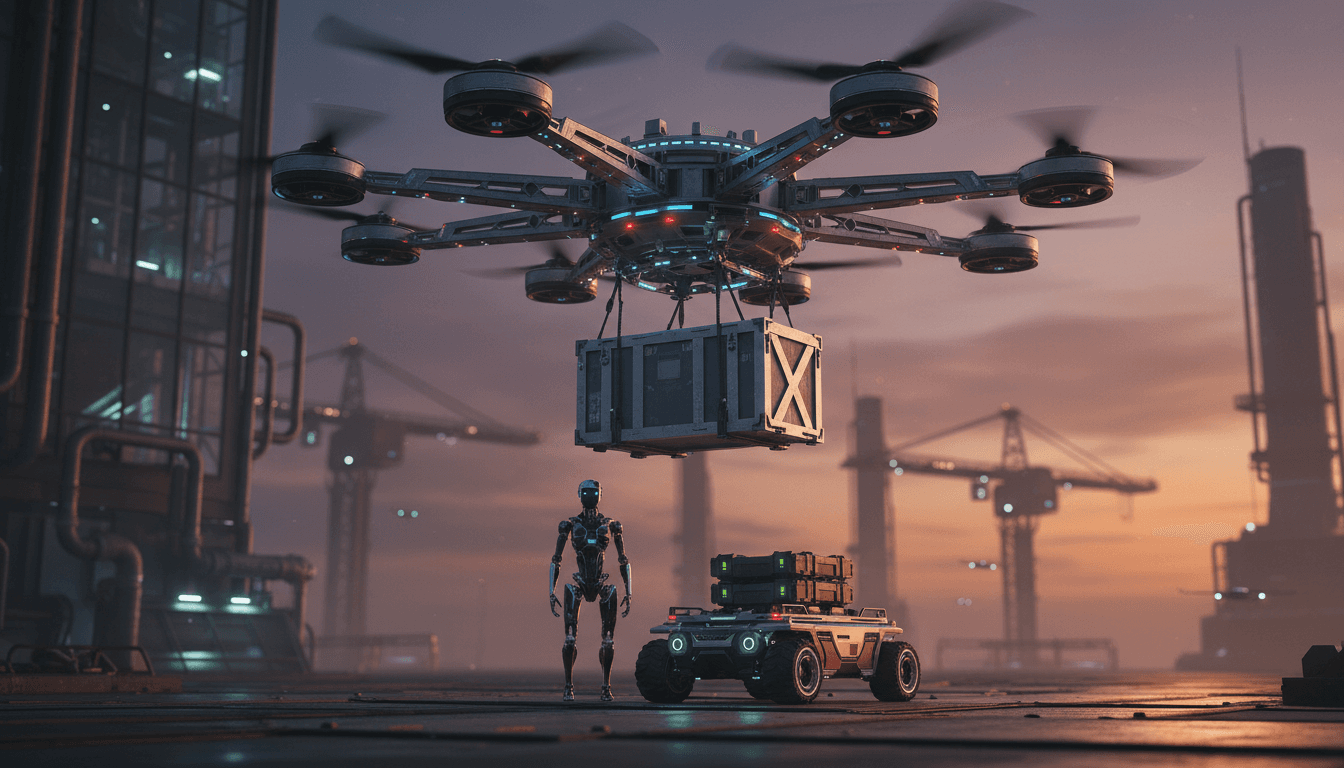

Heavy-lift drones, scalable humanoids, and AI control models are reshaping logistics, manufacturing, and agriculture. Here’s what to track for 2026.

AI Robots to Watch: Heavy-Lift Drones to Humanoid Scale

A payload-to-weight ratio of 1:1 is where most multirotor drones hit the wall. That’s fine for cameras and sensors, but it’s a hard stop for the jobs businesses actually want: moving parts across a yard, lifting tools onto rooftops, or hauling supplies in a disaster zone. DARPA’s Lift Challenge is swinging at that wall with a clear target—drones that can carry payloads more than 4× their own weight.

That one number matters because it hints at a broader shift happening across robotics right now. We’re watching robots graduate from “clever demos” into repeatable work: warehouses using “virtual conveyor” robots to keep orders flowing, vineyards deploying mobile manipulators to handle delicate produce, and research labs pushing language + vision control so robots can operate longer without constant reprogramming.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and the theme is simple: AI is turning robots into adaptable workers, not just specialized machines. Here’s what this week’s set of robotics videos signals for anyone planning automation in logistics, manufacturing, or agriculture—and what I’d do next if I were evaluating these systems for real operations.

Heavy-lift drones: the 4× payload race is really an autonomy problem

The headline is “carry 4× your weight,” but the real story is control and safety. As soon as you push beyond a 1:1 payload-to-weight ratio, you’re no longer tuning a hobby-grade multirotor. You’re managing a system where small errors compound fast: thrust margins shrink, battery sag becomes mission-critical, and stability under load turns into the primary constraint.

