Point‑E turns complex prompts into 3D point clouds you can refine into meshes, sims, or prototypes—ideal for robotics, design, and U.S. digital services.

Point-E: Turn Text Prompts Into Fast 3D Prototypes

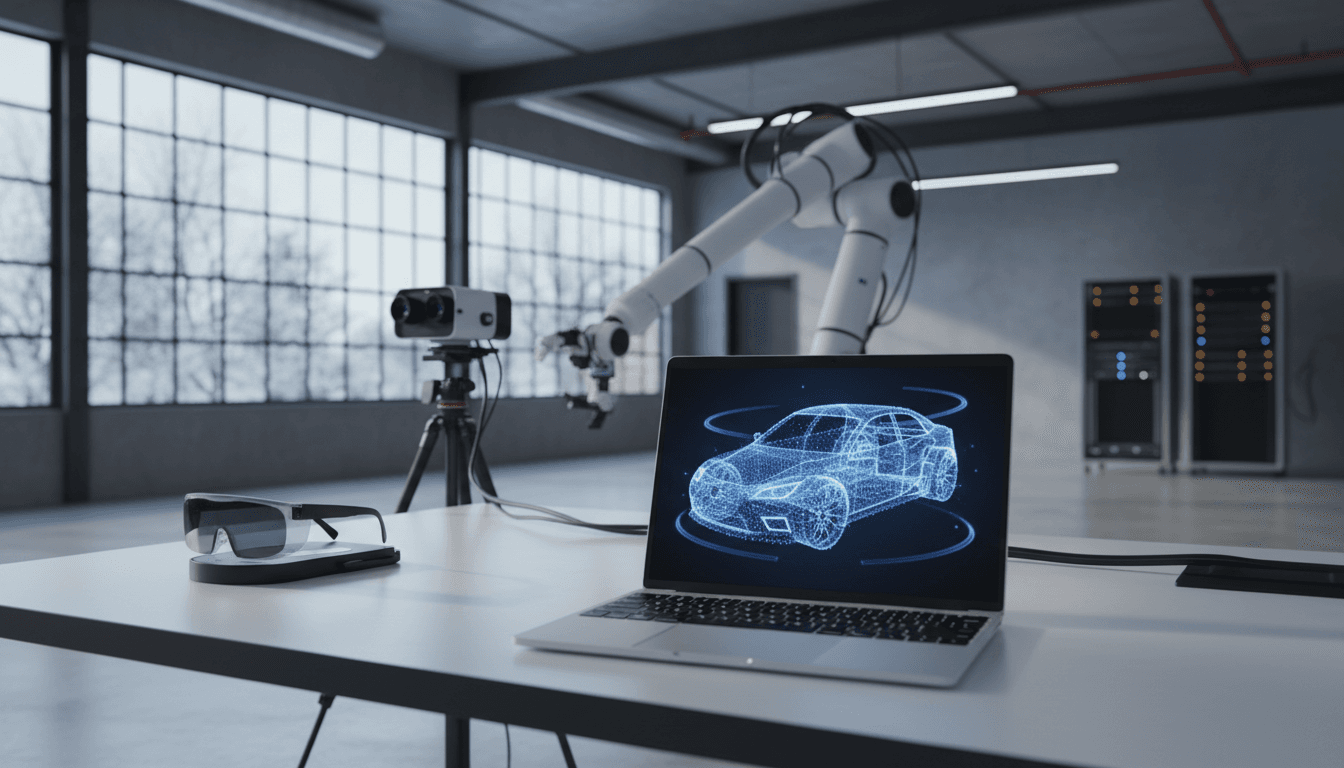

A lot of AI demos look impressive until you try to plug them into real production. Text-to-3D is different: when it works, it shortens an entire design loop, not just a task. Point‑E—an approach for generating 3D point clouds from complex prompts—is a practical example of that shift, especially for U.S. teams building digital products, robotics simulations, e-commerce visuals, or architectural concepts.

