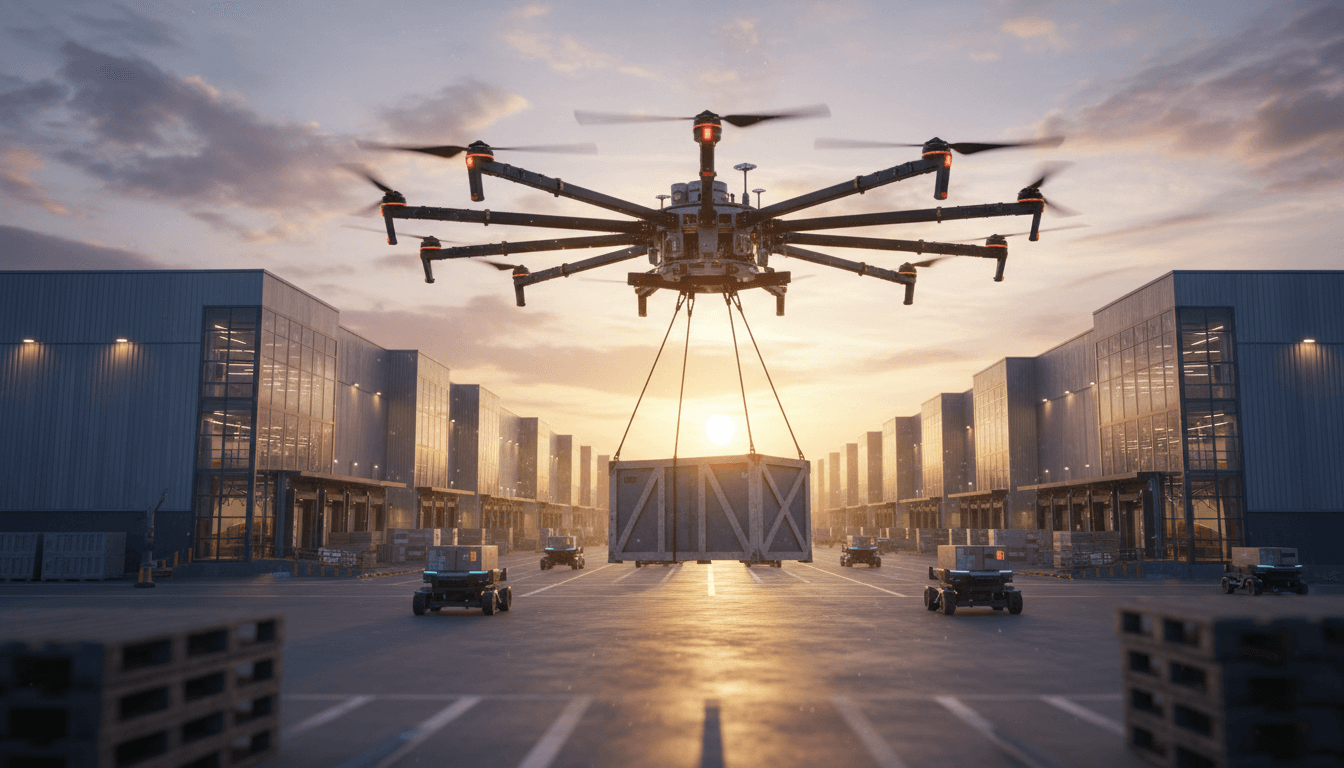

Heavy-lift drones that carry 4x their weight are moving from demos to industrial logistics. See the AI stack, use cases, and buyer questions to pilot safely.

Heavy-Lift Drones: The Next Leap in AI Logistics

A typical multirotor drone can lift about as much as it weighs. That 1:1 payload-to-weight ratio is the quiet constraint behind most “cool demo” drone videos never becoming real operations.

DARPA’s Lift Challenge is blunt about what needs to change: build drones that can carry payloads more than four times their own weight. If teams start hitting that mark consistently, heavy-lift drones stop being a niche aircraft category and become something logistics leaders can actually plan around—especially in places where forklifts, conveyors, and docks can’t reach.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and I’m going to take a stance: the real breakthrough isn’t just stronger airframes—it’s autonomy you can trust while you’re moving expensive, bulky loads. Heavy lift without AI is a stunt. Heavy lift with AI becomes infrastructure.

