Light-powered ring robots climb wires and carry loads without batteries. See how AI boosts navigation, energy control, and inspection automation.

Light-Powered Ring Robots: Small Automation, Big AI

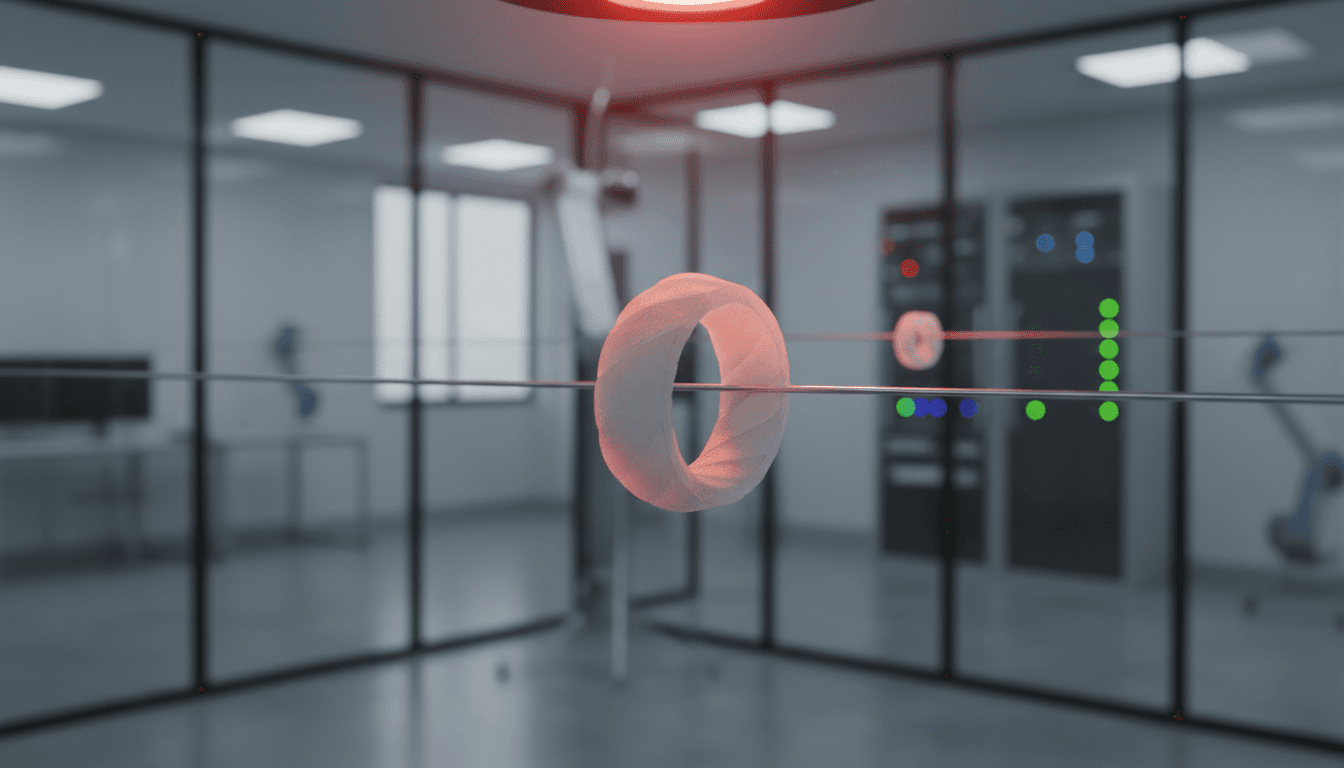

A soft robot made from a twisted ribbon can climb a wire at an 80° slope and haul a payload more than 12× its own weight—powered only by light. No batteries. No motors. No gears. Just a loop of material that contracts when it’s illuminated and “screws” itself forward like a tiny cable car.

That single demo (from a North Carolina State University team led by Assoc. Prof. Jie Yin) is more than a fun lab video. It’s a preview of where AI in robotics and automation is heading: smaller robots, simpler hardware, and smarter control. I’m increasingly convinced that the next wave of automation won’t always look like a six-axis arm in a cage. It’ll look like minimal mechanisms paired with maximal intelligence.

This post breaks down how the light-powered ring robot works, why it matters, and—most importantly—how AI can turn this kind of soft, micro-scale system into something deployable for inspection, maintenance, lab automation, and harsh environments.

