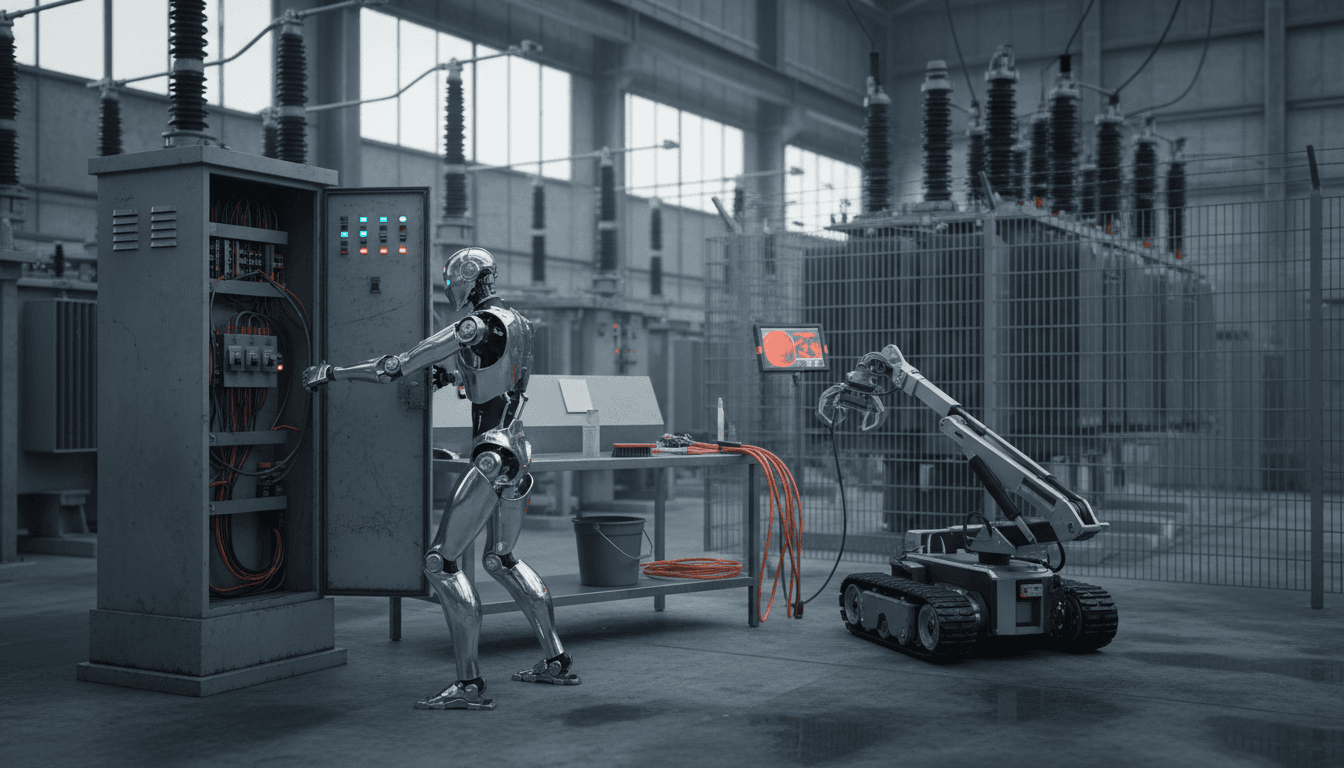

Humanoid robot challenges reveal what’s missing for real utility maintenance: force control, tool use, wet handling, and unedited autonomy.

Humanoid Robot Challenges That Matter in Utilities

Most humanoid robot “competitions” still reward the wrong skills. Punching, kicking, and carefully staged demos look impressive, but they don’t tell you whether a robot can handle the messy, forceful, repetitive work that keeps critical infrastructure running.

Benjie Holson’s “Humanoid Olympics” concept gets closer to the truth: robots become genuinely useful when they can manipulate the real world with consistency—doors, laundry, tools, and wet cleaning. If you work in energy and utilities, that should sound familiar. Your hardest automation problems aren’t about recognition or planning in isolation; they’re about doing: turning stiff valves, opening corroded cabinets, aligning connectors, wiping down contaminated surfaces, and completing multi-step maintenance without constant human rescue.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and it’s a practical one. We’ll translate the Humanoid Olympics into a utility lens: what these tasks reveal about modern robot learning, why “laundry folding” doesn’t equal “field maintenance,” and how to evaluate robotics + AI programs that actually reduce outages and truck rolls.

Why manipulation benchmarks beat spectacle

Answer first: The best robotics benchmarks resemble real work: variable conditions, asymmetric forces, and “no edits.” That’s why manipulation challenges are a better predictor of real-world value than staged athletic demos.