Why payload-to-weight ratio changes the economics of drone automation

For industrial drone operations, payload capacity is the ROI lever. A drone that can lift heavier loads doesn’t just do more per flight—it can replace a class of equipment.

Here’s how the math typically plays out:

- More payload means fewer trips and fewer battery swaps

- Fewer trips means fewer operator interventions and lower risk exposure

- Heavier payload enables new workflows: tools, parts, medical supplies, or sensors that were previously ground-only

The “4× payload” target is aggressive enough to trigger step-function use cases:

- Construction and maintenance: lifting tools, anchors, cables, or small components to elevated work sites

- Intralogistics outdoors: moving totes or parts between buildings where fixed conveyors don’t make sense

- Emergency response: delivering heavier medical kits, portable comms, or power modules

What AI actually does for heavy-lift drones

Most companies shopping for drones focus on airframes and batteries first. That’s understandable—and also where projects go sideways.

AI helps in three practical ways:

- Adaptive control under changing loads: a heavy-lift drone needs controllers that can handle payload swing, shifting centers of gravity, and aerodynamic disturbances.

- Perception for safe operations: obstacle avoidance isn’t optional when you’re carrying heavier objects over people or property.

- Planning and compliance: route planning, geofencing, and mission logging are where industrial drone programs become scalable (and insurable).

Snippet-worthy truth: Heavy lift is less about motors and more about trust—trust that the robot will stay stable, predictable, and auditable.

If you’re leading automation in logistics or industrial sites, I’d treat heavy-lift drones as a systems engineering purchase, not a “drone purchase.” Your success depends on the autonomy stack as much as the hardware.

Humanoid robots at scale: shipping hundreds is a manufacturing signal

Seeing hundreds of humanoid robots delivered in one batch (as highlighted by UBTECH’s Walker S2 shipment) is more than a flashy milestone. It’s a sign that humanoids are crossing into a new phase: repeatability in production and deployment.

Why scale matters more than a single impressive humanoid demo

A single humanoid doing a single task tells you almost nothing about whether it will survive a real facility.

Scale tells you three things that buyers should care about:

- Supply chain maturity: can they build the same robot again and again with consistent tolerances?

- Serviceability: do they have the parts pipeline, diagnostics, and repair workflows to keep uptime reasonable?

- Deployment discipline: are they shipping a platform with a plan, or a prototype with a marketing budget?

Humanoids still aren’t the default answer for most automation programs. For many workflows, a mobile base with a simple arm will beat a biped on cost and reliability. But humanoids are gaining traction where environments are built for humans: stairs, narrow aisles, mixed tooling, and ad-hoc tasks.

The AI layer that will make—or break—humanoid ROI

The hard part isn’t getting a humanoid to walk. The hard part is getting it to do useful work without a robotics PhD babysitting it.

That’s why the momentum around behavioral foundation models and promptable control (more on that below) is so relevant. The winner won’t be the company with the fanciest gait—it’ll be the company that makes task creation fast:

- “Pick items from this bin and place on that cart.”

- “Tighten these fasteners to spec.”

- “Restock this station when inventory drops below X.”

When those instructions become reliable and auditable, humanoids stop being a curiosity and start being a staffing strategy.

Warehouse automation is shifting from fixed infrastructure to flexible robots

Saddle Creek’s deployment of Robust.AI’s Carter as a “virtual conveyor” is a preview of where many warehouses are heading: less bolted-down automation, more adaptable material flow.

“Virtual conveyor” is a practical idea with big operational benefits

Conveyors are great—until your process changes.

A robot that shuttles totes between multiple lines and 20+ drop-off points can be valuable even if it’s not deeply integrated into every system. That “non-integrated” detail matters: it lowers adoption friction.

The operational wins tend to look like this:

- Faster reconfiguration when SKUs, packaging, or labeling steps change

- Better utilization across multiple lines (robots can be re-tasked)

- Lower capex risk compared to installing new fixed infrastructure

Where AI fits in warehouse robots (beyond navigation)

Navigation is table stakes now. The real differentiators are:

- Dynamic dispatching: deciding which tote should move next, based on line congestion and downstream constraints

- Exception handling: recognizing damaged totes, blocked lanes, or mis-scans and escalating appropriately

- Human-aware behavior: safely operating in tight spaces with mixed pedestrian traffic

If you’re evaluating warehouse robotics, ask vendors how they handle these three areas. A robot that drives from A to B is nice. A robot that keeps throughput stable during chaos is what you actually need.

Aerial–ground teams and language–vision control: autonomy that lasts longer than a demo

One of the most promising research directions in this roundup is the aerial–ground robot team using a language–vision hierarchy to achieve long-horizon navigation and manipulation on a UAV + quadruped using only 2D cameras.

