automation series, this is the bigger lesson: intelligent automation isn’t just smarter models—it’s smarter embodiment. Companies that treat robot design as “hardware plumbing” will keep paying for it in rework, safety constraints, and underwhelming throughput.

If you’re planning an AI robotics initiative for 2026, start with anatomy: design for contact, maintenance, and data. Then bring in AI to optimize behavior within a body that’s already safe and capable.

So here’s the question I’d leave you with: if your current automation plan assumes perfect perception and zero surprises, what would you change in the robot’s anatomy to make that assumption unnecessary?