Dual-wheel balance robots like Tron 1 show how AI-driven mobility handles stairs, thresholds, and clutter—key for practical automation. Learn where they fit best.

Why Dual-Wheel Balance Robots Matter for Automation

A 20‑kg robot that can roll fast, hop low barriers, climb irregular stairs, and keep moving after someone shoves it isn’t just a fun demo. It’s a preview of where AI in robotics & automation is headed: machines that don’t need perfectly controlled floors, perfect lighting, or perfectly repeated setups to do useful work.

Most companies still talk about automation as if the environment will politely cooperate—flat concrete, taped lanes, and no surprises. Real facilities don’t work like that. Winter grit gets tracked into loading bays. Temporary ramps appear. Pallets drift a few centimeters out of position. And the most expensive downtime often comes from the “small stuff”: a threshold, a curb, a staircase, a cluttered corridor.

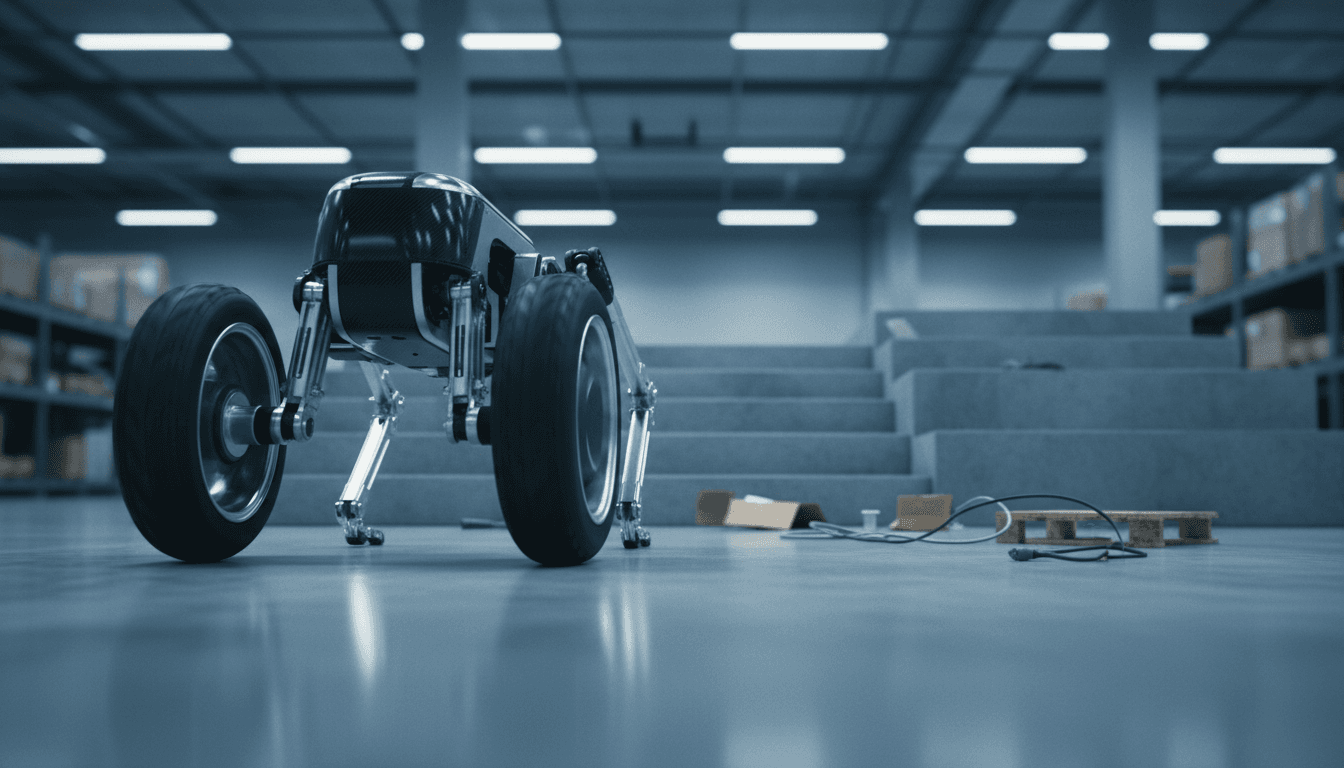

LimX Dynamics’ Tron 1 (a dual‑wheel, self‑balancing biped with modular foot ends) is interesting because it’s built around that messy reality. Its whole design says: mobility first, adaptability always. That’s exactly the direction service robots, logistics robots, and mobile manipulators need to take if you want deployments to scale beyond lab conditions.

