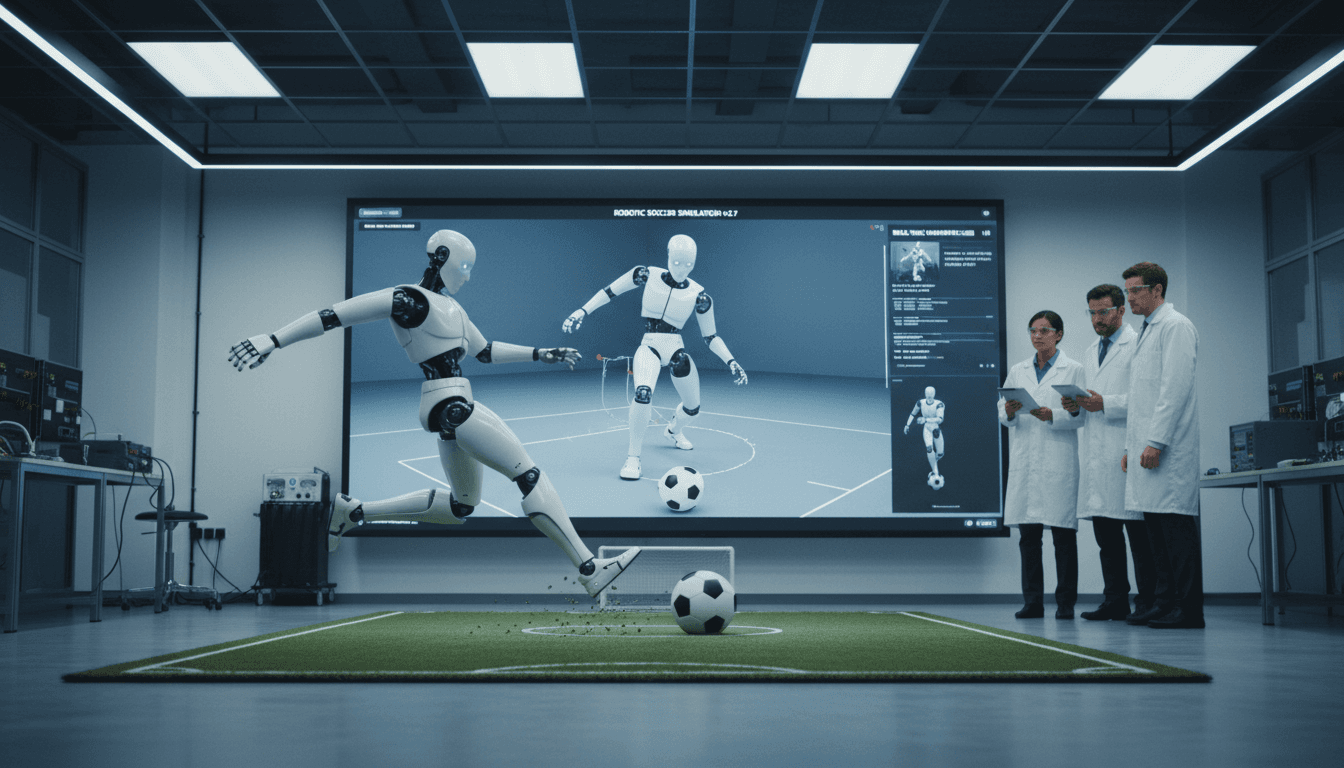

RoboCup’s new MuJoCo-based 3D simulator shows how to close sim-to-real gaps. Here’s what logistics and manufacturing robotics teams can copy.

RoboCup’s New 3D Simulator: What Industry Can Copy

Robots don’t fail in factories because the AI “isn’t smart enough.” They fail because the environment is messy, contact dynamics are unforgiving, and the gap between what worked in simulation and what happens on hardware is still too wide.

That’s why RoboCup’s Soccer 3D Simulation League is worth paying attention to—even if you couldn’t care less about robot soccer. The league is trialing a new MuJoCo-based simulator (alongside the long-running SimSpark) with an explicit goal: make simulation behave more like real robots so learned skills transfer to hardware. If you build robotics for logistics, manufacturing, or inspection, this is the same problem you’re trying to solve—just wearing shin guards.

The practical takeaway: simulation isn’t just a training sandbox anymore; it’s becoming a shared engineering platform for motion, decision-making, and validation. RoboCup’s choices around physics realism, standardization, and multi-agent architecture are directly applicable to industrial robotics and automation.

Why the 3D Simulation League matters beyond soccer

The core idea is simple: the 3D league simulates 11 vs 11 humanoid robots with per-joint control, closer to hardware than “strategy-only” simulations.

