Industrial robodogs like the Lynx M20 bring AI inspection to harsh sites. Learn where they fit, what to validate, and how to pilot for ROI.

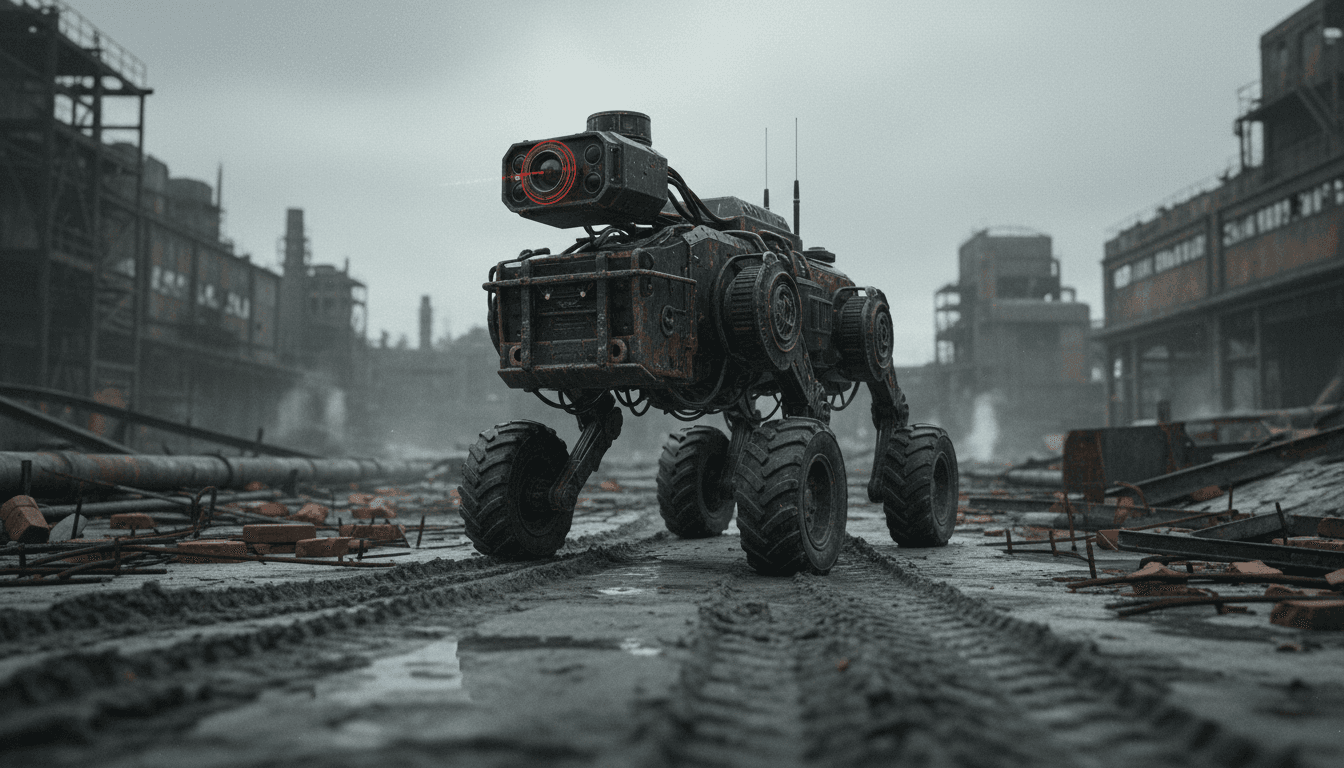

Industrial Robodogs: AI Inspection in Extreme Sites

A 33‑kg robot that can squeeze through a 50‑cm gap, climb 80‑cm obstacles, and work from -20 °C to 55 °C isn’t a novelty—it’s a very practical answer to a problem most industrial teams are tired of paying for: sending people (or fragile machines) into places that are risky, remote, dirty, or simply hard to reach.

Deep Robotics’ Lynx M20 is a rugged, wheeled quadruped built for industrial extremes: IP66 sealing, hot‑swap batteries, and a sensor stack designed for navigation and teleoperation in ugly conditions. For our AI in Robotics & Automation series, this is a strong signal: industrial robotics is shifting from “can the robot move?” to “can the robot reliably do work where operations actually happen?”

What I like about this category—industrial “robodogs”—is that they force a clearer conversation. Not “should we buy a cool robot,” but which inspections, patrols, and logistics runs can be automated next quarter, and what data will we capture while doing it?

