Generalizing from simulation is how robotics AI trained virtually stays reliable in the real world. Learn methods, pitfalls, and a practical checklist.

Generalizing From Simulation: AI Robots That Work IRL

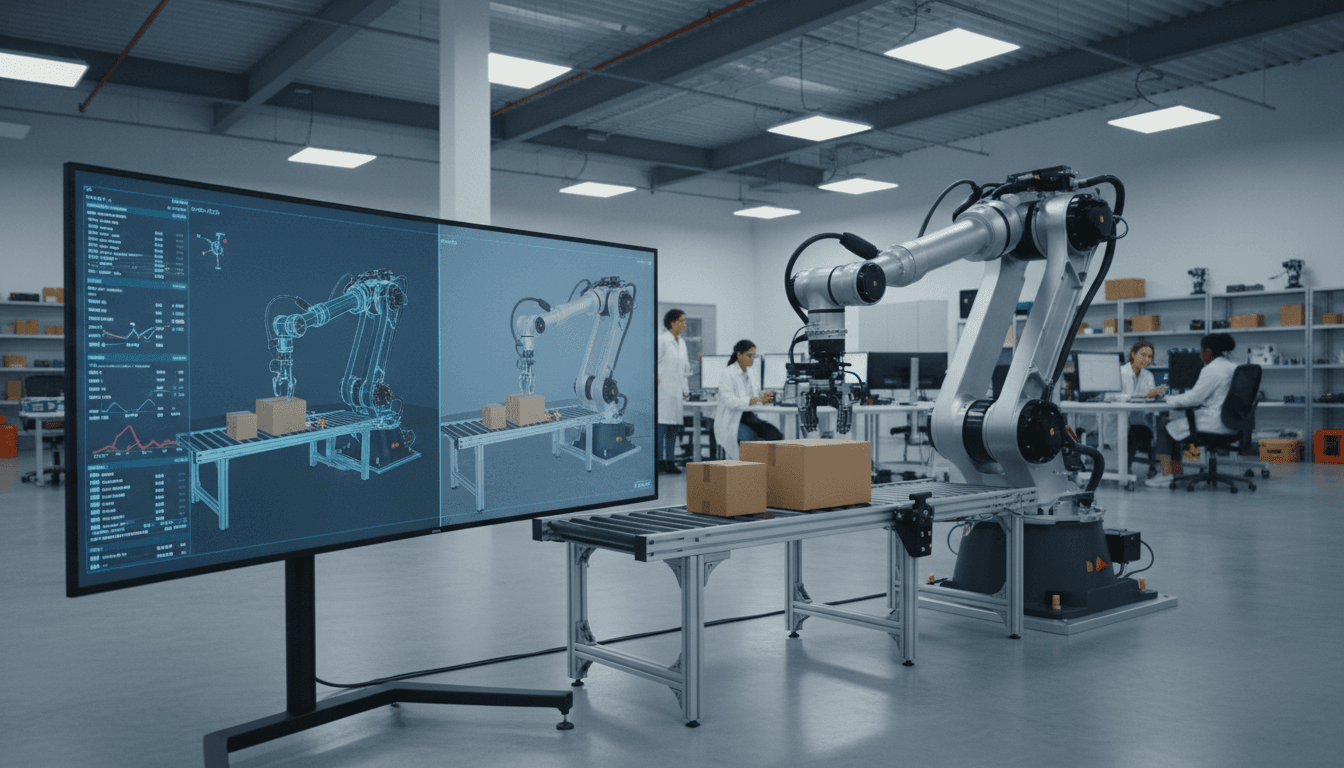

Simulation is where most robotics AI gets smart. Reality is where most robotics AI breaks.

That gap—often called sim-to-real—is one of the biggest reasons automation projects stall after a promising pilot. A robot can ace thousands of virtual warehouse picks or factory insertions and still fail on day one when lighting changes, friction is different, or a part is rotated three degrees.

The research idea behind generalizing from simulation is simple to say and hard to do: train in simulated worlds, then perform reliably in the messy real world. For U.S. companies building AI-powered digital services and automation—logistics, healthcare operations, manufacturing, retail fulfillment—this matters because simulation is how you scale learning without scaling risk.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and it takes a practical angle: what “generalizing from simulation” really means, why it’s becoming a foundation for American automation, and how to apply it when you’re shipping robots, not demos.