What this light-powered ring robot actually is (and why that’s the point)

The key idea is almost annoyingly simple: replace complex electromechanical drivetrains with smart materials.

The “robot” is a looped ribbon of light-sensitive liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) with multiple twists, forming something like a rotini-shaped ring. When it’s hung on a track (wire, thread, or similar), the wire passes through two or three adjacent twists. The rest of the loop hangs below, and a small payload can be attached underneath.

When an overhead infrared (IR) light shines on the top section:

- The illuminated elastomer contracts.

- While contracting, the twisted geometry causes it to roll.

- That rolling acts like an auger/screw drive, pulling the ring along the track.

- As it moves, the ring continuously cycles “lit” material away from the light and brings “unlit” material into it, sustaining motion as long as illumination continues.

This matters because it flips a common robotics assumption:

If you can’t afford motors, sensors, and batteries at a tiny scale, you don’t stop—you redesign the robot so physics does more of the work.

In lab tests, variants of the ring robot moved along:

- Straight and curved tracks (including 3D curves)

- Track thicknesses from human-hair scale up to drinking-straw scale

- Obstacles like knots

- Slopes up to 80°

In other words: it’s a climber, a hauler, and a track-following delivery system—made from a single active material.

Why track-based micro-robots are showing up now

Track-following robots sound limiting until you compare them to the alternatives at small scale.

At centimeter and millimeter scales, robots hit ugly constraints:

- Batteries dominate mass and volume.

- Tiny motors are inefficient and fragile.

- Conventional wheels struggle on dust, moisture, and irregular surfaces.

- Vision and compute compete directly with power budget.

A track—wire, filament, tensioned line, routed thread, or even an existing cable—solves several of these at once:

- Guaranteed path (no roaming navigation needed)

- Stable traction (you always have a “rail”)

- Simpler safety model (keeps the robot away from sensitive surfaces)

- Predictable inspection coverage (great for maintenance)

That’s why track-based concepts keep reappearing in industrial automation: they’re boring in the best way.

The interesting leap here is actuation: instead of a motor-driven trolley, it’s a soft ring driven by light.

Where AI fits: turning a light-powered demo into a real automation tool

Here’s the thing about smart-material robots: the mechanism is elegant, but control can get messy fast. Light intensity, angle, distance, ambient temperature, payload mass, track friction, and curvature all affect speed and stability.

That’s exactly the kind of problem AI is good at—because you’re not trying to solve a perfect physics model; you’re trying to operate reliably under variation.

AI-driven energy control: “Just enough light” beats “more light”

The simplest way to run the robot is to blast IR at it and let it crawl. The practical way is to optimize illumination for:

- speed targets (deliver in 30 seconds, not “eventually”)

- payload safety (avoid overheating sensitive samples)

- energy cost (especially if illumination is battery-backed or solar-limited)

- consistency across changing conditions

A straightforward control stack could look like this:

- Sensing: basic photodiodes + temperature + timing feedback (even a single overhead camera can work in controlled settings)

- Model learning: a lightweight regression model or neural network predicts speed from light level, distance, slope, and payload

- Controller: a policy that sets light intensity and beam position to hit a speed/temperature constraint

In industrial terms, this is closed-loop control—but AI helps because the “plant” (soft material behavior) is nonlinear and drifts over time.

AI path planning: track networks are still networks

Even though the robot is constrained to a line, real deployments won’t be a single wire from A to B. They’ll be track networks with junctions, bypass routes, staging points, and “passing lanes.”

This is where classic robotics planning meets facility operations:

- Choose the fastest route vs. the lowest-energy route

- Schedule multiple robots to avoid congestion

- Decide when to reroute if a segment is contaminated or damaged

If you’ve ever done warehouse robotics, this will feel familiar—except the “roads” are suspended wires or routed filaments, and the “fuel” is directed light.

AI for task performance: inspection and delivery get smarter than motion

Motion is the easy part. The value comes from what the robot does while moving.

Track-following micro-robots become especially compelling when paired with tiny payload modules:

- a micro-camera for line-of-sight inspection along cable trays

- a small sensor package for temperature, humidity, VOCs, or radiation

- a micro-gripper or magnetic hook for carrying items between stations

AI adds capability without adding heavy hardware:

- Computer vision to detect corrosion, cracks, fraying, insulation damage

- Anomaly detection to flag “this doesn’t match baseline” on sensor streams

- Predictive maintenance to forecast failure risk on repeated passes

In other words, the robot doesn’t need to be physically complex if it’s operationally smart.

