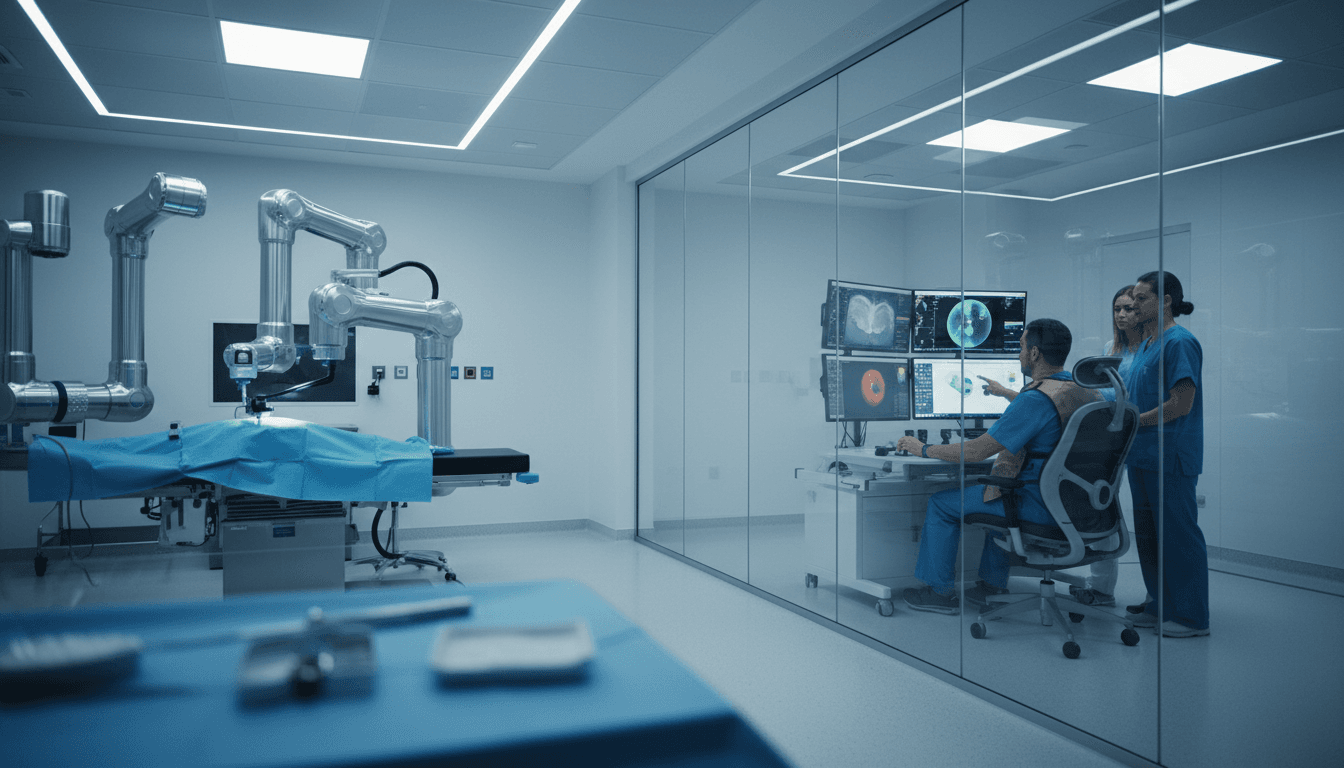

Remote robotic thrombectomy can cut hours off stroke treatment by bringing expert control to rural hospitals. See how AI-assisted telerobotics is evolving.

Remote Robotic Thrombectomy: Faster Stroke Care

About 2 million neurons die each minute during an ischemic stroke when blood flow is blocked. That number is brutal, but it’s also useful: it turns “access to care” into a measurable engineering problem. If your region can’t get a patient to an endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) team for six hours, the outcome gap isn’t mysterious—it’s designed into the system.

Remote robotics is one of the first credible ways to redesign it.

Over the past few months, two public demos moved telerobotic stroke intervention from “science project” to “early deployment roadmap.” In Toronto, clinicians used a robotic system to perform brain angiograms from one hospital while the patient was in another, supported by a bedside team. Separately, a transatlantic simulation showed that remote control of EVT-like catheter work is technically feasible even with meaningful distance.

For readers following our AI in Robotics & Automation series, this is a clean case study: robotics + networking + human workflow + (in one approach) AI assistance. Not a lab robot doing perfect tasks in perfect conditions—a system trying to deliver life-saving performance inside messy reality.