A utility environment is basically an obstacle course built by time:

- Fasteners seize, housings deform, gaskets swell, and labels fade

- Surfaces get oily, wet, dusty, or ice-cold

- Tasks are high-stakes: a slip can break a connector, arc a contact, or contaminate an enclosure

- Access is constrained: tight cabinets, awkward reach, bad lighting, PPE constraints

Holson’s events (doors, tools, fingertip manipulation, wet manipulation) force robots to handle the same fundamentals:

- Forces that aren’t symmetric (twist + pull, press + stabilize)

- Objects that deform (cloth, sponges, bags, cables)

- Precision under load (align a key, press a spray trigger, peel an orange)

- Whole-body coordination (getting through a door without losing the handle)

Those fundamentals map cleanly to utility tasks like opening switchgear doors, operating breakers, cleaning insulators, manipulating hose couplers, using inspection tools, and servicing pumps.

The real state of the art: learning from demonstration (and its limits)

Answer first: Today’s most reliable general-purpose manipulation comes from learning from demonstration—teleoperating a robot hundreds of times, then training a model to imitate those trajectories.

Holson describes a common workflow: a human teleoperates via VR or a “twin robot” puppeteering setup, records 10–30 second snippets hundreds of times, and trains a neural network to reproduce them. This works well when:

- The task has many valid micro-motions (cloth unfolding, towel corner pulling)

- The environment is “structured enough” (similar starting layouts, known objects)

- You can tolerate medium precision (often ~1–3 cm end-effector accuracy in many teleop-driven demos)

Why utilities feel harder than laundry

Utility work adds two pain points that the “folding videos” often avoid:

- Force and contact are the job. Turning a stiff knob, seating a connector, or cracking loose a corroded latch demands force control, not just geometry.

- Failure recovery matters. In the field, you don’t reset the scene after a slip. The robot has to re-grasp, re-align, or change strategy.

Holson also calls out four constraints that matter directly for energy and utilities:

- No high-resolution force feedback at wrists (hard to teach “how hard” to push or twist)

- Limited finger control (many hands are closer to “open/close” than true dexterity)

- No robust sense of touch (humans rely on tactile cues constantly)

- Medium precision (fine alignment remains difficult without specialized sensing/control)

If you’re evaluating robotics vendors for maintenance automation, these are the questions to ask early, not after a pilot stalls.

Translating the “Humanoid Olympics” into utility-ready capabilities

Answer first: Each event is a proxy for a class of utility tasks—access, tool use, fine manipulation, and contamination-safe cleaning.

Below is a practical mapping you can use to sanity-check whether a humanoid or mobile manipulator is trending toward field utility.

Event 1: Doors → Access to cabinets, yards, and enclosures

Doors sound trivial until you meet asymmetric forces: twist hard, pull gently, don’t slip, then move your whole body through the opening.

Utility equivalent tasks:

- Opening substation control house doors (often self-closing)

- Accessing pad-mounted transformer cabinets

- Swinging open switchgear doors while managing cables/hoses

What “good” looks like:

- Handle/lever actuation without regrasping three times

- Maintaining contact while the door fights back (springs, closers)

- Whole-body motion that doesn’t yank the handle off-axis

My stance: If a robot can’t open a self-closing pull door reliably, it’s not ready to operate in a yard without constant babysitting.

Event 2: Laundry → Deformables are everywhere (cables, hoses, PPE)

Laundry is the poster child for deformable manipulation because cloth has a huge state space. Utilities have their own “laundry,” just less photogenic:

- Handling cables and leads during inspection or temporary bypass

- Managing hoses for washdown or sampling

- Handling gloves, wipes, absorbent pads, and protective covers

The point isn’t folding shirts; it’s building representations and policies that cope with objects that:

- Change shape while you hold them

- Hide their own important features (edges, openings)

- Become slippery, wet, or snaggy

If your roadmap includes robotic cleanup, containment, or cable management, deformables are a leading indicator.

Event 3: Tools → The bridge from “demo” to “work order”

Tool use is where general-purpose manipulation becomes operationally meaningful.

Holson’s examples (spray bottle + paper towels, making a sandwich, using a key) highlight three tool truths:

- Tools require stable grasps under torque

- Tools require regrasping and in-hand adjustment

- Tools require intentional force application (pressing triggers, scraping, turning)

Utility equivalents:

- Using an IR thermometer, ultrasound probe, or inspection camera

- Operating a grease gun, sealant applicator, or manual pump primer

- Turning panel keys, unlocking cabinets, engaging disconnects (where permitted)

A practical evaluation checklist for tool-readiness:

- Can it pick up a tool from a cluttered surface?

- Can it adjust grip without putting the tool down?

- Can it apply repeatable force (not just “attempt”)?

- Can it complete a multi-step sequence autonomously?