Practical applications that make sense (and a few that don’t)

The ring robot can climb steep slopes and handle obstacles like knots. That suggests a class of “overhead” or “off-surface” automation jobs where you want to avoid adding heavy infrastructure.

High-fit use cases

1) Cable, pipe, and rail inspection in hard-to-reach places

Facilities already have plenty of linear assets: wires, tension lines, guide cables, thin rails, and suspended supports. A robot that rides them could perform routine inspection without lifts or shutdowns.

2) Clean labs and micro-manufacturing delivery

In controlled environments, tracks can be purpose-built with predictable geometry. A light-driven robot can move samples between stations without onboard electrical noise or bulky batteries.

3) Temporary automation during outages or construction

A tensioned line can be installed quickly, used for weeks, then removed. That’s attractive when you need temporary transport/inspection without permanent conveyors.

4) Harsh or EMI-sensitive environments

Less onboard electronics can be a feature. If you can keep the robot mostly passive and drive it externally (light source offboard), you reduce failure modes.

Low-fit use cases (at least for now)

- General warehouse picking: too unconstrained, too many branches, too many interactions

- Outdoor deployment without robust sunlight operation: the current demonstration relies on IR illumination; sunlight introduces variability and thermal management challenges

- Heavy payload transport: 12× body weight is impressive, but absolute payload is still small

I’m a fan of being ruthless here: track robots win when the environment is linear and repeatable. If it’s not, you’ll spend more time forcing the problem to fit the robot than getting value.

Engineering realities: what needs to be solved before buyers care

The demo is exciting, but adoption depends on the unglamorous stuff.

Reliability and repeatability

Soft actuators can drift with:

- temperature cycling

- material fatigue

- surface contamination (dust/oils changing friction)

A deployable system needs calibration routines and health monitoring. AI can help by learning performance drift and adjusting illumination, but the platform still needs a defined maintenance schedule.

Traffic control and safety

If you deploy multiple units on shared tracks:

- you need spacing rules

- you need passing or pull-off areas

- you need a fail-safe state (what happens if the light goes out?)

A practical answer is to treat illumination as both propulsion and “permission.” No light, no motion. That’s inherently safer than a battery-powered device that can keep moving when you don’t want it to.

Standardized tracks and interfaces

In real automation, the track is part of the product:

- materials (wire/thread/rod) chosen for wear and cleanliness

- junction designs (switches) that don’t snag the robot

- docking points for loading/unloading payloads

If you’re thinking about commercialization, the track network is your infrastructure story, and the robot is only half the system.

How to evaluate a light-powered soft robot for your operation

If you’re an automation lead and you’re tempted by this class of system, here’s a practical checklist I use.

-

Is the job naturally linear?

Think “inspect along a run” or “move from station A to B,” not “navigate a room.” -

Can you tolerate external power delivery?

This approach assumes a light source (fixed or moving). That’s a design constraint, not a footnote. -

What’s the payload really?

Don’t look at “12× weight.” Look at grams, volume, and center-of-mass stability. -

What does failure look like?

If the robot stalls, can you retrieve it easily? Can it park at a safe point? -

Where does AI create measurable value?

Good answers include reduced inspection hours, fewer shutdowns, faster detection of anomalies, or consistent sample transport timing.

If you can’t answer #5 in numbers, it’s still interesting research—but it’s not a procurement project yet.

What to watch next: sunlight operation and smarter autonomy

The research team has already hinted at adapting the ring robot to respond to sunlight or other energy sources. That’s the milestone that changes the deployment story.

- Sunlight-capable actuation opens outdoor infrastructure inspection (think lines, spans, and suspended runs).

- Multi-source actuation (light + heat + magnetic fields, for example) could create redundancy and better control in variable environments.

- AI scheduling and optimization turns single-robot demos into fleet operations—where most automation ROI actually lives.

The broader theme in this “AI in Robotics & Automation” series is that intelligence increasingly shows up where hardware is constrained. This light-powered ring robot is a clean example: the mechanism is minimal, the environment is structured, and AI can do the heavy lifting—navigation logic, energy management, anomaly detection, and operational planning.

If you’re building automation roadmaps for 2026 budgets, this is the right mental model: simple bodies, smart systems, and infrastructure-aware deployment. The next question is a practical one—where in your facility could a track-based robot remove a recurring manual task without adding a whole new maintenance headache?