Why rugged robodogs are showing up on real job sites

Rugged quadrupeds are being adopted because they reduce exposure and stabilize operations in environments that punish humans and standard robots. That’s the whole point. If a facility has stairwells, gravel, sand, puddles, debris, tight corridors, or harsh weather, wheels alone struggle, legs alone can be slower, and humans get tired or put at risk.

The Lynx M20’s design choice—wheels plus legs—isn’t a gimmick. It’s a productivity decision:

- Wheels handle long corridors and flat stretches quickly (reported 7.2 km/h operating, up to 18 km/h max).

- Legs handle steps, gaps, and uneven terrain.

- Wheel locking enables “walk mode” and controlled climbing.

This matters because industrial automation rarely fails in the lab. It fails in the first month onsite when a robot meets the real world: wet floors, dust, cramped clearances, inconsistent lighting, and operators who don’t have time to babysit it.

The real industrial pain this solves

Robotic mobility becomes valuable when it targets repetitive, measurable work:

- Infrastructure inspection: tunnels, bridges, substations, plants, industrial yards

- Disaster and emergency response: debris, unstable structures, hazardous atmospheres

- Logistics and distribution edge cases: outdoor yards, mixed indoor/outdoor routes, temporary structures

- Scientific research and remote monitoring: harsh terrain where you still need high-quality data

Robodogs don’t replace skilled technicians. They change what technicians spend time on: fewer miles walked with clipboards; more time diagnosing, planning, and fixing.

What makes the Lynx M20 “industrial” (and not just athletic)

Industrial robots are defined less by stunts and more by uptime, sealing, serviceability, and sensing. The Lynx M20 checks several of the boxes that typically separate a demo robot from a deployable platform.

Environmental hardening: IP66 and wide temperature range

If you’ve ever tried running sensors in dust or driving electronics through thermal swings, you know why these numbers matter:

- IP66: dust-tight and protected against powerful water jets

- -20 °C to 55 °C operating range

Those are practical thresholds for many outdoor sites, winter maintenance windows, hot industrial yards, and emergency deployments.

Mobility specs that translate to site coverage

The M20 is reported to:

- Fit through 50 cm gaps

- Climb obstacles up to 80 cm

- Handle inclines up to 45°

These aren’t bragging rights; they’re route-enablement. A robot that can’t reliably clear a standard stair or debris lip becomes a robot that operators stop trusting.

Payload and power: where “robot platform” becomes “robot worker”

A 15‑kg payload is enough for many industrial sensor packages:

- thermal camera + visible camera

- gas detector module

- acoustic/ultrasound payloads for condition monitoring

- additional compute or comms equipment

The 2.5–3 hours per charge is workable if missions are planned well—and the hot‑swap battery design is what makes it operational instead of precious. In industrial deployments, you don’t want “charge downtime” to be a scheduling bottleneck.

The AI stack behind ‘autonomy’: LiDAR, SLAM, and navigation

The biggest value of an industrial robodog isn’t that it can walk; it’s that it can build spatial context, navigate safely, and return consistent data. That’s where AI in robotics earns its keep.

The Lynx M20 includes a 96‑line LiDAR providing 360° situational awareness, plus a wide-angle front camera and lighting for low-visibility operation and remote viewing. On the “Pro” variant, Deep Robotics lists:

SLAMpositioning and mapping- autonomous navigation

- autonomous charging

- connectivity upgrades (USB, Gigabit Ethernet)

Why SLAM is the workhorse feature

SLAM sounds academic until you put a robot in a plant where:

- GPS is unreliable or unavailable

- layouts change (pallets, barriers, temporary equipment)

- lighting varies (glare, shadows, night operations)

A strong SLAM pipeline helps a quadruped do three critical things:

- Repeat routes (patrol the same corridor daily and compare results)

- Localize (know where it is when the environment isn’t ideal)

- Map changes (flag new obstacles or blocked passages)

Here’s a stance I’ll defend: repeatability is more valuable than full autonomy in most industrial settings. A robot that reliably runs 80% of a mission every day and produces consistent inspection data will beat a “fully autonomous” robot that succeeds 95% of the time but fails unpredictably.

Teleoperation still matters—and it’s not a failure

Even with advanced navigation, industrial teams want human override for exceptions. The Lynx M20’s lighting and live video feed support that reality.

