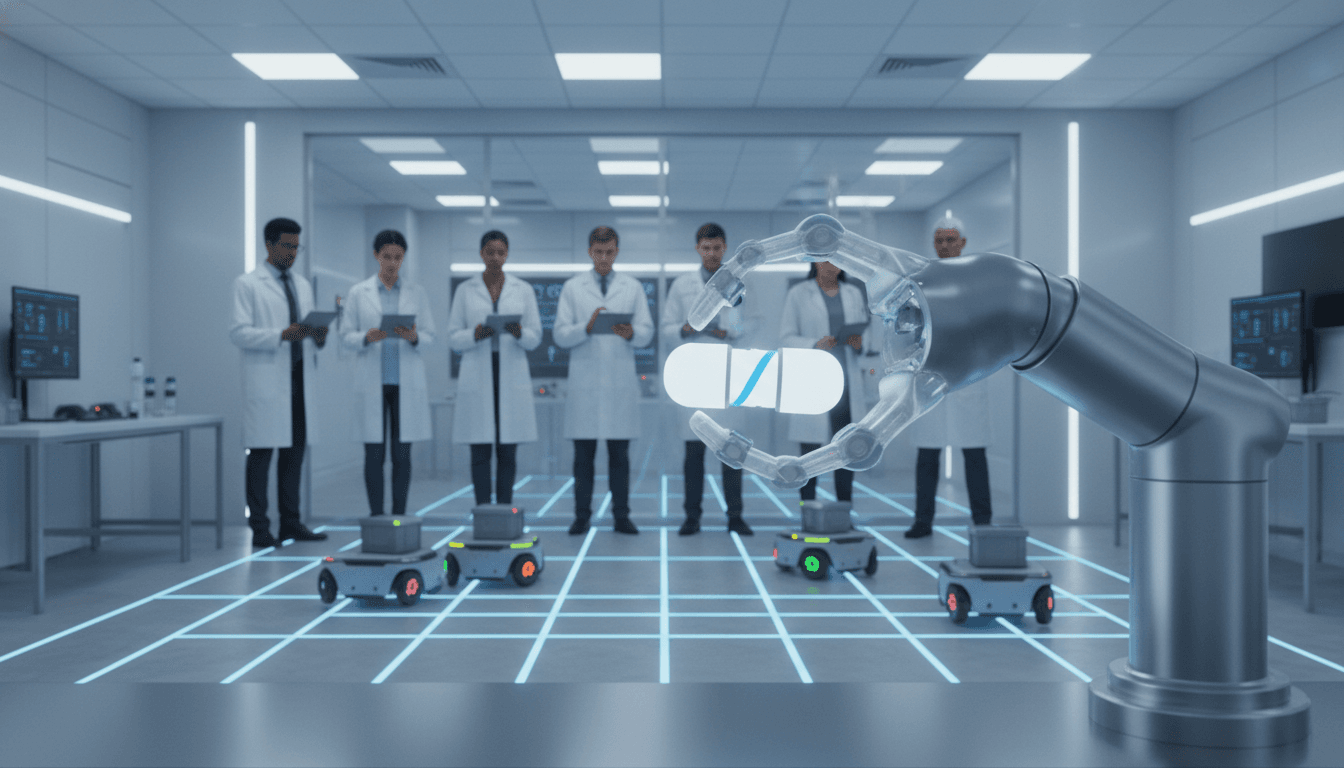

People-centered AI robots are winning in healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing. Learn practical lessons from MIT’s Daniela Rus for real-world deployment.

People-Centered AI Robots: Lessons From MIT’s Rus

Most robotics programs can build a robot that moves. Far fewer can build a robot you’d trust near a patient, an associate on a warehouse floor, or a technician on a production line.