Why heavy-lift drones matter for industrial automation

Heavy-lift drones matter because they change where “automation” is possible. Warehouses and factories are already automated inside the building. The mess starts outside: yards, laydown areas, job sites, remote depots, disaster zones, and temporary peak-season staging. That’s where fixed automation breaks down.

When a drone can lift 4x its own mass, it becomes a flying material-handling tool. Think less “last-mile package delivery,” more:

- Just-in-time parts movement between buildings on a campus without trucks

- Moving tooling, totes, and kits across large yards where pedestrians and vehicles conflict

- Feeding temporary production lines during facility reconfigurations

- Rapid resupply for maintenance crews in wind farms, mines, and rail corridors

And because it’s December 2025, this lands at the right time. Peak season pressures don’t disappear after the holidays; they usually leave behind a backlog of “we need resilience next year” projects. Heavy-lift drones slot directly into that planning.

The hidden bottleneck: it’s not lift, it’s repeatability

Yes, motors and props matter. But in industrial settings, the bigger issue is repeatable mission execution:

- Pick up the right load

- Verify the load is secure

- Fly a safe route that respects geofences and dynamic obstacles

- Land precisely, every time

- Hand off the payload without damaging goods, infrastructure, or people

That’s an AI problem—specifically perception, planning, anomaly detection, and control under uncertainty.

What DARPA’s Lift Challenge is really signaling

DARPA’s involvement is a market signal: heavy-lift autonomy is strategically important. When an agency puts a challenge behind a constraint like payload-to-weight ratio, it’s not just chasing performance—it’s trying to pull an ecosystem forward.

Here’s what I read between the lines:

- Novel aircraft designs are welcome. Expect unusual configurations, hybrid rotor systems, ducted fans, variable pitch, or designs optimized around specific payload geometries.

- The use cases aren’t limited to defense. Industrial logistics will benefit first because the ROI math is simpler: reduce labor, reduce vehicle movements, increase uptime.

- Autonomy will be a differentiator. A heavy-lift drone that requires expert pilots and perfect weather is hard to scale. A drone that can operate safely with minimal human babysitting becomes an asset class.

Heavy-lift capability without autonomy increases operational complexity. Heavy-lift capability with autonomy reduces it.

That’s the inversion most companies miss.

The AI stack that makes heavy-lift drones operational

The practical question buyers should ask is: what AI capabilities reduce daily friction? Not “does it have AI,” but “which failure modes does AI prevent?”

Below is the stack I’ve found most useful for evaluating real deployments.

Perception: seeing loads and risks in the real world

Heavy-lift drones don’t get clean, lab-like environments. They get:

- reflective shrink wrap

- dusty laydown yards

- rain on sensors

- swinging loads

- people who walk where they shouldn’t

Perception needs to cover:

- Payload identification and pose estimation (what is it, where is it, how is it oriented?)

- Landing zone assessment (flatness, debris, slope, wind effects)

- Dynamic obstacle detection (people, vehicles, cranes, other drones)

The trend we’re seeing across robotics—including in aerial–ground robot research using language+vision hierarchies—is a push toward vision-first autonomy that can run with fewer specialized sensors. That’s attractive for cost and maintenance, but only if the system is engineered for harsh edge conditions.

Planning and control: carrying a load changes everything

A heavy payload shifts the drone’s dynamics:

- center of gravity moves

- inertia increases

- wind sensitivity increases

- failure tolerance decreases

So planning isn’t just “go from A to B.” It’s:

- trajectory planning under load constraints

- contingency planning (where do you divert if the landing zone becomes unsafe?)

- stability control with disturbance rejection

This is where AI and classical control have to work together. Pure learning-based control can be brittle. Pure classical control can be blind to context. The teams that win operationally tend to blend both.

