Quantifying reinforcement learning generalization helps robotics and digital automation perform reliably under real-world change. Learn metrics, tests, and rollout tactics.

Reinforcement Learning Generalization You Can Measure

Most AI failures in automation aren’t caused by “bad models.” They’re caused by bad assumptions about where the model will work.

A robot that performs flawlessly on a tidy demo line might stall the first time a pallet arrives rotated 10 degrees. A customer support agent that nails common questions may spiral when a user mixes two issues in one message. Same pattern, different domain: the system learned a task, but it didn’t learn to generalize.

That’s why quantifying generalization in reinforcement learning matters—especially for U.S. tech companies shipping AI into real products. Reinforcement learning (RL) is a backbone technique in robotics and automation, and it increasingly shows up behind the scenes in digital services: routing decisions, tool use, dialog policies, scheduling, and adaptive workflows. The uncomfortable truth is that many RL “wins” are still benchmark-dependent. If you can’t measure generalization, you can’t manage it.

What “generalization in RL” really means (and why teams get it wrong)

Generalization in reinforcement learning is the ability of a trained policy to succeed when the world changes in small but realistic ways. It’s not just “doing well on the test set” like in supervised learning, because in RL the agent’s actions change what data it sees.

In practice, teams often overestimate generalization because they evaluate on environments that are too similar to training. You’ll see strong results when:

- The initial conditions are narrow (same start state every time)

- The environment is deterministic (no noise, no drift)

- The task distribution is static (no new variants)

- Success is defined in a way that hides brittleness (e.g., reward shaping that masks failure modes)

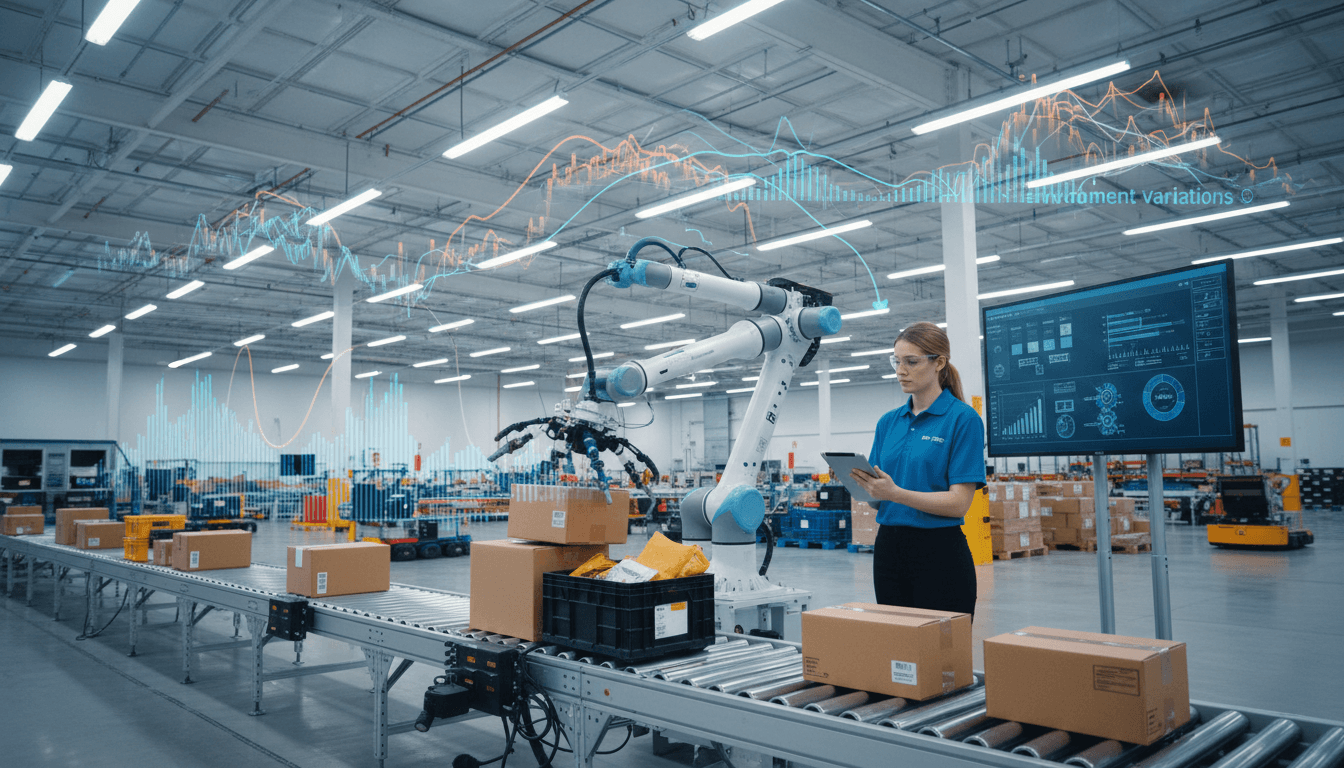

Why this matters in robotics and automation

Robots are basically generalization stress tests.