In the 2D simulation league, the physics are simplified and the emphasis is team strategy. In the 3D league, the simulator models something much closer to a real robot: walking, balance, ground contact, falls, and actuator behavior. That difference changes what you can learn.

For industrial teams, the connection is straightforward:

- If you’re optimizing motion (walking, manipulation, pushing carts, bimanual handling), you need contact and actuator realism.

- If you’re optimizing coordination (multiple AMRs, mobile manipulators, pick cells, or inspection fleets), you need a simulation that supports independent agents with partial observability.

- If you’re optimizing robustness, you need repeatable scenarios, consistent evaluation, and the ability to change environments without rebuilding everything.

RoboCup’s 3D Simulation League bakes these needs into the competition format, which forces the tooling to evolve in a direction industry can reuse.

The real problem: Sim-to-real isn’t a single gap—it’s five gaps

Most companies talk about “sim2real” as if it’s one hurdle. It’s not. It’s a stack of gaps that compound:

- Actuator gap: torque/velocity limits, servo response, friction, backlash.

- Contact gap: ground contact, compliance, foot slippage, collision response.

- Sensing gap: noise, latency, occlusion, limited field of view.

- Control gap: control frequency, stable gaits, recovery behaviors.

- System gap: middleware/protocols, multi-agent synchronization, resets and rollouts.

SimSpark—created in the early 2000s—was engineered to simulate 22 players at once under old hardware constraints. That meant compromises in physics fidelity and, crucially, a harder time transferring behaviors to physical robots.

The new simulator effort—led by Stefan Glaser with support from the league committee including Klaus Dorer—targets exactly the gaps that matter most: physics realism and practical standardization.

Snippet-worthy stance: If your simulator can’t make your robot fall the way real robots fall, it also can’t teach your robot to recover the way real robots recover.

Why MuJoCo (and why standardization beats “more features”)

The MuJoCo-based direction isn’t about chasing a trendy engine. It’s about removing friction that stops teams from experimenting.

SimSpark’s strengths—and why they still became a barrier

SimSpark is powerful and flexible: plugin-based, scriptable, and able to use different physics backends. The downside is what you’d expect:

- Complexity tax: flexibility comes with a steep learning curve.

- Custom model specifications and protocols: teams need bespoke robot models and communication layers.

- Lower adoption outside the league: fewer shared tools, fewer reusable assets.

In industrial robotics, you see the same pattern when simulation environments become “frameworks you need a specialist to operate.” Adoption stalls. Iteration slows. The tool becomes a bottleneck.

MuJoCo’s practical advantages

Glaser’s approach uses MuJoCo because it’s widely adopted in the machine learning community, has a large ecosystem of robot models, and supports a critical feature added recently: modifying the world during simulation while preserving state.

That last point matters more than it sounds. In RoboCup 3D Simulation League, agents connect on demand; teams form dynamically; the server must manage multiple independent agent processes.

In an industrial context, this maps cleanly to:

- Adding/removing pallets, bins, or fixtures mid-run

- Spawning tasks dynamically in a fleet simulation

- Switching tooling configurations without restarting everything

- Running large-scale training rollouts without brittle reset logic

Glaser also made a pragmatic decision that many robotics orgs should copy: start in Python to reduce complexity and increase contributor accessibility, then optimize performance later when bottlenecks are proven.

Multi-agent simulation: the architecture industry keeps underestimating

A key design detail in RoboCup 3D is that it’s not one monolithic “game AI.” It’s 22 separate agent programs connected to a simulation server.

Each agent:

- Controls a single robot

- Receives only its own sensor data

- Has limited virtual vision (not full world state)

- Communicates only via the server (no direct agent-to-agent channel)

This is closer to real deployments than many industrial demos.

Why partial observability is the point

In warehouses and factories, robots don’t get perfect state:

- Cameras miss detections.

- QR codes get occluded.

- People walk through lidar scans.

- Wireless introduces jitter.

RoboCup’s design forces teams to build policies that work under realistic constraints. The simulator provides detections (labels, direction vectors, distances) with noise, similar to a real perception stack—but without requiring raw image processing in the first version.

That’s a smart trade.

Here’s what works in practice (I’ve seen this pattern hold across robotics teams):

- Start with structured observations to focus on control and decision-making.

- Add pixels later when the control loop is stable and you can measure the value of end-to-end perception.

If you jump straight to camera images, you often end up benchmarking vision models instead of building robots that finish tasks.

Physics realism: better motors, harsher ground contact, more truth

Klaus Dorer described an early experiment where the robot collapsed—and it collapsed like real hardware. That’s the whole point.