That gap—between “it works in the lab” and “it works around people”—is exactly where people-centered robotics earns its keep. Daniela Rus, the longtime director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and a leader in what she calls physical intelligence, has built a career around a simple stance: robots should amplify human capability, not replace it. Her recent recognition with the IEEE Edison Medal puts a spotlight on a set of ideas that are increasingly practical for healthcare, logistics, and manufacturing teams evaluating AI-driven automation in 2026 planning cycles.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and I’m going to treat Rus’s work as a case study: not as biography, but as a playbook for building (and buying) robots that can actually be deployed.

People-centered robotics isn’t “soft”—it’s a deployment strategy

People-centered robotics means you design for the messy real world first: mixed environments, non-expert users, unpredictable objects, changing lighting, varying floor friction, human safety constraints, and business constraints like uptime and maintenance.

The practical takeaway: if your robot can’t handle variability, you don’t have an automation solution—you have a demo.

Rus frames robotics as “giving people superpowers,” and that’s a useful filter for evaluating any AI robotics initiative. Ask one blunt question:

- What human capability are we extending—and what risk are we reducing?

In industry, the strongest answers usually fall into three buckets:

- Reach: getting into places humans can’t (confined spaces, hazardous environments, inside the body, high shelves, high heat).

- Repeatability: performing the same action thousands of times with controlled variance.

- Responsiveness: sensing and acting fast enough to prevent errors, injuries, or downtime.

Rus’s lab work touches all three, which is why it maps cleanly to modern automation needs.

Physical intelligence: AI that understands force, friction, and failure

Here’s the core concept: physical intelligence is AI + embodiment + real-time decision-making under uncertainty. It’s not just perception (vision) and not just planning (maps). It’s the ability to cope when the world doesn’t match the training data.

This matters because many AI failures in robotics aren’t “model errors.” They’re physics errors:

- A gripper slips because the item’s coating changed.

- A wheel loses traction because the floor was recently cleaned.

- A robot arm collides because a human moved a cart into its path.

- A package deforms so the expected grasp point no longer exists.

People-centered design pushes teams to treat these as first-class requirements.

Why soft robotics keeps showing up in serious AI automation

Rus’s group builds soft-body robots inspired by nature, where materials and shape do part of the “computation.” That’s not a philosophical point—it’s an engineering advantage.

Soft systems can:

- Absorb uncertainty (compliance reduces precision requirements)

- Reduce risk around humans (less rigid-force interaction)

- Simplify control (the body stabilizes motion passively)

In manufacturing and fulfillment, this shows up as grippers that can pick a wider range of SKUs with fewer tool changes. In healthcare, it shows up as devices that can contact tissue safely.

The stance I’ve found most useful: when the environment is unpredictable, designing the body to be forgiving beats trying to “AI your way out” of every edge case.

Healthcare case study: ingestible robots and what they teach industry

Rus’s team developed ingestible robots that can retrieve foreign objects from the body (including swallowed batteries) and potentially deliver medication to targeted regions in the digestive tract. The details matter for anyone building or buying AI robotics, even outside medicine.

What makes this compelling as an automation pattern:

- The robot starts constrained (folded small enough to swallow)

- It navigates a highly variable environment

- It must be safe-by-design (biocompatible materials, controlled actuation)

- It uses a simple external control method (magnetic steering)

That’s a blueprint for high-stakes robotics: limit degrees of freedom, constrain failure modes, and choose interaction methods that are predictable.

A deployment lesson: “safe materials” is the physical-world equivalent of “safe prompts”

In enterprise AI conversations, people fixate on hallucinations and data leakage. In robotics, the equivalent risk is physical harm and uncontrolled contact.

People-centered robotics treats safety as:

- Mechanical safety (compliance, rounded geometry, limited force)

- Control safety (rate limits, safe-stop states)

- Operational safety (clear handoffs, training, maintenance routines)

If you’re evaluating robots for healthcare, food handling, or collaborative manufacturing, ask vendors for specifics:

- Maximum contact force and how it’s enforced

- Stop-time under load

- Failure state behavior (power loss, network loss, sensor faults)

- Cleaning/sterilization process and cycle impacts

From warehouses to factories: distributed robotics is about coordination, not charisma

Rus’s earlier work on teams of small robots cooperating on tasks fits the reality of logistics automation: the value is rarely one “hero robot.” It’s fleet behavior.