A good deployment plan assumes:

- autonomy for standard routes

- teleop for edge cases

- clear procedures for handoff (who takes control, when, and how)

That combination is how you scale robots without pretending you’ve removed humans from the loop.

Where industrial robodogs fit in automation (with concrete use cases)

Industrial robodogs are best deployed where mobility + sensing replaces routine human travel, not skilled judgment. Below are four high-ROI patterns I’ve seen teams succeed with.

1) “First pass” inspection rounds

Give the robot a scheduled route: perimeters, corridors, stairwells, and critical assets. It captures thermal + visual imagery, plus LiDAR context.

Good fits:

- substations and switchyards

- water and wastewater plants

- cement, mining, and aggregate sites

- warehouses with outdoor yards

Why it works: it reduces routine walking and improves consistency. A robot doesn’t “forget” to check the far corner.

2) Post-incident reconnaissance

After an alarm, leak, storm, or minor structural incident, the first need is often: eyes on scene without putting people at risk.

A rugged robodog that can traverse mud, debris, or wet floors can provide:

- quick visual confirmation

- thermal hotspots

- route viability for responders

3) Remote sites and “dark” operations

In late 2025, more operations teams are being asked to do more with less: fewer night shifts, fewer miles driven, more remote oversight. Robots can support that trend by acting as mobile sensor nodes.

Pair the robot with:

- a docking/charging strategy

- alert thresholds (thermal anomalies, unexpected obstacles)

- exception-based human review

4) Hybrid logistics in messy environments

AMRs are excellent on flat indoor floors with well-managed traffic rules. Many sites don’t have that luxury.

A wheeled quadruped can cover:

- temporary construction areas

- mixed gravel/asphalt yards

- short-haul outdoor transport with obstacles

It won’t replace high-throughput conveyors or fleets of AMRs. But it can fill the gap where automation usually gives up.

Buying checklist: what to validate before you pilot

A robodog pilot succeeds when you define the mission, the data, and the recovery plan—not when you start with a wow video. If you’re evaluating an industrial quadruped like the Lynx M20, validate these items early.

Mission clarity (the part most teams skip)

Write down:

- Route length and terrain types (stairs, ramps, gravel, puddles)

- What “done” looks like (photos of X assets, thermal scan of Y panels)

- Frequency (daily rounds, weekly inspection, incident response)

If you can’t describe the mission in one paragraph, you’re not ready to pilot.

Data and integration requirements

Ask how you will:

- store and label imagery/telemetry

- compare results over time (trend analysis)

- integrate with CMMS/EAM workflows (work orders and maintenance logs)

A robot that collects data without a pipeline becomes an expensive camera operator.

Operational resilience

Confirm:

- battery swap time and spares strategy

- cleaning and maintenance procedures (IP66 helps, but sensors still need care)

- network plan (Wi‑Fi, private LTE/5G, dead zones)

- “what happens when it fails” playbook (safe stop, operator takeover, retrieval)

Safety, security, and governance

Quadrupeds raise understandable concerns. Treat them like industrial machines, not toys:

- geofencing and access controls

- audit logs for teleop sessions

- secure update process

- clear policies for cameras in sensitive areas

If your security team isn’t in the room early, you’ll lose momentum later.

The bigger trend: rugged robots are becoming the new edge compute platform

Robodogs are turning into mobile edge systems: sensors + compute + autonomy + connectivity on legs. That’s why they’re relevant to AI-driven automation beyond “inspection.”

As AI models get better at anomaly detection (thermal irregularities, corrosion patterns, leaks, obstructed paths), the robot’s job shifts from “record everything” to record what matters and escalate what’s urgent. That’s where leads and ROI tend to show up: fewer false alarms, faster response, more predictable maintenance.

The Lynx M20 is a good example of the direction the market is moving—toward robots that can handle dirt, water, heat, and rough terrain while still supporting modern autonomy features like SLAM and navigation.

If you’re building an AI in Robotics & Automation roadmap for 2026 budgeting, rugged quadrupeds belong on the shortlist for any operation with outdoor exposure, stairs, tight spaces, or safety constraints.

A simple rule: if your technicians carry a flashlight, a radio, and a camera on routine rounds, a robodog is a serious candidate.

Most teams don’t need “full autonomy.” They need reliable robotic coverage and a clean path from robot data to maintenance action.

If you’re considering a pilot, start with one route, one asset class, and one outcome metric. Then scale.

Where could a robot safely replace the travel part of your inspections—so your experts can focus on the fixes?