A warehouse robot sees different floor friction after a rainy day. A healthcare service robot encounters a new hallway obstacle layout. A manufacturing cobot handles slightly different parts from a new supplier. In each case, you didn’t “change the task” from a business standpoint—but the agent’s world changed enough to expose fragility.

If you can quantify generalization, you can decide where RL is safe to deploy and where you need guardrails. That’s the difference between a pilot and a scalable system.

Why this matters in U.S. digital services and SaaS

RL isn’t only for physical control. Many U.S.-based SaaS platforms now use RL-style loops for:

- Dynamic workflow optimization (which step next, which tool to call)

- Customer communication policies (when to escalate, what to ask next)

- Personalization and recommendation under constraints

- Budget pacing and bidding strategies in marketing automation

The generalization problem shows up as: it worked last month, then it quietly stopped working. Measuring generalization is how you prevent that from becoming your normal operating mode.

The core challenge: RL benchmarks often reward memorization

The hardest part about generalization in RL is that agents can “cheat” without anyone noticing. They can latch onto quirks in the training simulator, exploit deterministic patterns, or overfit to narrow dynamics.

Here’s what I’ve found in practice: if you don’t deliberately design evaluation to punish shortcuts, the model will find shortcuts.

Three common ways RL systems overfit

- Environment overfitting: The agent learns simulator artifacts (timing, physics quirks, visual textures) rather than task-relevant structure.

- Trajectory overfitting: The agent learns one good path and collapses when forced off it.

- Reward overfitting: The agent optimizes the reward function’s loopholes instead of the intended outcome.

This is why “it got a high score” isn’t enough. You want an evaluation that answers: will this still work when reality isn’t polite?

How to quantify generalization: metrics that product teams can actually use

A useful generalization score in RL compares performance across controlled shifts in the task distribution. The point isn’t to create academic perfection—it’s to create a repeatable, decision-grade measurement.

Below are evaluation patterns that translate well from research into product and operations.

1) In-distribution vs out-of-distribution (OOD) splits for RL

Treat environments like datasets. Build:

- Training distribution: the scenarios you train on

- Validation distribution: same family, new random seeds and initializations

- OOD distribution: meaningful shifts (new layouts, different dynamics, novel combinations)

Then compute:

- Generalization gap = Performance(ID) − Performance(OOD)

A small gap means the policy is robust. A large gap means you’ve probably trained a specialist.

2) Stress testing via “nuisance variables”

Nuisance variables are factors that shouldn’t change the goal but often break the policy.

Robotics examples:

- Lighting variation, sensor noise, camera blur

- Friction coefficients, payload mass, motor lag

- Slight geometry changes in objects and bins

Digital services examples:

- Longer user messages, typos, mixed intents

- Delays in tool responses, partial failures

- Changes in business rules (holiday schedules, return windows)

A practical approach is to vary one nuisance factor at a time and plot performance curves. This yields a robustness profile rather than a single number.

3) “Holdout tasks” that represent real business drift

Most companies already know what drift looks like:

- New product line launches

- New market segments

- Policy updates (privacy, compliance)

- Seasonal shifts (and yes, late December is a perfect example)

So measure generalization on purpose-built holdouts that mimic those shifts. If you’re in retail logistics, evaluate the week after Black Friday and the week before Christmas—peak volume behavior is different even if the task is “the same.”

A policy that can’t handle predictable seasonal drift isn’t intelligent—it’s just well-trained on last quarter.

What “good” generalization looks like in automation systems

Good RL generalization is visible as graceful degradation, not sudden collapse.

In robotics, that means when conditions shift, the robot slows down, re-plans, asks for help, or switches to a safe fallback controller. In SaaS automation, it means the agent escalates, requests clarification, or chooses a conservative workflow path.

Design pattern: pair RL policies with safety rails

If you’re deploying RL in robotics & automation, I’m opinionated about this: don’t ship a naked policy. Ship a system.