In warehouses and manufacturing intralogistics, coordination problems dominate:

- Task allocation (who does what)

- Congestion management (traffic control)

- Collision avoidance (safety + throughput)

- Exception handling (damaged items, blocked aisles, human interruptions)

The industry trend is clear: modern automation buyers are shifting from “how fast is one robot” to “how stable is the whole system during peak?”

What to copy: design the system like an adaptive network

Networked robots—like those used in large fulfillment operations—behave more like a distributed system than a machine.

That means your success metrics should look less like a spec sheet and more like operations:

- Orders per hour at peak (not average)

- Mean time to recovery after failures

- Exception rate per 1,000 picks/moves

- Operator interventions per shift

People-centered robotics forces you to measure the robot the way humans experience it: as a coworker that either creates calm or creates chaos.

The “no cloud required” push: why on-robot AI is becoming non-negotiable

Rus helped found a company in 2023 focused on adaptive neural network approaches intended to fit within hardware constraints. The bigger idea is what matters for automation leaders: put more intelligence on the robot.

In 2025–2026, this is showing up as a practical requirement in many RFPs, for three reasons:

- Latency: safety and control loops can’t wait on round trips.

- Reliability: Wi‑Fi dead zones shouldn’t stop production.

- Data governance: many facilities don’t want video and sensor feeds leaving the premises.

A straightforward procurement rule

If a robot’s core safety, navigation, or manipulation depends on persistent cloud connectivity, you’re buying operational risk.

A better architecture is usually hybrid:

- On-robot inference for real-time control

- Local edge services for fleet coordination and logging

- Cloud for analytics, model updates, and long-horizon optimization (when appropriate)

That setup matches how modern factories and warehouses actually operate.

How to evaluate “people-centered AI robotics” before you sign a contract

Here are five questions I’d put in front of any robotics vendor (or internal team) if the goal is real deployment in healthcare, logistics, or manufacturing.

1) What’s the variability budget?

Ask for the list of environment assumptions:

- Lighting range, reflectivity tolerance

- Floor conditions and slope limits

- Object variability (material, deformability, packaging changes)

- Human presence assumptions

People-centered teams know their limits and can explain them clearly.

2) Where does the system fail gracefully?

You want to hear specific safe states:

- What happens on sensor dropout?

- What happens on localization failure?

- What happens when the gripper can’t confirm a grasp?

A good answer describes behavior, not buzzwords.

3) How is the robot trained for your reality?

If the pitch is “pretrained model,” press harder:

- How much site data is needed?

- How is labeling handled?

- How long to reach stable performance?

- What monitoring catches drift?

4) What’s the human workflow?

People-centered robotics respects operators. Ask:

- Who resets the robot and how often?

- What does an exception look like?

- What training is required for new hires?

- What’s the escalation path at 2 a.m.?

5) What’s the total maintenance story?

Robots are physical products. Require details on:

- Preventive maintenance intervals

- Spare parts lead times

- Remote diagnostics capability

- Mean time to repair and who performs it

If any of these questions make the vendor uncomfortable, that’s your answer.

Where people-centered robotics is headed in 2026

Three shifts are accelerating right now:

- Soft manipulation becomes mainstream in picking, packing, and medical interaction because it reduces edge cases.

- On-robot AI grows up as compute gets cheaper and organizations tighten data policies.

- Human-robot interaction becomes a productivity feature, not a research topic—because adoption fails when people don’t trust the system.

Rus’s career arc is a reminder that the most valuable AI robotics work isn’t the flashiest. It’s the work that survives contact with humans, operations, and budgets.

If you’re planning an AI-driven automation initiative for the next 6–12 months, don’t start with “what robot should we buy?” Start with “what human capability should we extend safely?” Then build your requirements backward from that.

What would your operation look like if robots reliably handled the dull, dangerous, and disruption-prone work—while your team stayed in control of decisions that actually require judgment?