Performing robots reveal what service automation really needs: legible motion, safe collaboration, and adaptive AI. Learn practical lessons for 2026 deployments.

Performing Robots: What Dance Teaches AI Automation

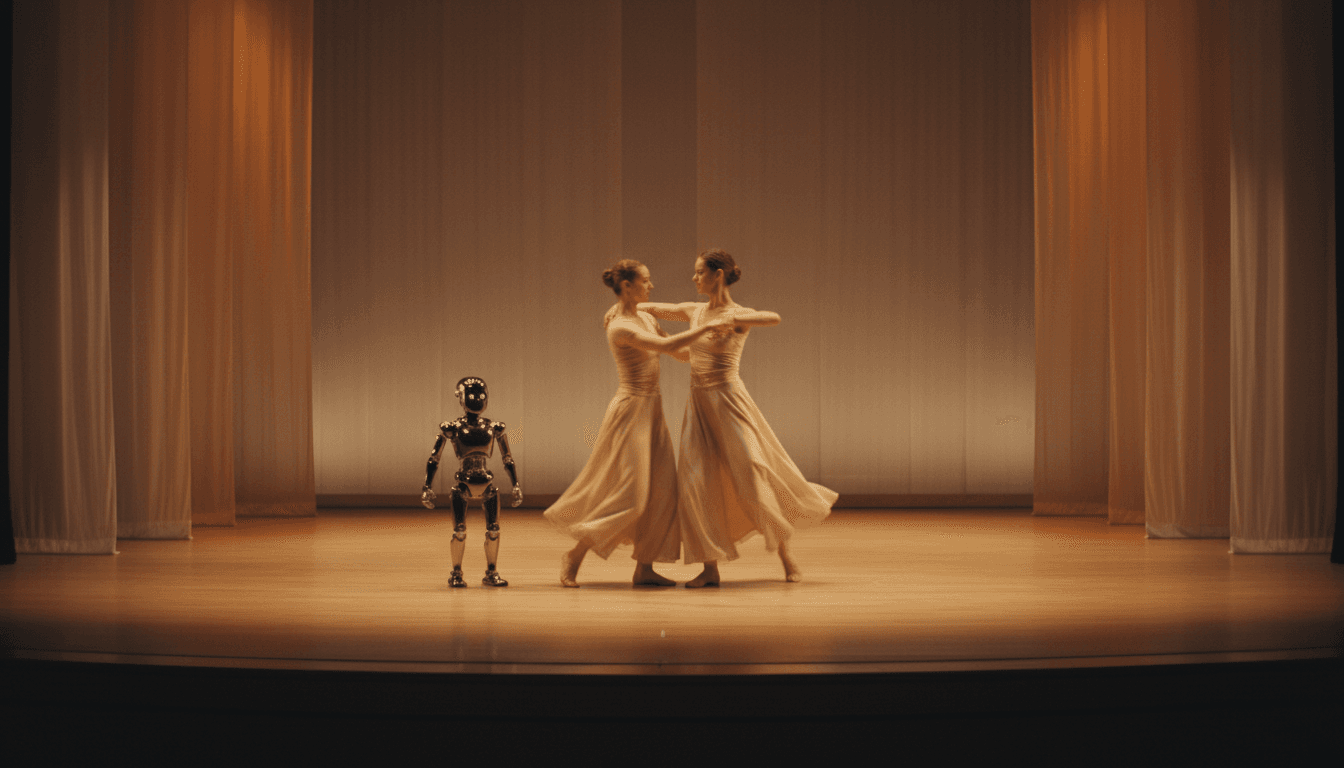

Most companies still talk about robots like they only belong on a factory floor—bolting parts, stacking pallets, welding frames. Meanwhile, robots are learning something far harder to fake: presence. They’re sharing a stage with humans, keeping time with music, adapting to partners, and communicating emotion through motion.