Here’s the real value: point clouds are a lightweight “first draft” of 3D. They don’t pretend to be final CAD. They’re closer to a rapid sketch you can rotate, measure, and refine. For automation and robotics, that’s huge because rough geometry is often enough to start simulation, grasp planning, collision checks, and layout planning.

This post sits in our AI in Robotics & Automation series, where the theme is consistent: AI isn’t replacing engineering—it’s compressing iteration cycles. Point‑E is a clean case study in how generative AI can power next-generation digital services in the United States.

What Point‑E actually generates (and why point clouds matter)

Point‑E generates 3D point clouds—sets of (x, y, z) coordinates that approximate an object’s surface—directly from text prompts. That single sentence explains both its strength and its limitation.

A point cloud is not a watertight mesh. It won’t have clean edges, perfect symmetry, or manufacturable tolerances. But it is:

- Fast to create compared with traditional modeling

- Easy to render and inspect from multiple angles

- Useful for downstream conversion (mesh reconstruction, voxelization, SDF fitting)

- Good enough for many automation tasks, where approximate geometry beats no geometry

In robotics and automation workflows, point clouds are already a native data type. Depth cameras (stereo, LiDAR, structured light) feed point clouds into perception stacks every day. So a model that can generate point clouds from text isn’t just a novelty—it matches a format automation systems already know how to handle.

A snippet-worthy definition you can share internally

Point‑E is a text-to-3D method that produces point clouds as an initial 3D draft, trading perfect topology for speed and flexibility.

How text-to-3D works in practice: the Point‑E pipeline

Most text-to-3D systems have to solve the same problem: language is high-level, 3D geometry is precise. Point‑E’s practical approach is to break the task into stages rather than trying to “think in 3D” all at once.

A common pattern (and the one typically associated with Point‑E-style systems) looks like this:

- Text prompt → coarse visual prior: generate or infer a 2D representation (often an image) consistent with the prompt.

- 2D prior → 3D point cloud: predict a set of 3D points that match the object implied by the prompt.

- Optional refinement: densify points, reduce noise, and improve consistency.

This staged approach matters because it’s computationally friendly. Compared with optimizing a full 3D mesh through expensive differentiable rendering loops, generating a point cloud can be cheaper and faster—exactly what you want for rapid prototyping.

Why complex prompts are the real benchmark

Simple prompts (“a chair”) are easy to fake. Complex prompts stress whether the system can keep attributes straight:

- Composition: “a drone carrying a small medical box under its belly”

- Materials: “a brushed aluminum flashlight with a rubber grip”

- Style: “mid-century modern table lamp with a conical shade”

- Constraints: “a warehouse pallet jack with extended forks”

When a system can preserve those attributes in 3D, it becomes useful for design and automation teams, not just research demos.

Where Point‑E fits in U.S. tech: digital services built on 3D generation

Point‑E is best understood as an enabling layer for digital services, not a standalone product. In the U.S. market, there’s a clear pattern: teams want to generate 3D assets faster, then route them into existing pipelines.

Here are high-value places I’ve seen point-cloud-first generation make sense.

Robotics simulation and automation planning

If you’re building a robotics application, you often need “good enough geometry” early:

- Synthetic scene generation for training and testing

- Digital twins for basic layout planning

- Collision approximations for reachability studies

- Grasp candidate generation where rough surface coverage is sufficient

A point cloud can be converted to occupancy grids or signed distance fields for simulation. That means Point‑E-style outputs can become inputs to robotics stacks relatively quickly.

Architecture and built environment concepts

Architectural teams don’t want a perfect BIM model on day one. They want options.

Text-to-3D point clouds can help generate:

- Massing studies (rough volumes)

- Furniture and fixture placeholders

- Conceptual site elements for early visualization

The big win is speed: you can explore multiple directions before committing to detailed modeling.

Digital product development and e-commerce content

U.S. retailers and product teams spend real money creating 3D assets for AR viewers and configurators. A point-cloud-first workflow can shorten early-stage tasks:

- Rapid shape exploration

- Variant ideation (colors, styles, attachments)

- Early marketing visualization drafts

Later, artists can rebuild a clean mesh, but they start with a 3D “sketch” rather than a blank scene.