Why remote EVT is a robotics problem, not a telehealth problem

Remote stroke treatment isn’t mainly about video visits. It’s about whether you can safely and precisely manipulate guidewires and catheters through fragile vessels while relying on live imaging and a distributed team.

EVT (endovascular thrombectomy) is the standard intervention for a common, severe type of ischemic stroke caused by large vessel occlusion. An experienced clinician navigates from an access point (often the femoral artery) up to the brain to remove the clot. The timeline is unforgiving.

“Time is brain” isn’t a slogan. It’s an operating constraint.

Remote robotics targets the worst bottleneck: specialist scarcity combined with geography. Some regions simply don’t have enough neurointerventionalists to staff every hospital that might receive stroke patients.

Remote robotic EVT changes the equation from:

- “Move the patient to the expert”

to:

- “Move the expert’s hands to the patient”

And it does that without pretending the bedside team disappears.

The reality check most people miss: bedside staff are still required

A common misconception is that “remote” means no skilled people in the room. In practice, remote EVT still depends on a bedside team for:

- patient prep, sedation coordination, and sterile field management

- device loading and swapping components as the procedure progresses

- repositioning imaging (fluoroscopy) and managing the physical environment

- rapid response if anything unexpected happens

So the success metric isn’t “remove all staff.” It’s shift scarce expertise (the neurointerventionalist) so one specialist can cover multiple locations, while bedside clinicians handle standardized steps with training and protocols.

That division of labor is classic automation design: keep humans where they’re strongest, automate or remote-enable the constraint.

What the recent demos prove (and what they don’t)

Two demonstrations matter because they addressed different “show-stoppers.”

- Toronto: Remote brain angiograms between hospitals, with a clinician controlling a robotic system from a distance.

- Jacksonville–Dundee (simulation): A remote EVT-style setup spanning an ocean, demonstrating feasibility even with non-trivial latency.

The point isn’t that anyone needs to do transatlantic stroke care. The point is that if it works across the Atlantic, it can work across a state, province, or rural catchment area—where the need is real.

Latency isn’t the villain people think it is

In the simulated transatlantic setup, reported latency was around 120 milliseconds. That’s not nothing, but EVT isn’t a twitch shooter. The motion profile is careful and deliberate, and the procedure is guided continuously by imaging.

The bigger networking risk is reliability, not just delay.

A serious telerobotic system needs:

- redundant network paths

- continuous connection-quality monitoring

- safe-state behavior if packets drop or quality degrades

- explicit handoff protocols between remote operator and bedside team

In other words: the robot must be designed to fail safely, not just operate smoothly.

Two design philosophies: “AI-forward” vs “surgeon-feel-first”

The most interesting part of the current market isn’t that robots can move catheters. It’s that teams are making very different bets on how humans should control a remote intervention.

Approach 1: Software-centric control with AI assistance

One system leans into a software interface that can be controlled with a laptop-like setup. The AI angle shows up in two practical places:

- guidewire manipulation assistance: machine learning-informed behaviors that can stabilize or standardize aspects of movement

- image overlays: informational layers on top of X-ray imaging to help the remote clinician interpret position and progress

This approach is a bet that:

- training time can be shortened with software guidance

- remote operation becomes “call-center-like” for specialists (centralized coverage)

- the system improves over time because the product captures data at scale

If you’ve worked in industrial automation, the pattern will feel familiar: turn craft into process, then turn process into software.

Approach 2: A control console that mimics manual technique (with force feedback)

The other approach prioritizes a console that replicates how clinicians already operate catheters and guidewires, including force feedback that mimics tactile resistance.

That’s a bet that:

- intuitive control matters more than AI assistance early on

- adoption accelerates if the robot “feels” like existing manual workflows

- the platform can later add AI once it has enough real-world training data

I like this honesty: you don’t get good training data until you ship capable hardware into real workflows.

My take: the winner will combine both, but not equally

In the near term, human factors will drive adoption: intuitive controls, predictable behavior, and trust in safe-state operation.

In the medium term, AI will matter most in the parts no one wants to admit are messy:

- reducing cognitive load while monitoring multiple imaging streams

- standardizing routine motions and device transitions

- flagging risk patterns early (e.g., unusual resistance, anatomy anomalies)

- documenting the procedure automatically for audit and training

The winning systems will treat AI as an operator advantage, not an operator replacement.

