Hand-eye calibration is the difference between AI perception and reliable picking. Learn Piper’s ROS 2 workflow, validation checks, and common pitfalls.

Piper Hand‑Eye Calibration That Actually Improves Picks

Most automation teams blame “the model” when a robot misses a grasp by 2–5 cm. The messy truth: a lot of those misses are calibration debt. If the robot doesn’t know where the camera really is relative to the end effector (or base), your perception stack can be brilliant and still point the gripper at the wrong place.

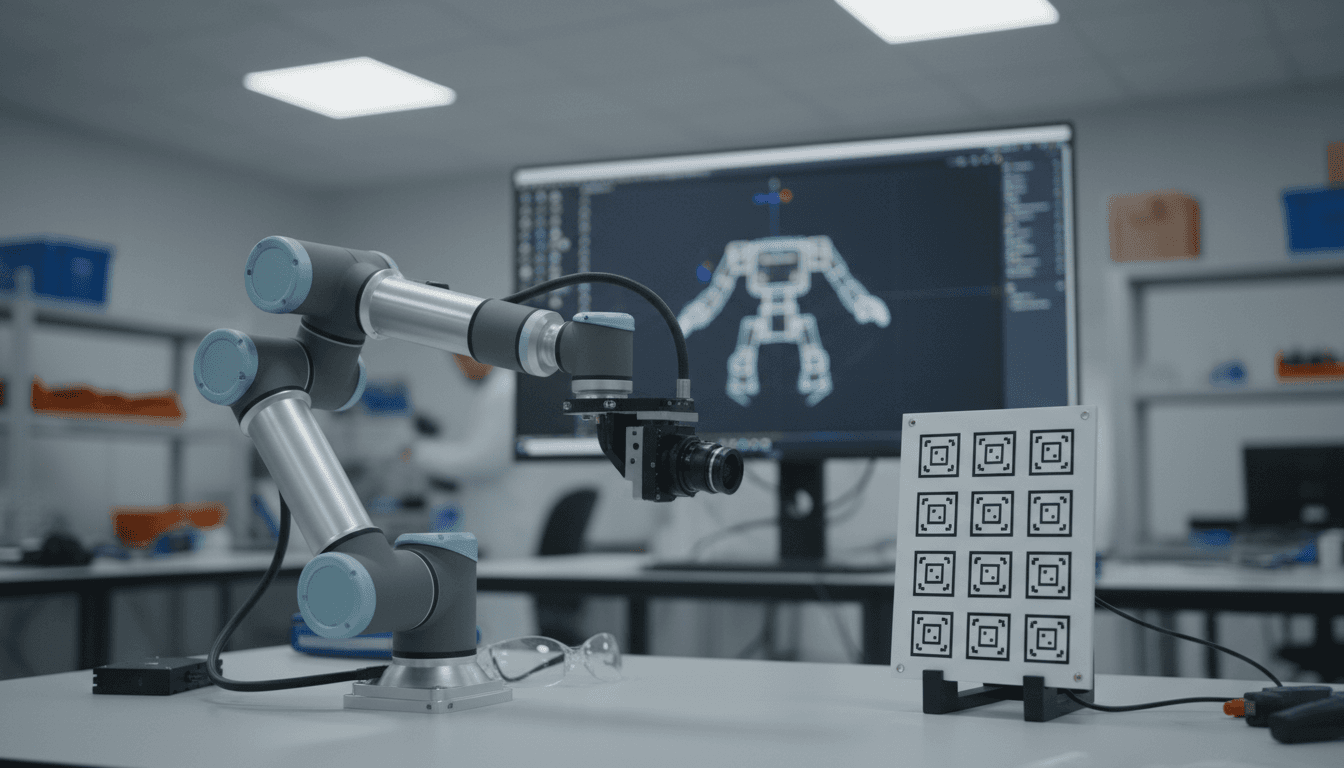

Hand‑eye calibration is the unglamorous step that turns AI perception into reliable robotic motion. In the AI in Robotics & Automation series, I keep coming back to this theme: AI adds intelligence, but geometry keeps you honest. This post breaks down Piper hand‑eye calibration (using ROS 2 and ArUco markers), explains when to use eye‑in‑hand vs eye‑to‑hand, and adds the practical checks that make the difference between “it ran once” and “it ships.”

Why hand‑eye calibration is the quiet driver of AI accuracy

Hand‑eye calibration aligns coordinate frames so your robot can act on what AI sees. Your perception system outputs a pose estimate in the camera frame. Your controller needs a pose in the robot base or end‑effector frame. The transform between those frames is the bridge.

When that bridge is off, everything downstream is off:

- Grasping and insertion: A 5 mm error at the flange can become a 15–30 mm miss at the fingertips depending on tool length and angle.

- AI training data quality: If you’re collecting demonstrations or auto‑labeling data with robot kinematics + vision, calibration error becomes label noise.

- Closed‑loop control: Visual servoing can “fight” a wrong transform, causing oscillations or slow convergence.

