Edible robot batteries are more than a stunt. See what RoboCake reveals about AI-driven robotics, safe materials, and automation that leaves no e-waste.

Edible Robot Batteries: A Strange but Serious Trend

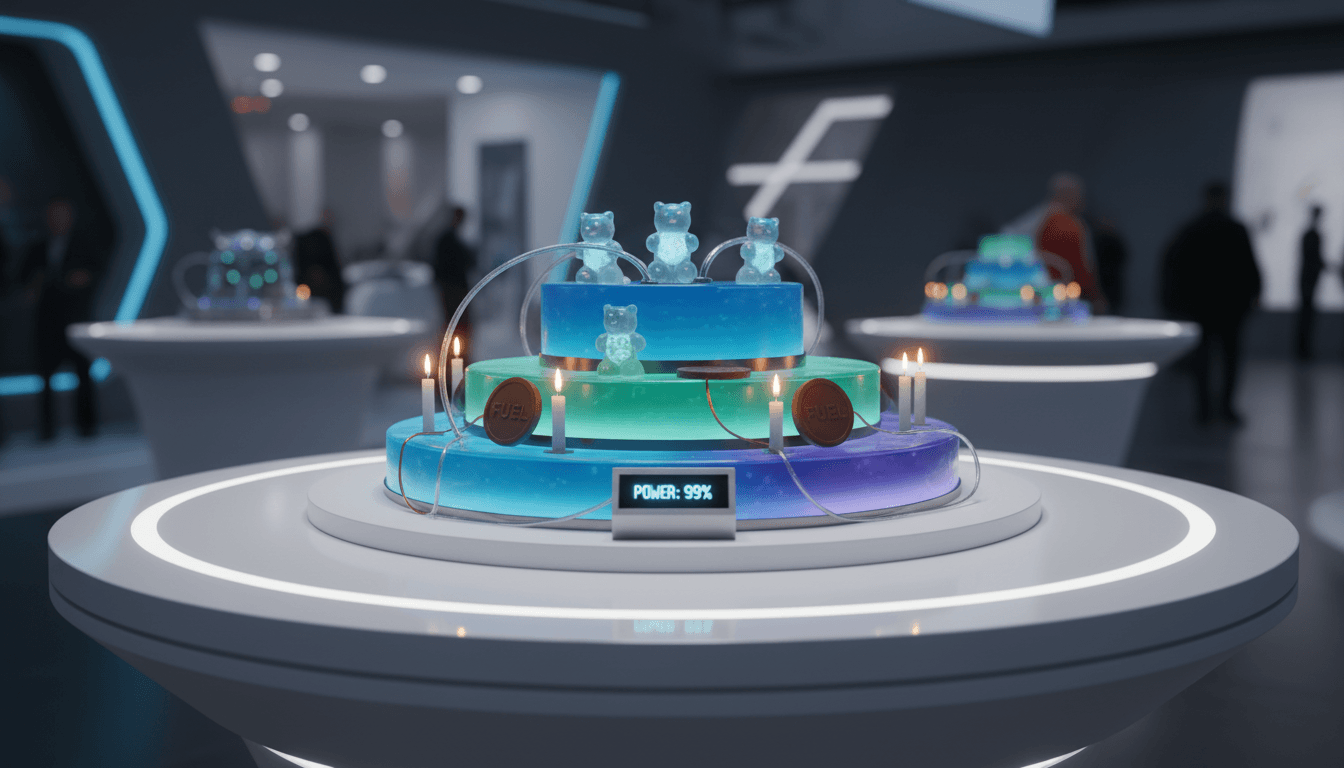

Expo demos are usually built to survive the week. The RoboCake—shown at Osaka Expo 2025—was built to be consumed.

On the surface, it’s a flashy piece of culinary theater: robotic gummy bears that wiggle and a set of rechargeable “batteries” that taste like dark chocolate with a tangy kick. But if you work in AI in robotics & automation, this dessert points at a serious engineering direction: robots designed for single-use, safe human contact, and zero e-waste recovery logistics.

Most companies get this wrong. They treat sustainability in automation as a packaging problem. RoboCake reframes it as a materials and lifecycle problem—and it’s a great case study for how AI can accelerate design in weird, non-traditional robotics environments.