Generalizing from simulation: what it actually means

Generalizing from simulation means an AI policy trained in virtual environments keeps working when conditions change in the real world. Not just “it transfers once,” but it holds up across new lighting, camera angles, object textures, wear-and-tear, and human unpredictability.

In robotics, that usually means you train a control policy (or perception + control stack) using:

- A physics simulator (contacts, friction, collisions)

- Synthetic sensors (RGB, depth, force/torque)

- Procedurally generated scenes (objects, clutter, backgrounds)

- Reward functions (what “success” looks like)

The catch: simulators are always wrong. They approximate physics, don’t capture every micro-contact, and rarely match your camera noise, latency, or real actuator dynamics.

So when people say “generalize from simulation,” they’re really talking about building robustness to mismatch.

Why U.S. digital services should care

If you’re running digital services at scale—delivery networks, supply chain orchestration, hospital operations—automation is now part software and part physical execution. The software can be perfect; the physical world still fights you.

Simulation-based learning is attractive because it’s:

- Safer (no crashing forklifts)

- Faster (train 10,000 robots overnight—virtually)

- Cheaper (less lab time, fewer prototypes)

For U.S. startups in robotics and automation, simulation is often the only way to iterate quickly enough to compete.

Why robots fail in the real world (even after “great” simulation results)

Most sim-to-real failures come from unmodeled variability. Teams overfit to a narrow training distribution because the simulator “feels” broad while still being constrained.

Here are common failure modes I see in real deployments:

1) The physics mismatch problem

Contact dynamics are the classic offender:

- Grasping: small errors in friction or compliance change everything

- Insertion: pegs, connectors, and tight tolerances expose modeling gaps

- Locomotion: slip, uneven floors, worn wheels, debris

If the simulator assumes a coefficient of friction of 0.6 and your warehouse floor behaves like 0.4 on humid days, your learned policy can become brittle fast.

2) The sensor reality problem

Real sensors are ugly:

- Rolling shutter artifacts

- Motion blur

- Depth holes on reflective objects

- Calibration drift

- Latency and dropped frames

A perception model trained on clean synthetic images might look “accurate” on benchmarks and still mis-detect objects under fluorescent flicker.

3) The “operations” problem (humans, workflows, exceptions)

This is the part simulation rarely captures:

- Workers place items in nonstandard orientations

- Boxes arrive dented

- Labels peel

- People walk into the robot’s path

- The one SKU you didn’t model shows up during peak season

Generalization isn’t just a model property. It’s also an operational design property.

What actually helps AI generalize from simulation

Generalization improves when you train on variability on purpose, validate against reality early, and design policies that are robust—not clever.

Here are approaches that consistently matter for AI in robotics & automation.

Domain randomization (make simulation “too diverse”)

Domain randomization trains the model on wide variation so reality looks like “just another case.”

You intentionally randomize:

- Lighting direction, intensity, color temperature

- Camera pose, focal length, distortion

- Object textures, colors, wear patterns

- Mass, friction, restitution

- Sensor noise, latency, dropped frames

The stance I’ll take: if your simulator scenes look photo-real but not varied, you’re optimizing for the wrong thing. Diversity beats prettiness.

System identification (calibrate the sim to your robot)

System ID narrows the gap by fitting simulation parameters to match measured behavior.

Examples:

- Fit joint friction curves from motion tests

- Measure actuator delay and saturation

- Estimate payload mass distribution

This is less glamorous than training huge policies, but it’s one of the quickest ways to stop “mysterious” failures.

Hybrid training: simulation + targeted real data

Pure simulation is rarely enough for high-stakes tasks. A practical workflow is:

- Pre-train in simulation for breadth

- Collect a small amount of real data for the edge cases that matter

- Fine-tune and validate on real hardware

For many teams, the best ROI comes from real data that’s narrow but high-signal: the exact packaging material used in your fulfillment center, the real glare pattern on your conveyor line, the actual bin geometry, and the real camera mount that flexes when the robot accelerates.

Policy design that tolerates uncertainty

A policy that relies on perfect state estimates will fail. A policy that can recover from errors survives.