A reliable architecture often includes:

- A policy (RL) for action selection

- A constraint layer (rules, safety controller, or verifier)

- A fallback strategy (classical controller, scripted workflow, or human-in-the-loop)

- A monitor that detects when the state is off-distribution

Generalization metrics tell you when the monitor should trigger and how often you should expect it to trigger.

Practical examples: generalization in the U.S. digital economy

Generalization isn’t academic. It directly impacts cost, reliability, and user trust. Here are concrete scenarios where quantifying generalization changes decisions.

Example 1: Warehouse picking robots and “new SKU week”

A picking policy trained on common packaging types might fail on a new SKU batch with glossy wrap and different reflectivity. If you’ve quantified OOD performance on reflective surfaces and new object geometries, you can predict:

- Whether the policy will hold up

- Whether you need more simulation randomization

- Whether to route those SKUs to a different station until retraining completes

Example 2: Customer communication automation with RL-style policies

Many support systems use policy optimization to decide the next best action: ask a question, call a tool, offer a refund path, or escalate.

Quantifying generalization here means measuring behavior under:

- Novel combinations of intents (billing + technical)

- Tool downtime (refund API returns error)

- Policy changes (holiday return exceptions)

If your OOD evaluation shows a steep drop when tools fail, your roadmap is obvious: build tool-failure training and conservative fallback behaviors before you scale volume.

Example 3: Service robots in healthcare facilities

Hospitals change layouts. Equipment moves. Hallways get blocked. A navigation policy that only succeeds in a static map isn’t ready.

Generalization metrics can define readiness criteria like:

- “At least 95% success across randomized obstacle layouts”

- “No more than 2% emergency stops under sensor noise level X”

These are procurement-friendly, compliance-friendly numbers—much easier to defend than “the model looked good in the lab.”

A field guide: how to improve RL generalization (without guessing)

The fastest way to improve generalization is to treat it as an engineering target with feedback loops. Here’s a practical checklist that works in robotics and in digital automation.

1) Expand the training distribution intentionally

Don’t just add more data. Add the right variation.

- Use domain randomization (physics, visuals, timing)

- Randomize initial states and goal configurations

- Introduce rare-but-real events (slips, occlusions, tool errors)

2) Penalize brittle behavior

If the reward only cares about success, agents learn risky shortcuts.

Add shaping that reflects operations:

- Smoothness penalties (jerk, oscillations)

- Safety penalties (near-collisions, constraint violations)

- Cost penalties (excess tool calls, long resolution paths)

3) Evaluate like an adversary, not a fan

Build an evaluation harness that tries to break the agent:

- Seed sweeps (hundreds to thousands)

- Parameter sweeps (noise levels, delays)

- Scenario combinatorics (two changes at once)

If you can’t automate the test harness, generalization work won’t stick. It’ll become a one-time “research sprint” that disappears when deadlines hit.

4) Add monitoring for OOD detection in production

Generalization isn’t a one-and-done property. Production shifts.

Useful signals:

- State distribution drift (embeddings, sensor stats)

- Spike in fallback activations

- Spike in retries, timeouts, or near-miss events

Then create a rule: when OOD rises, retraining is mandatory—not optional.

People also ask: quick answers on RL generalization

Is reinforcement learning required for automation?

No. Classical control and optimization still win many tasks. RL shines when the environment is complex, partially observed, or when hand-engineering a policy is too slow. The catch is you must measure and manage generalization.

What’s the difference between robustness and generalization?

Robustness is performance under noise and perturbations. Generalization is performance under broader shifts—new scenarios, new combinations, and distribution changes. In practice, robustness testing is a subset of generalization testing.

Can you quantify generalization without a simulator?

Yes, but it’s harder. You can use staged rollouts, shadow mode, A/B policy testing, and offline evaluation with logged data. In robotics, a high-quality simulator still provides the safest way to generate diverse OOD tests quickly.

Where this fits in our “AI in Robotics & Automation” series

Reinforcement learning is one of the most promising tools in robotics & automation, but it has a credibility problem: impressive demos that don’t survive contact with real operations. Quantifying generalization in reinforcement learning is how the field grows up.

For U.S. technology and digital services companies, this is directly tied to scaling: fewer brittle automations, fewer surprise regressions, and clearer go/no-go decisions for rollout. If you’re building AI-driven workflows—physical or digital—generalization measurement should sit next to latency, cost, and reliability as a first-class metric.

If you’re evaluating an RL system right now, here’s the next step I’d take this week: define your top 10 “the world changed” scenarios, build an OOD test set around them, and track the generalization gap every model iteration. What would you ship differently if that number was on your dashboard?