RoboCake, explained: edible robots + edible rechargeable batteries

RoboCake is a collaboration between EPFL (Switzerland), the Italian Institute of Technology, chefs, and food scientists. The concept is simple to say and hard to execute: make moving robotic components that are safe to eat, and power them with a battery that’s also edible.

Here’s what the prototype includes:

- Edible robotic gummy bears made from gelatin, syrup, and colorants. They move using an internal pneumatic system that actuates limbs and head.

- Edible rechargeable batteries built from vitamin B2 (riboflavin), quercetin, activated carbon, and chocolate, used to power LED candles on the cake.

That isn’t a gimmick battery taped onto food. The project aim is broader: explore edible robotics as a platform for reducing electronic waste and food waste, and enable applications like ingestible sensing or novel delivery mechanisms.

From an automation lens, the headline isn’t “you can eat batteries.” It’s this:

Edible robotics are an engineering strategy for environments where retrieval, sterilization, and recycling are hard or impossible.

Why edible robotics matters to AI-driven automation

Edible robots sound like a novelty until you map them to real deployment constraints. In many automation scenarios, the hardest part isn’t motion planning or control—it’s what happens after the task.

The real pain: recovery and compliance

Consider any of these environments:

- Disaster zones where robots deliver supplies but retrieval is unsafe

- Clinical or assisted-care settings where devices must be non-toxic and low-choking-risk

- Food production lines where foreign-object contamination rules are strict

- Agriculture and livestock contexts where small devices can be ingested accidentally

If a robot can’t be reliably recovered, you have four bad options: leave it, retrieve it at high cost, overbuild it to reduce failure (expensive), or accept risk (usually unacceptable).

Edible (or fully biodegradable) robotics creates a fifth option: design for safe disappearance.

Where AI fits: designing the “material + motion + safety” stack

Edible robotics isn’t just “soft robotics with food.” It’s a constrained optimization problem:

- Must be food-safe (ingredients, byproducts, degradation)

- Must have predictable mechanical properties (elasticity, fatigue, fracture)

- Must support actuation and power (pneumatics, chemical energy, micro-power)

- Must maintain shelf stability (humidity, temperature, microbial control)

- Must satisfy regulatory and QA needs (traceability, allergen control)

This is exactly where AI helps in robotics and automation:

- Materials discovery and formulation optimization: ML models can search ingredient combinations for target mechanical and electrochemical properties.

- Simulation-driven design: differentiable simulators and surrogate models can speed iteration for soft structures and pneumatic channels.

- Generative design for soft actuators: AI can propose internal geometries that meet motion requirements while staying manufacturable in food-grade processes.

- Quality inspection automation: vision models can inspect edible components for cracks, voids, and contamination before assembly.

If you’re leading automation programs, the takeaway is practical: AI becomes more valuable as constraints multiply. Edible robots multiply constraints.

The edible battery is the real technical flex

Actuation gets the attention, but power is the bottleneck.

A battery—especially rechargeable—requires materials that can reversibly store and release energy. Traditional batteries rely on metals, solvents, and chemistries that are clearly not edible. RoboCake’s battery flips the materials palette:

- Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) and quercetin (a plant flavonoid) can participate in redox reactions.

- Activated carbon provides high surface area for charge storage.

- Chocolate isn’t just flavor—it’s also part of the structure and a familiar, trusted “carrier” material.

The batteries powered LED candles, which implies the system can deliver stable low-voltage output for a demonstrable task.

What this suggests for automation teams

Even if your company will never build edible batteries, this direction matters because it signals a broader shift:

- Power sources are becoming application-specific. In robotics, we’ve spent decades standardizing around lithium-ion. For disposable, ingestible, or contamination-sensitive devices, that assumption breaks.

- “Safe failure modes” are a product feature. If your robot ends up in the wrong place, the best outcome may be that it becomes harmless.

- Compliance-driven design is becoming a first-class constraint. Food safety, medical safety, and environmental safety can’t be bolted on.

The future of automation includes robots designed to be temporary—because permanence is expensive.

Beyond the cake: real use cases that aren’t science fiction

The RoboFood project’s public-facing demo is playful, but the application list is grounded. Here are the most credible directions, framed the way an automation buyer would think about them.