Why “long-horizon” autonomy is the benchmark that matters

Robots don’t fail in the first 30 seconds. They fail at minute 12—when lighting changes, when a door is half-open, when the target object isn’t where it was yesterday.

Long-horizon autonomy means the robot can:

- Maintain task context across time

- Recover from mistakes without a full reset

- Coordinate between platforms (air finds, ground fetches; or ground scouts, air verifies)

That combination is exactly what real industrial and field operations look like.

The practical case for UAV + ground robot teams

Paired systems can be more reliable than one “do everything” robot.

- UAVs are great for rapid situational awareness and inspection

- Ground robots are better for carrying tools, manipulating objects, and operating longer

Put them together and you get workflows like:

- Yard and perimeter inspection: UAV identifies anomalies; ground robot investigates and reports

- Asset localization: UAV maps and tags; ground robot retrieves or stages items

- Agriculture scouting + action: aerial survey spots issues; ground unit performs targeted intervention

For buyers, the key question is integration: can the autonomy stack share maps, tasks, and safety constraints across platforms without turning your operation into a custom software project?

Behavioral Foundation Models for robots: fewer retrains, more reuse

BFM-Zero’s premise—learning a shared latent space that embeds motions, goals, and rewards so one policy can be prompted for multiple downstream tasks—aligns with where the whole industry is heading.

What a Behavioral Foundation Model (BFM) is, in plain terms

A BFM is a generalist control policy trained to cover a wide range of behaviors so you can prompt it for new tasks instead of retraining from scratch.

Think of it as the difference between:

- Programming a new robot behavior every time you change the job

- Giving the robot a base “skill library” and instructing it using higher-level goals

Why this matters for manufacturing, logistics, and agriculture

Most automation programs stall on the same problem: every new SKU, package, or station layout becomes a new integration cycle.

BFMs don’t remove engineering work, but they can reduce it in the places that cost the most:

- Task adaptation

- Edge cases

- Mixed environments where you can’t fully standardize

Snippet-worthy truth: The robots that win won’t be the ones that can do one task perfectly. They’ll be the ones that can do 30 tasks well enough—and learn the 31st fast.

If you’re planning a robotics roadmap for 2026, foundation-model-style control is a capability to track closely, especially for humanoid robots and mobile manipulators.

Field robots and mobile manipulators: vineyards, farms, and “how mobile is mobile?”

The roundup also highlights practical robotics work across agriculture and mobile manipulation: grape-picking robots, a featured mobile manipulation platform (MOMO), and the evergreen question from Clearpath Robotics: how mobile does your mobile manipulator need to be?

A simple rule for picking the right form factor

If you’re automating physical work, the form factor decision often comes down to one constraint:

- If the environment is structured and repeatable, simpler robots win.

- If the environment is messy and changing (farms, mixed warehouses, multipurpose facilities), adaptability wins.

Agriculture is the poster child for “messy and changing.” Fruit size varies, foliage occludes, terrain shifts, and weather changes lighting constantly. That’s why AI perception (vision, grasp planning, and quality detection) matters so much.

What to ask before investing in AI-driven field robotics

I’ve found that buyers get better outcomes when they pressure-test three things early:

- Harvest or handling quality metrics: bruising rate, missed picks, contamination risk

- Uptime model: what happens when a sensor fails mid-row or connectivity drops?

- Changeover time: how long to adapt from one variety/block/pack spec to another?

Robots in agriculture and outdoor logistics don’t need to be perfect—they need to be predictable, serviceable, and economically sensible.

What this week’s robotics lineup says about 2026 automation plans

Three patterns show up across heavy-lift drones, humanoids, warehouse shuttlers, and research platforms.

First: capability is moving from hardware novelty to operational readiness. Shipping robots in volume and deploying them in real fulfillment flows is a stronger signal than any lab demo.

Second: AI is becoming the unifying layer—from language–vision hierarchies that extend autonomy duration to behavioral foundation models that reduce retraining.

Third: the best automation programs in 2026 will be hybrid. Expect teams of robots (aerial + ground), robots plus humans, and flexible systems that can be reconfigured without ripping out infrastructure.

If you’re building a robotics pipeline for logistics, manufacturing, or agriculture, the next step is to assess where your bottlenecks are:

- Is it payload and physical capability (heavy lift, manipulation strength)?

- Is it adaptation (new SKUs, new tasks, layout changes)?

- Is it orchestration (dispatching, exception handling, safety in mixed traffic)?

Answer that honestly, and you’ll know whether to prioritize heavy-lift drone programs, warehouse “virtual conveyors,” mobile manipulators, or foundation-model-driven humanoids.

The forward-looking question I keep coming back to: when your robots can be prompted like software, what work will you stop building fixed infrastructure for?