Event 4: Fingertip manipulation → Connectors, fasteners, and small controls

Rolling socks, opening a dog bag, peeling an orange—these sound silly until you consider what they proxy:

- Separating thin layers (bag opening → tape, liners, protective films)

- Pinching and sliding with precision (orange peel → seals and gaskets)

- Maintaining delicate grasp while applying localized force

Utility equivalents:

- Aligning and seating multi-pin connectors

- Handling zip ties, clips, O-rings, and small covers

- Working toggle switches and small rotary controls

This is the realm where tactile sensing and high-bandwidth force control stop being “nice to have.” They’re the difference between an automation success and a broken connector.

Event 5: Wet manipulation → The honest test for real maintenance

Wet manipulation is the fastest way to reveal whether a robot is designed for real environments or lab conditions.

Holson’s wet tasks (wiping with a sponge, cleaning peanut butter off the manipulator, washing grease off a pan) map cleanly to utility realities:

- Cleaning oil/grease from components before inspection

- Washdown after contamination events

- Working around condensation, rain, snow melt, or standing water

The hidden requirement is not just waterproofing. It’s grasp stability when friction changes and perception when glare and droplets distort vision.

If a system can’t tolerate wet work, you’ll end up restricting deployments to the easiest 20% of sites—the ones you didn’t need robotics for in the first place.

What utilities should borrow from the “no-cuts, time-boxed” rules

Answer first: The best robotics procurement questions are procedural: “Show me unedited autonomy, in real time, with a time budget.”

Holson’s rules are sharp: autonomous completion, real-time video, no cuts, and a time cap (up to 10× human time). Utilities can adapt that into a vendor evaluation standard that prevents “pilot theater.”

Here’s a version I’ve found works in practice:

- No edits, no resets. Record a continuous run from start state to completion.

- Define a time budget. If a human does it in 2 minutes, give the robot 10–15 minutes. Not 2 hours.

- Specify success criteria. “Valve fully seated to torque range,” “panel latched,” “surface visibly clean.”

- Include variability. Two different cabinet types, two lighting conditions, one wet surface.

- Score recovery. A slip isn’t an automatic fail if the robot recovers without human touch.

This approach also pairs well with AI programs utilities already run. The same discipline used in grid optimization—clear metrics, baselines, and repeatable tests—should apply to robotics.

Where AI for grid optimization meets AI for manipulation

Answer first: Both grid AI and robot AI fail for the same reason: they look great in controlled data and struggle at the edges—rare events, shifting conditions, and feedback delays.

Learning from demonstration in robotics mirrors supervised learning in utility analytics:

- You collect examples (teleop trajectories or historical SCADA/AMI data)

- You train models to imitate patterns

- You discover the model struggles when conditions drift

The difference is that manipulation adds physics: contact, force, friction, compliance, and wear. That’s why the path forward in utilities will likely be hybrid:

- Foundation models for perception and high-level sequencing (what to do next)

- Classical control + force control for stable contact behaviors

- Tactile sensing to replace the “human feel” that’s missing in teleop

- Simulation + real-world data for scaling without breaking hardware

If you’re building a roadmap, prioritize the stack that closes the loop on contact: wrist force/torque sensing, tactile arrays, and controllers that can regulate force as confidently as position.

Practical next steps for utility leaders considering robotics

Answer first: Start with tasks that are repetitive, high-risk for humans, and measurable—and demand autonomy evidence under realistic conditions.

A sensible sequencing looks like this:

- Inspection assistance first: mobile manipulation to position sensors, open simple latches, hold tools

- Light intervention next: wipe-downs, label placement, filter swaps, basic cleaning (wet manipulation “bronze”)

- Tool workflows after: repeatable tool use with force limits and verification steps

- High-consequence operations last: fine connectors, keyed access, torque-critical actions

And don’t skip the operational plumbing:

- Who “owns” exception handling at 2 a.m.?

- How are tasks authorized and logged for compliance?

- What’s the fail-safe state if perception degrades?

- How do you prove the robot did the required step (photos, sensor readings, torque logs)?

These questions sound boring. They’re also where deployments succeed or die.

A simple rule: If a robot can’t show unedited, autonomous recovery from small errors, it won’t survive real maintenance work.

Where this is headed in 2026 (and why that matters)

Robotics is entering a phase where the demos will get prettier—and that can be misleading. The organizations that win won’t be the ones chasing the flashiest humanoid video. They’ll be the ones building systems that can reliably do three unglamorous things: access, manipulate with force, and clean up after themselves.

For energy and utilities, the opportunity is straightforward: the same AI discipline you apply to reliability—metrics, baselines, drift monitoring, and operational accountability—should shape your robotics strategy. When manipulation capability improves, it won’t just make warehouse robots nicer. It will directly reduce outages by enabling faster inspection, safer maintenance, and earlier intervention on failing equipment.

If a humanoid can open a self-closing pull door, use tools without fumbling, and handle wet cleanup without falling apart, it’s no longer a toy. It’s a field asset. Which utility task would you want it to prove first?