Turning point clouds into production assets: what to do next

A Point‑E point cloud is usually the beginning of the pipeline, not the end. To use the output in real tools (Unity, Unreal, CAD prep, simulation engines), you’ll want a conversion path.

Common post-processing steps

-

Denoise and outlier removal

- Statistical outlier filtering removes floating points.

- Radius-based pruning tightens surfaces.

-

Normalize scale and orientation

- Prompted generation can be ambiguous about size.

- Standardize units early (meters vs. millimeters) to avoid downstream chaos.

-

Surface reconstruction (point cloud → mesh)

- Poisson reconstruction is common for smooth shapes.

- Ball pivoting can preserve sharper features if the sampling is dense.

-

Retopology and UVs (if you need real-time rendering)

- Automation helps, but manual cleanup is still normal for hero assets.

-

Physics proxies (for robotics/simulation)

- You may not need a full mesh.

- A simplified collision hull (convex decomposition) is often enough.

A practical “good pipeline” for automation teams

If you’re building robotics demos or internal simulation tools, this workflow tends to hold up:

- Generate point cloud from prompt

- Voxelize into an occupancy grid

- Create a simplified collision proxy

- Run simulation for reach, collision, and basic interactions

This keeps you from over-investing in photoreal assets when what you need is functional geometry.

Limits, risks, and how to evaluate quality without fooling yourself

The biggest risk with text-to-3D point clouds is false confidence. A model can produce something that looks plausible from one angle and collapses from another.

The three failure modes I’d watch for

-

Multi-view inconsistency

- Rotating reveals missing surfaces or “inside-out” geometry.

-

Prompt attribute drift

- The model keeps “chair” but loses “foldable” or “with armrests.”

-

Scale ambiguity

- A “robot arm” might come out the size of a desk toy unless you specify constraints.

A simple evaluation checklist (works for product teams)

Use this when deciding whether Point‑E-style generation is viable for your use case:

- Prompt fidelity: Does it preserve the top 3 required attributes?

- Surface coverage: Is the point density sufficient for reconstruction?

- Symmetry and structure: Do left/right features match when they should?

- Stability under rotation: Does it hold up from 8–12 viewpoints?

- Downstream success: Can you convert it into the representation you actually need?

If you only measure “looks good in one render,” you’ll ship disappointment.

People also ask: practical questions about Point‑E

Is a point cloud useful if I need CAD?

Yes, as a concept generator, not as CAD output. Treat it like an ideation artifact. If you need dimensioned, constraint-based CAD, you’ll still rebuild—but you’ll rebuild faster with a 3D draft in front of you.

Can Point‑E outputs be used in robotics training?

Often, yes—especially for domain randomization and synthetic data. If your goal is to expose policies to geometric variety, point-cloud-derived occupancy grids can be enough. For precision manipulation, you’ll need cleaner geometry and verified physical properties.

What makes a “good” text prompt for 3D generation?

Prompts work best when they specify structure, not poetry. Include shape cues, attachments, and constraints:

- Object category + key parts

- Material cues (optional)

- Symmetry or orientation (“front-facing,” “top handle”)

- Size hints (“handheld,” “tabletop,” “warehouse-scale”)

Example: a tabletop desk fan with a circular grille, three blades, a short cylindrical base, front-facing

Why Point‑E matters for AI-powered digital services in the U.S.

Point‑E is a reminder that the most valuable AI tools don’t need perfect outputs—they need to reduce cycle time. In the U.S. tech ecosystem, that shows up as services that generate 3D drafts for product teams, automate asset creation for retailers, and accelerate robotics simulation for automation pilots.

If you’re building in robotics & automation, the takeaway is straightforward: text-to-3D point clouds are a fast bridge between ideas and testable geometry. When your bottleneck is “we can’t model this fast enough to try it,” Point‑E-style systems change the pace of work.

The next step is deciding where you want the value: ideation, simulation, training data, or customer-facing visuals. Pick one, build a small pipeline around it, and measure time saved per iteration. What would your team ship if 3D prototypes were available in minutes instead of days?