A snippet-worthy rule I use: Calibration is the difference between “AI can see” and “the robot can do.”

Eye‑in‑Hand vs Eye‑to‑Hand: pick the one that matches the workcell

The right setup depends on what moves: the camera, the target, or both. Piper’s workflow supports the two classic configurations.

Eye‑in‑Hand (camera on the robot)

Eye‑in‑hand is usually the best choice for grasping and bin-picking because the camera viewpoint follows the end effector.

- Camera is mounted on the end effector

- Calibration board is fixed in the environment

- You solve for the transform end effector → camera:

T_ee_cam

Then you can compute camera pose in base frame as:

T_base_cam = T_base_ee × T_ee_cam

Practical implication: once T_ee_cam is correct, you can move anywhere in the workspace and still get consistent camera-to-tool geometry.

Eye‑to‑Hand (camera fixed in the cell)

Eye‑to‑hand is often better for stable metrology, inspection, and positioning because the camera doesn’t move.

- Camera is stationary in the environment

- Calibration board is mounted on the end effector

- You solve for the transform base → camera:

T_base_cam

And you can compute end-effector to camera relationship as:

T_ee_cam = T_ee_base × T_base_cam

Practical implication: easier cable management and consistent lighting; harder to avoid occlusions around fixtures and parts.

A quick decision checklist

Use eye‑in‑hand if you:

- need to reach into clutter (bins, shelves)

- need flexible viewpoints

- want better coverage of poses for grasp planning

Use eye‑to‑hand if you:

- have a fixed conveyor or inspection station

- need repeatable camera extrinsics across many robots

- prefer simpler motion planning without camera mass on the wrist

The Piper ROS 2 calibration pipeline (what’s really happening)

Piper’s calibration flow is a practical “ROS-native” approach: publish poses from the robot and from the marker detector, then estimate the rigid transform that best explains the observations.

At a high level, you’re collecting synchronized pairs:

- Robot end-effector pose (from forward kinematics): typically

T_base_ee - Marker pose estimated in camera frame: typically

T_cam_marker

From many samples across different arm poses, the solver estimates the constant transform (T_ee_cam or T_base_cam) that minimizes error.

Prerequisites you actually need (and why)

From the source workflow, the core dependencies are:

- Ubuntu 22.04 + ROS 2 Humble: stable baseline for production ROS 2 deployments

- ArUco calibration board (generated with an online board generator): gives a robust, repeatable fiducial target

- ArUco marker detection package: produces marker pose from camera image + intrinsics

- Piper ROS package: publishes end-effector pose (

/end_posein the example) - Hand‑eye calibration node: consumes robot pose + marker pose and estimates extrinsics

- Camera intrinsics calibration (optional but commonly necessary): if your camera info is wrong, the marker pose will be wrong—no solver can fix that

Here’s my stance: don’t treat intrinsics as optional unless you’re using a camera driver that publishes accurate camera_info. If the intrinsics are off, you’ll chase phantom extrinsic problems for days.

Step-by-step setup (with the failure points called out)

The core steps are straightforward; the tricky part is topic wiring and data quality. The sequence below mirrors the Piper workflow and adds sanity checks.

1) Build a dedicated workspace

You create a workspace and clone three packages: marker detection, Piper driver, and calibration.

mkdir -p ~/handeye/src

cd ~/handeye/src

git clone -b humble-devel https://github.com/pal-robotics/aruco_ros.git

git clone -b humble https://github.com/agilexrobotics/piper_ros.git

git clone -b humble https://github.com/agilexrobotics/handeye_calibration_ros.git

Build:

cd ~/handeye

colcon build

Common failure point: building in a mixed ROS environment. If you’ve got multiple ROS installs, keep your shell clean and source only what you need.

2) Launch ArUco detection with the right board parameters

source ~/handeye/src/install/setup.sh

ros2 launch aruco_ros single.launch.py eye:=left marker_id:=582 marker_size:=0.0677

Two details must match reality:

marker_idmust equal the printed marker IDmarker_sizemust equal the physical marker size (meters)

If size is wrong by 10%, your translation estimates will be wrong by 10%. That’s not “a little noise.” That’s a guaranteed miss.

3) Run the camera driver and remap topics

Example shown with a RealSense node remapping to what the ArUco node expects:

ros2 run realsense2_camera realsense2_camera_node --ros-args \

-p rgb_camera.color_profile:=640x480x60 \

--remap /camera/camera/color/image_raw:=/stereo/left/image_rect_color \

--remap /camera/camera/color/camera_info:=/stereo/left/camera_info

Quality check: verify you have both image and camera info publishing. ArUco pose estimation needs intrinsics and distortion.

4) Bring up Piper and publish end-effector pose

bash ~/handeye/src/piper_ros/can_activate.sh

source ~/handeye/src/install/setup.sh

ros2 launch piper start_single_piper.launch.py can_port:=can0

Safety note (real-world cells): do first runs at low speed limits and confirm E-stop behavior. Calibration requires many poses; you don’t want surprises near fixtures.