In practice that means:

- Closed-loop control (replan continuously)

- Recovery behaviors (regrasp, back off, retry)

- Conservative actions when confidence is low

- Using tactile/force feedback when vision is unreliable

A useful one-liner for stakeholders: “Robust robotics isn’t about never being wrong—it’s about failing gracefully and recovering fast.”

Where simulation generalization shows up in U.S. automation

Simulation-to-real generalization is already shaping how American companies scale automation in logistics, manufacturing, and healthcare. Here are concrete patterns.

Warehouse picking and packing

Robotic picking is a perfect sim-to-real test: varied objects, clutter, changing lighting, constant throughput pressure.

What works:

- Randomized clutter scenes in simulation

- Synthetic data pipelines for perception

- Real-world “hard examples” harvested from failure logs

The business payoff is straightforward: fewer manual touches per order and more consistent throughput during seasonal peaks.

Manufacturing: insertion, fastening, and inspection

Manufacturing tasks look repetitive until they aren’t. Tiny tolerances plus part variation create chaos.

Simulation helps teams train:

- Insertion with randomized tolerances

- Force-controlled assembly sequences

- Vision inspection under varying glare

If you’re deploying in U.S. plants, you also care about changeovers. Training policies that generalize reduces reprogramming time when suppliers, materials, or fixtures change.

Healthcare operations and service robotics

Hospitals are dynamic: carts move, hallways fill, signage changes, and “do not enter” zones appear.

Simulation-based learning supports:

- Navigation policies robust to crowd patterns

- Task planning under constraints

- Safety validation before limited real trials

For healthcare, generalization is tied directly to trust. If the robot behaves unpredictably once, staff will route around it—and your ROI evaporates.

A practical checklist for teams building sim-to-real automation

If your goal is a deployable system, treat simulation as a product, not a toy. Here’s a checklist you can use for robotics & automation projects.

1) Define “generalization” in business terms

Pick metrics that match operations:

- Success rate over new SKUs

- Mean recovery time after failure

- Throughput (items/hour) under peak variability

- Safety events per 1,000 operating hours

2) Build a “reality gap” test suite

Create a small set of real-world tests that you run weekly:

- Worst lighting corner

- Most reflective packaging

- Heaviest and lightest payloads

- Highest clutter density

- Most crowded hallway pattern

Treat it like regression testing for the physical world.

3) Log failures like a software team

Robotics teams that scale do three things consistently:

- Record sensor streams around failures

- Tag failure modes (slip, occlusion, misgrasp)

- Feed those examples back into training (sim and real)

If you can’t reproduce a failure, you can’t fix it.

4) Put guardrails around autonomy

Autonomy isn’t binary. In production, you want bounded autonomy:

- Confidence thresholds that trigger slow/stop

- Human-in-the-loop escalation paths

- Safe fallback behaviors

This is how you deploy earlier without creating unacceptable operational risk.

People also ask: quick answers about simulation generalization

Does simulation reduce the need for real-world data?

Yes—dramatically—but it doesn’t remove it. Simulation is best for breadth; real-world data is best for the weird, expensive corner cases.

What’s the fastest path to better sim-to-real performance?

Domain randomization plus a tight real-world validation loop. If you randomize widely and test on real hardware early, you stop overfitting to the simulator.

Is this only for robotics?

No. The same idea shows up in cybersecurity exercises, supply chain planning, and other digital services where you can run “what-if” worlds. Robotics just makes failures more visible.

Where this is heading for AI in robotics & automation

Generalizing from simulation is becoming the default way to scale physical AI, especially for U.S.-based teams trying to move fast without taking on outsized deployment risk. It’s also a competitive filter: companies that can turn simulated learning into reliable field performance ship more automation, with fewer surprises.

If you’re evaluating AI-powered automation for 2026 budgets—warehouse robotics, manufacturing cells, service robots—ask vendors and internal teams a blunt question: What’s your sim-to-real strategy, and how do you measure generalization on new conditions?

The next wave of U.S. digital services won’t stop at dashboards and workflows. It’ll include robots and automated systems that can handle real-world variability without constant babysitting. The teams that treat simulation as a serious engineering discipline will be the ones that deploy confidently.