Safety intelligence: the difference between a demo and a deployment

Industrial adoption depends on predictable safety behavior. That means the drone needs to detect and respond to “bad days”:

- battery underperformance in cold weather

- partial motor degradation

- unexpected payload swing

- GPS denial or multipath issues

- sudden wind gusts near structures

AI is increasingly used for health monitoring and anomaly detection—spotting subtle deviations before they become incidents. This is not flashy, but it’s what makes insurance, compliance, and site managers comfortable.

Where heavy-lift drones fit alongside other robots

Heavy-lift drones won’t replace warehouse AMRs or conveyors. They fill the gaps between them.

Look at the current direction of robotics in logistics:

- AMRs acting as “virtual conveyors” inside facilities

- mobile manipulators doing flexible pick and place

- quadrupeds and mixed fleets operating in semi-structured environments

Heavy-lift drones complement that stack by handling verticality and distance. They’re especially good when the alternative is a human driving a vehicle for a short, repetitive run.

A realistic near-term workflow

Here’s a workflow that’s plausible in 2026–2027 at many industrial sites:

- An AMR consolidates totes at a pickup point.

- A heavy-lift drone autonomously verifies the tote ID and weight.

- The drone flies to a secondary building or remote staging pad.

- Another robot (or a human) completes the final placement.

The AI glue is coordination: scheduling, traffic management, and exception handling. And that’s exactly where automation projects tend to succeed or fail.

What to ask vendors before you pilot heavy-lift drones

If your team is exploring heavy-lift drones for industrial logistics, skip the glossy payload number and ask questions that reveal operational maturity.

1) What payload-to-weight ratio is achievable in real conditions?

Ask for performance under:

- wind thresholds (site-specific)

- temperature ranges

- altitude/density effects

- repeated duty cycles (not one-off lifts)

A drone that can lift 4x its weight once is interesting. A drone that can do it 30 times per shift is a business tool.

2) How does the system validate a safe pickup?

You want specifics:

- load engagement confirmation

- weight estimation vs. expected weight

- swing detection and mitigation

- abort behavior if attachment is imperfect

3) What autonomy level is real, and what still needs a skilled operator?

There’s nothing wrong with supervised autonomy, but you need to know:

- how many drones per operator

- what triggers human intervention

- how often those triggers occur in similar deployments

4) What’s the plan for compliance and site safety integration?

Industrial drone programs live or die on process:

- geofencing

- flight approvals

- incident logging

- integration with site access controls

5) How is AI monitored after deployment?

If the drone uses vision and learning-enabled components, ask:

- how model drift is detected

- how updates are validated

- what on-site data is stored and how it’s governed

That last part matters a lot in regulated industries and unionized environments.

The business case: where ROI shows up first

The fastest ROI shows up where you’re paying for motion, not work. In other words: labor and vehicles moving items that don’t require human judgment.

Heavy-lift drones can reduce:

- short-haul vehicle trips in large facilities

- time lost to yard congestion

- delays moving urgent parts to maintenance teams

- exposure to hazards (traffic, weather, uneven terrain)

They can also improve resilience. When a route is blocked, a drone can reroute in minutes without needing new infrastructure.

If your logistics problem is “we need a conveyor,” drones are the wrong tool. If your problem is “we need material flow where we can’t justify a conveyor,” drones are a strong candidate.

What happens next (and how to prepare)

DARPA’s Lift Challenge is pushing the hardware bar up, but the bigger shift is what it enables: AI-powered aerial material handling as a normal part of automation architecture.

If you’re leading robotics or operations strategy, the best next step isn’t buying a drone tomorrow. It’s doing three pieces of groundwork now:

- Map your “non-conveyable” flows: where do items move outside buildings, across yards, or between sites?

- Define payload classes: weight, dimensions, attachment method, damage sensitivity.

- Plan your autonomy boundaries: where do you require human-in-the-loop, and where are you comfortable with supervised autonomy?

As this AI in Robotics & Automation series keeps emphasizing, the winning play is rarely a single robot. It’s a fleet of systems that handle exceptions gracefully. Heavy-lift drones are about to become one of the most useful pieces of that puzzle.

If you could move one category of material through your operation without trucks or forklifts, what would you move first—and what would that change downstream?