That’s why Robot Talk’s conversation with Amy LaViers—founder of the Robotics, Automation, and Dance (RAD) Lab and a builder of both choreographies and machines—matters to anyone working in AI in robotics and automation. Performing arts might sound “niche,” but it’s actually a stress test for service robotics: tight spaces, unpredictable humans, high expectations, and zero tolerance for clunky behavior.

If you’re evaluating intelligent automation for customer-facing environments (retail, healthcare, hospitality, museums, public venues), you can learn a lot from what it takes to put a robot on stage.

Robots on stage are a service-robotics masterclass

A robot that can perform alongside a dancer has to solve many of the same problems a service robot faces in the real world. The only difference is that the theater audience is paying attention.

In performing contexts, robots must operate under constraints that look a lot like real deployments:

- Human proximity: dancers move close, change pace, and improvise micro-adjustments.

- Timing and synchronization: the system must coordinate with music cues and human partners.

- Interpretability: people need to “read” the robot’s intent instantly from its motion.

- Safety without awkwardness: it can’t just stop constantly; it needs graceful fail-safes.

Here’s the stance I’ve come to after watching this space: performance is one of the most honest benchmarks for human-robot interaction. In manufacturing, you can fence the robot off and standardize everything. In the arts—and in service industries—you can’t.

Amy LaViers’ work sits right at that intersection: choreography as a design method, and robotics as a creative partner. That combination forces better questions than “Can the robot do the task?” It pushes you toward “Can humans comfortably work with it?”

Why dance is a better motion test than most labs

Dance looks subjective, but the engineering under it is brutally concrete. A movement either:

- hits the mark on time,

- reads clearly to a human observer,

- and stays safe in close contact,

…or it doesn’t.

Motion quality isn’t a luxury—it’s usability

In service environments, motion quality is UX. A mobile robot that navigates politely through a hospital corridor is doing choreography, whether you call it that or not.

On stage, “motion quality” becomes measurable. Choreographers care about:

- acceleration profiles (sudden jerks feel wrong and can feel unsafe),

- rhythm (humans track timing more than exact geometry),

- phrasing (movement grouped into meaningful units),

- pause and attention (stillness is also communication).

In automation projects, teams often optimize for path length or throughput and then act surprised when humans don’t trust the robot. Dance flips the priority: make intent legible first, then optimize.

Constraint-based creativity maps to real-world deployments

Performances rarely happen on perfect floors with perfect lighting and perfect markers. That’s valuable.

When choreographing robots, you design for constraints like:

- limited actuation and payload,

- imperfect sensing,

- battery limits,

- stage boundaries,

- changing human positions.

Those are the same constraints you’ll face when deploying AI-powered robotics in service settings. A museum guide robot, for example, has to feel responsive and calm even when its sensors are partially occluded by crowds.

Human–robot collaboration: the real point isn’t the robot

The headline might be “robots can dance,” but the deeper lesson is how humans coordinate with intelligent machines.

Amy LaViers emphasizes creative relationships between humans and machines. Translate that into business language and you get: shared control, role clarity, and trust calibration.

The most effective automation is co-performance

A lot of automation buying decisions still assume an either/or:

- either the human does it,

- or the robot does it.

On stage, that framing breaks. The goal is not replacement. It’s co-performance: each agent does what it’s good at.

In practical terms, that’s what modern automation looks like too:

- Humans set goals, handle exceptions, and read social context.

- Robots execute repeatable motion, keep tempo, and provide consistency.

- AI mediates perception, prediction, and adaptation.

A simple but useful rule: if your workflow requires social awareness, plan for a human-in-the-loop design from day one. Don’t bolt it on after the pilot fails.

Legibility beats “autonomy” in customer-facing spaces

In service robotics, autonomy is often oversold. What you actually need is behavior that people can predict.

Dance highlights a key principle from human-robot interaction research: legible motion—movement that communicates intent.

Examples outside the theater:

- A delivery robot that slightly “yields” at a crosswalk reads as polite.