1) Emergency nutrition delivery in hard-to-reach areas

Direct answer: edible robotics can reduce recovery logistics in last-meter delivery.

A lightweight, biodegradable or edible device could deliver calories, electrolytes, or medicine in situations where retrieval is not feasible. The “robot” part matters when terrain, debris, or timing demands more than passive drops.

AI’s role would be route selection, basic autonomy, and robustness to changing conditions—while the physical device is designed to safely degrade or be consumed.

2) Medication delivery for dysphagia and assisted care

Direct answer: edible robotic components can turn medication into an easier-to-swallow experience.

For patients who struggle with pills, the barrier isn’t always the drug. It’s the format. Edible robotics could enable:

- timed release through edible encapsulation

- swallow-friendly shapes and textures

- sensory cues (taste changes) to confirm ingestion

This is an area where human-centered robotics meets formulation science. AI can help personalize size, texture, and release profiles based on patient needs.

3) Food freshness monitoring without “foreign objects”

Direct answer: edible sensors can reduce contamination risk in smart packaging and prepared foods.

Smart food monitoring often runs into a simple objection: “Don’t put electronics near my food.” Edible sensors—paired with edible power—change the conversation.

In practice, this could look like edible indicators embedded in prepared foods for supply chain validation, or ingestible markers used in controlled environments.

4) Novelty isn’t a dirty word in service automation

Direct answer: edible robotics can create premium experiences where entertainment drives margin.

In hospitality, theme parks, experiential retail, and events, novelty can justify high price points. The point isn’t to scale edible robots into factories. The point is to prototype new human-robot interaction models in emotionally positive contexts.

I’ve found that “playful robotics” often becomes a safe sandbox for technologies that later show up in serious settings—especially soft actuation, safe materials, and low-power design.

What it takes to commercialize edible robots (and what will block it)

Edible robotics will not scale because the demo is cool. It will scale only if teams solve a boring checklist.

Manufacturing reality: repeatability beats cleverness

Food-grade robotics has to deal with:

- batch-to-batch ingredient variability

- humidity and temperature sensitivity

- microbial growth risks

- shelf-life constraints

- sanitation and allergen segregation

For commercialization, the winning designs will be the ones that tolerate variability and still perform.

Safety and regulation: “edible” isn’t a single standard

If you’re thinking about edible components, you’ll need a clear internal definition:

- edible (safe to ingest)

- biodegradable (safe to leave behind)

- digestible (breaks down in the body)

- non-toxic on failure (safe if damaged)

Those are different requirements. Treating them as synonyms is a fast way to get stuck in validation.

Public perception: people hate eating “electronics”

The RoboCake team addressed this directly by making taste part of the design, not an afterthought. That’s smart.

Adoption will depend on trust signals:

- recognizable ingredients

- transparent labeling

- clear use-case justification (not “because we can”)

- reliable performance and predictable breakdown

Practical lessons for AI robotics leaders (even if you’ll never ship edible tech)

If you lead robotics & automation programs, RoboCake offers transferable lessons.

- Design the full lifecycle first. Retrieval, cleaning, disposal, and failure modes should be in the first product spec, not the last.

- Use AI where constraints are messy. The more you juggle material properties, safety limits, and performance targets, the more ML-based optimization pays off.

- Prototype in unconventional domains. Food is an extreme environment for safety, perception, and compliance. If your approach works there, it often generalizes.

- Treat “safe-to-touch” as a competitive advantage. Soft, non-toxic, low-energy robots will win in service, healthcare, and collaborative settings.

A better way to think about the RoboCake demo

The easy reaction is to laugh and move on. I think that’s a mistake.

RoboCake is a reminder that automation isn’t only about factories and warehouses. The next wave includes robots that are intimate—near our bodies, in our homes, and around our food. Those robots need different materials, different power systems, and different design philosophies.

If you’re building in the AI in Robotics & Automation space, this is the question worth sitting with:

When your robot’s job is done, do you want it to be durable—or do you want it to disappear safely?

If your team is exploring service robotics, food automation, or healthcare devices, it’s a good time to revisit your assumptions about materials, power, and lifecycle. That’s often where the next lead-generating product idea hides.