5) Run the hand‑eye solver

ros2 run handeye_calibration_ros handeye_calibration --ros-args \

-p piper_topic:=/end_pose \

-p marker_topic:=/aruco_single/pose \

-p mode:=eye_in_hand

Choose eye_in_hand or eye_to_hand based on your setup.

6) Collect good samples (this is where results diverge)

Your calibration quality is dominated by pose diversity and detection stability. Piper’s guide suggests either teach mode or gamepad teleop. Either is fine, but here’s what matters:

- Capture 20–40 samples minimum for a first pass

- Vary position and orientation (don’t just move in a plane)

- Include rotations around multiple axes (roll/pitch/yaw coverage)

- Keep the marker well inside the image (avoid edge distortion)

If you only collect “fronto-parallel” views, your transform will look okay in one orientation and drift badly in others.

How to validate calibration before you trust it in automation

Validation is a separate step, not a vibe. Here are three checks that catch most issues.

1) Inspect the detection overlay

ros2 run image_view image_view --ros-args --remap /image:=/aruco_single/result

Look for:

- stable marker corners (no jitter)

- correct marker ID

- minimal blur (motion blur ruins corner localization)

2) Echo the marker and robot poses

ros2 topic echo /aruco_single/pose

ros2 topic echo /end_pose

You want smooth, believable values. If /aruco_single/pose jumps around centimeters while the camera is still, fix lighting/exposure or intrinsics first.

3) Do a “round-trip” sanity test

The fastest practical test: move the robot to 3–5 random poses and compute where the marker should be in the base frame using your calibrated transform. Then compare to the known physical location of the board.

If your board is fixed and measured (even roughly), you should see consistent residuals:

- < 5 mm: excellent for many pick-and-place tasks

- 5–15 mm: workable for coarse picks, not for tight inserts

- > 15 mm: something is wrong (intrinsics, marker size, sync, or frame conventions)

Don’t ignore orientation error, either. A few degrees of rotation error can ruin suction cups and insertion tasks.

Hand‑eye calibration in AI-driven automation: where it pays off

Better calibration directly improves the ROI of AI in robotics because it reduces the “mystery failures” that chew up engineering time.

Faster deployment of vision-guided picking

If your AI model detects a part pose at 30 Hz but your extrinsics are off, you’ll compensate with hacks:

- oversized grippers

- slow approach speeds

- manual offsets per SKU

A clean hand‑eye calibration reduces that need. It’s not glamorous, but it’s cheaper than endless tuning.

Cleaner data for learning-based manipulation

If you’re collecting demonstrations (teleop) or self-supervised grasp attempts, calibration affects labels like:

- grasp success position relative to object

- contact point estimation

- pose error metrics for training

Less label noise means models converge faster and generalize better.

More reliable simulation-to-real workflows

Gazebo and ROS-based simulation are foundational in AI robotics R&D, but sim-to-real breaks quickly when transforms are sloppy. A realistic pipeline is:

- Prototype perception and motion in simulation

- Bring up the same ROS 2 graph on the real robot

- Calibrate hand‑eye to anchor the real sensor to the real robot

- Validate with repeatable tests before scaling

That calibration step is the “anchor.” Without it, sim-to-real becomes guesswork.

Practical troubleshooting: the 6 issues that waste the most time

If calibration results look inconsistent, one of these is usually responsible:

- Wrong marker size: translation scale is wrong. Fix

marker_size. - Bad or missing camera intrinsics: pose estimates drift or jump. Ensure correct

camera_info. - Motion blur: corners are noisy. Increase lighting, reduce exposure, slow motion.

- Poor pose diversity: solution looks fine in one region, fails elsewhere. Sample broader orientations.

- Frame convention mismatch: transforms appear inverted/rotated. Verify which transform the node outputs (

T_ee_camvsT_cam_ee) and how you apply it. - Timestamp/synchronization issues: robot pose and image don’t correspond. Reduce latency, keep processing on the same machine, or log and post-process.

If you fix only one thing, fix intrinsics. I’ve seen teams spend a week on extrinsics when the camera was publishing a generic focal length.

Where to go next (and how to turn this into a deployable cell)

Hand‑eye calibration is a foundation block: once it’s solid, AI perception and planning start behaving like you expected from the beginning. For Piper users, the ROS 2 workflow with ArUco markers is a pragmatic baseline that’s easy to automate, repeat, and rerun after hardware changes.

If you’re building an AI-driven automation cell, the next step is to operationalize calibration:

- store the final transform in configuration (and version it)

- rerun calibration after any camera mount change, tool change, or collision event

- add a weekly “quick check” routine using a fixed board to detect drift early

The forward-looking question I’d ask your team: If you had to redeploy this workcell to a new site next month, could you repeat calibration in under an hour and get the same pick accuracy? If not, that’s the process gap worth fixing.