- A cobot that slows as a worker approaches reads as considerate.

- A robotic arm that pauses at “decision points” reads as aware.

You can build sophisticated models, but if the robot’s motion is confusing, people will avoid it—or fight it.

The AI layer: from scripted moves to adaptive performance

Early performing robots often relied on scripted sequences. That’s fine for demos, but real value comes from adaptation.

The arts are pushing robotics toward what many companies want in 2026: embodied AI that can adjust behavior based on what’s happening around it.

What “adaptive choreography” looks like in robotics

Adaptive performance doesn’t mean the robot improvises randomly. It means the system can:

- Perceive human motion (vision, IMUs, proximity sensing).

- Predict near-term intent (where the dancer is going, when they’ll arrive).

- Plan a safe, expressive response (timed, smooth, bounded).

- Execute with stable control (no oscillation, no surprises).

That loop is the same loop you need in many service applications:

- a retail robot responding to aisle congestion,

- a hospital robot adapting routes during emergencies,

- an interactive kiosk robot changing posture and spacing when a child approaches.

The “stage” is a high-stakes simulation environment

There’s also a training-data angle. Performing arts environments create structured but human-rich scenarios:

- repeated rehearsals (great for iteration),

- consistent cues (music, lighting, marks),

- lots of human motion variety (great for robustness).

For teams building AI in robotics, rehearsal-like cycles are gold. You get rapid feedback on whether behavior is:

- safe,

- understandable,

- and emotionally “right.”

And yes—emotion matters. In service industries, your robot’s job often includes not annoying people.

What performing robots teach automation leaders (practical lessons)

If you’re leading an automation program, you don’t need to build a dancing robot to benefit from these insights. You can apply the same principles to warehouse AMRs, cobots, or customer-facing assistants.

1) Treat motion as part of the product

If your robot interacts with people, motion is not an engineering afterthought.

Action step: add a “motion review” to your acceptance criteria:

- Are starts/stops smooth?

- Does it slow early near humans?

- Can a non-expert predict what it will do next?

If you can’t answer those, you’re not ready for scale.

2) Pilot in spaces with real humans, not just test bays

Performance succeeds because rehearsal happens in context.

Action step: run pilots where your robot will actually work (even if limited hours), and measure:

- near-miss events,

- human avoidance behavior (do people step away or lean in?),

- time-to-completion and time-to-trust.

Trust shows up as reduced supervision, fewer manual overrides, and fewer “hovering” employees.

3) Design clear roles and handoffs

A dance duet works because roles are understood—lead/follow can switch, but the switching is choreographed.

Action step: document “handoff moments” in your workflow:

- When does the robot request help?

- What signals does it use (light, sound, posture, screen)?

- What happens if no one responds?

Most automation failures are handoff failures.

4) Optimize for legibility before throughput

Throughput is meaningless if people block the robot, disable it, or route around it.

Action step: when tuning navigation or arm motion, prioritize:

- consistent spacing,

- predictable yields,

- fewer sudden accelerations,

- visible intent signals.

Then optimize speed.

Why this matters now (December 2025)

As budgets reset and 2026 automation roadmaps get finalized, a lot of teams are looking beyond traditional manufacturing wins. The next wave of ROI is in service robotics: hospitals, labs, public infrastructure, entertainment venues, and retail back-of-house.

Performing robots are proof that robots can operate where humans are not trained operators—and where the environment isn’t perfectly controlled. That’s the exact direction the market is heading.

Amy LaViers’ career—bridging choreography, machine design, commercialization, and education—also points to something else: the winning robotics teams are cross-disciplinary. If you only hire for mechanical and ML, you’ll build capable machines that people don’t want near them.

If you’re mapping your next AI robotics pilot, borrow a theater mindset: rehearse in context, design for the audience (your staff and customers), and treat motion as communication.

Where could your automation program improve fastest if you judged your robots the way an audience judges a performance—by clarity, timing, and trust?