The unglamorous constraints that will decide clinical rollout

Remote robotic stroke intervention won’t be limited by robotics alone. It’ll be limited by how well vendors and hospitals solve four operational constraints.

1) Workflow: who does what, exactly, at the bedside?

Hospitals will demand clarity:

- Which steps require a trained interventionist vs a standardized bedside role?

- How many bedside staff are needed at 2 a.m.?

- What’s the escalation path if something goes off-script?

A remote EVT program succeeds when it has boring, repeatable checklists.

2) Training: standardizing competency across distributed sites

Because bedside staff remain essential, training has to be designed like other safety-critical industries:

- simulation-based credentialing

- periodic recertification

- drills for “network dropout,” “device jam,” “unexpected anatomy,” and “bleed risk” scenarios

Hospitals won’t accept “it’s easy to learn” as evidence. They’ll accept performance data.

3) Reliability engineering: redundant networks and fail-safe robotics

Remote robotics changes the risk profile. A safe device must:

- continuously validate connection quality

- prevent unintended motion during degraded connectivity

- provide “freeze” or retract-to-safe behavior

- log events with high resolution for post-procedure review

This is where robotics engineers earn their keep: safety isn’t a feature, it’s architecture.

4) Regulation and procurement: start local, prove outcomes, then expand

A realistic commercialization path is:

- local, on-premise robotic assistance for endovascular procedures

- build a safety record and usage volume

- expand to remote use cases with clear protocols

That sequence reduces risk and also makes the business case easier: hospitals can justify utilization before betting on full remote capability.

What healthcare teaches the rest of robotics & automation

Stroke robotics is a harsh proving ground, and that’s exactly why it’s valuable for anyone building AI-enabled automation.

Lesson 1: “Automation” often means “redistribution”

Remote EVT doesn’t erase humans. It redistributes human work to match scarcity. That same idea applies to:

- remote maintenance in industrial plants

- teleoperation in hazardous logistics environments

- expert-in-the-loop QA in manufacturing

Lesson 2: Data advantage comes from deployment, not demos

Both remote robotics approaches talk about data—images, force signals, system telemetry. The organizations that get real clinical usage will collect the datasets that make AI actually useful.

That’s the pragmatic flywheel:

- deploy hardware → collect multimodal data → improve assistance → earn trust → deploy more

Lesson 3: Safe-state design is the real AI product

In safety-critical robotics, the “smart” part isn’t only the ML model. It’s the system’s ability to:

- detect uncertainty (network, sensor, user input)

- constrain actions under uncertainty

- degrade gracefully

If you’re building AI-enabled robots in any industry, that trio matters more than your demo accuracy.

Practical next steps for hospitals and robotics teams evaluating remote EVT

If you’re a provider group, medtech team, or health system leader exploring remote robotic thrombectomy, here’s a shortlist that cuts through the hype.

A readiness checklist worth using

- Map your time-to-treatment gap. Identify which transfers routinely exceed 60–120 minutes and quantify outcomes impact.

- Define bedside roles. Write down exactly who does device prep, sterile steps, imaging alignment, and emergency response.

- Pressure-test connectivity. Evaluate redundant network options and simulate dropouts.

- Demand simulation training. Don’t negotiate on this. If there isn’t a structured curriculum, you’re buying risk.

- Start with adjacent procedures. Build utilization and competency before pushing to the highest-acuity remote cases.

The ROI story that actually holds up

The strongest ROI argument isn’t “robots are cool.” It’s:

- fewer long-distance transfers

- faster access to EVT

- reduced disability burden (which dominates lifetime cost)

- better specialist utilization across a region

If your pilot can’t tie itself to those metrics, it’s not a pilot—it’s a tech showcase.

Where this goes next in 2026

Clinical trials for on-premise neurointerventions are expected to accelerate in 2026, and remote trials will follow as safety cases and training programs mature. Meanwhile, broader endovascular use (outside stroke) will likely be the first commercial foothold in multiple regions.

From the perspective of the AI in Robotics & Automation series, remote robotic thrombectomy is an early signal of where intelligent automation is headed: systems that combine robotics, operator-in-the-loop control, and AI assistance to deliver expert performance where experts aren’t.

The biggest open question isn’t whether remote EVT can be done. It’s whether health systems can operationalize it reliably—across staffing, training, networks, and reimbursement—without turning every case into a bespoke hero mission.

If you’re building or buying robotics for high-stakes environments, that’s the bar to aim for: repeatable excellence, not occasional brilliance.