The new simulator supports more realistic actuator control modes (speed, force, position). It also makes ground contact less forgiving. In SimSpark, robots could “get away with” hard steps. In the MuJoCo-based simulator, that same step can cause a fall.

For industrial robotics and automation, this maps directly to:

- Mobile manipulators tipping when acceleration is too aggressive

- Legged robots losing footing on imperfect contact

- Grippers slipping when friction is mis-modeled

- Conveyed parts bouncing or rolling differently than expected

Actionable checklist: what to validate when you upgrade simulator fidelity

If you’re moving to a more realistic physics model (or tightening your parameters), test these first:

- Motor saturation behavior: do controllers behave sensibly at limits?

- Contact stability: does small foot/hand placement error cause realistic slip?

- Energy consistency: do impacts look plausible or “floaty”?

- Recovery behaviors: can your policy regain balance, or does it fail catastrophically?

- Repeatability under noise: do results hold with sensor noise and latency?

RoboCup’s kick-distance challenge is a good example of a “single-skill benchmark” that isolates physics and control quality before full-game complexity. Industrial teams should do the same: validate primitives (push, pick, place, dock) before full workflows.

RoboCup 2025’s “Kick Challenge” is more than a demo

The league plans to trial the simulator at RoboCup 2025 with a voluntary challenge: a single robot steps to the ball and kicks as far as possible.

That sounds narrow, but it’s an excellent diagnostic task because it combines:

- Stable approach gait

- Foot placement precision

- Timing and actuator control

- Contact dynamics between foot and ball

- Whole-body balance and recovery

In other words, it’s a compact sim2real test. For industrial robotics, the equivalent is something like:

- “Approach and dock with max repeatability”

- “Pick from bin with max success rate under randomized clutter”

- “Push object to target with max accuracy under friction variation”

The value is that you can compare teams (or internal approaches) on a crisp metric while still learning about system-level weaknesses.

The hidden opportunity: AI refereeing as a template for safety and policy enforcement

Simulation leagues have a built-in advantage: the system knows the true world state. Refereeing can be automated and deterministic.

Dorer also points out a future direction: learning-based foul detection trained from human referee judgments, since some fouls are debatable and hard-coded rules can be brittle.

Industrial automation has the same need under different names:

- Safety envelope violations

- Human-robot interaction policy enforcement

- “Near miss” event detection

- Compliance with facility rules (speed zones, no-go areas)

A practical stance here: start with an expert system for enforceable constraints, then add learning for the gray areas. That’s also how the simulator roadmap is framed: expert-rule referee first, AI-based models second.

How to apply these lessons to logistics and manufacturing robotics

Here’s a concrete playbook you can lift from RoboCup’s direction if you’re building AI-driven robotics and automation.

1) Choose standard models and protocols early

If your simulator needs custom robot descriptions and custom comms, you’re building a second product: tooling. Standard model formats and widely used physics engines lower friction and expand hiring options.

2) Build a “server + agents” architecture for training

Treat each robot as an independent process with:

- Partial observations

- No direct peer-to-peer shortcuts (unless your real system has them)

- Realistic comms latency and packet loss knobs

That’s how you avoid policies that only work in perfect coordination.

3) Use skill challenges to de-risk sim2real

Before you run a full facility digital twin, measure primitives:

- docking

- pushing

- grasping

- navigation in dense traffic

- recovery from disturbances

One metric, many rollouts, tight feedback.

4) Invite the community—or at least your internal stakeholders—to tune physics

Glaser explicitly calls out the need for shared evidence when choosing parameters (ball behavior is one example). In industry, physics parameters often become “tribal knowledge.” Don’t accept that.

Run controlled experiments on hardware, publish the parameter rationale internally, and treat parameter sets as versioned assets.

Where this is heading for AI in robotics & automation

The bigger story for the AI in Robotics & Automation series is that simulation is becoming a common layer across domains: soccer, humanoids, standard platforms, warehouses, and factories. When simulators standardize and become easier to extend, the winners are the teams that iterate fastest—because they can train more, test more, and break fewer things on hardware.

RoboCup’s MuJoCo-based simulator effort is a clean signal: the community is prioritizing realism, interoperability, and multi-agent training loops over legacy complexity. That combination is exactly what industrial robotics teams need if they want robots that are adaptable, not just impressive in controlled demos.

If you’re evaluating your own simulation strategy for 2026 planning—new robot deployments, new automation cells, or broader fleet autonomy—ask one blunt question: Are you building a simulator that your AI can learn from, or a simulator that only produces pretty videos?