Dual-wheel balancing is a practical bet (not a gimmick)

Answer first: Dual‑wheel balancing robots trade some raw terrain capability for speed, efficiency, and control, and AI makes that trade worthwhile.

Legged robots can step over obstacles, but they usually pay for that with energy use, mechanical complexity, and slower average speeds. Wheeled robots are efficient and fast, but they get humbled by stairs, thresholds, and clutter. Tron 1 is trying to sit in the middle: mostly wheel when you can, “leg it” when you must.

The core idea is simple: if the robot can dynamically balance (like a Segway), it can keep a narrow footprint, pivot quickly, and absorb disturbances. The hard part is making it stable while doing useful work—accelerating, braking, turning, rolling down steps, or getting bumped.

That’s where AI and modern control stacks earn their keep:

- State estimation fuses IMU data, wheel encoders, and (often) vision to maintain a reliable estimate of tilt, velocity, and contact.

- Disturbance rejection lets the robot recover from pushes without needing a rigid environment.

- Mode switching (wheel mode, “grip” mode, step-over behaviors) benefits from policies that can choose actions based on what’s ahead rather than a fixed script.

If you care about ROI, this matters because mobility failures don’t show up as small defects—they show up as missions that never finish.

What the Tron 1 demo is really showing

The headline clips—hurdles, irregular stairs, stepping over objects—look like athletic tricks. In operations, those movements translate to boring but profitable capabilities:

- Crossing door thresholds and elevator lips

- Handling temporary ramps and uneven transitions

- Surviving human interference in shared spaces

- Moving through construction-like clutter common in warehouses and hospitals

A robot that can’t handle these becomes a “pilot project robot.” It works during the tour and fails on Tuesday night.

Specs that signal where this fits in the market

Answer first: Tron 1’s published specs point to a research-to-early-deployment platform for autonomy, mobility behaviors, and embodied AI workflows.

From the source details:

- Size: 392 × 420 × 845 mm

- Weight: ~20 kg

- Actuators: 48‑V, peak torque 80 Nm

- Battery: 240 Wh, hot‑swappable, ~2 hours per pack

- Onboard compute: 12th‑gen Intel i3, 16 GB RAM, 512 GB storage

- Price: US$15,000 (with modular foot ends)

Here’s my take: that price and compute profile strongly suggest LimX is targeting teams that want a real robot they can program, test, and iterate on—without committing to six-figure humanoid platforms.

The hot‑swap battery detail is also not a “nice-to-have.” It’s a quiet acknowledgement that autonomy projects die by operational friction. If your robot requires a full shutdown to charge, your test cadence slows, your data collection suffers, and your team starts scheduling around a battery.

About those limitations (and why they’re still useful)

The listed constraints—~15° max climbing angle, ~15 cm obstacle height, -5 to 40 °C operating range—are not deal breakers. They’re a signal about where to deploy:

- Indoor logistics, facilities, and service environments

- Structured outdoor spaces (campus paths, loading zones) within temperature bounds

- Disaster-response research scenarios where you’re evaluating behaviors, not replacing human responders tomorrow

Also, published obstacle limits often describe conservative, repeatable performance. Demo videos can show higher one-off clears, but buyers should plan around specs, not highlight reels.

Where this kind of mobility wins: three real deployment patterns

Answer first: Dual‑wheel balancing robots make the most sense when you need fast indoor travel, occasional obstacle handling, and a platform that can grow into autonomy.

Below are three patterns I see repeatedly in successful robotics programs.

1) “Mobile sensor worker” for inspections and audits

Many organizations want frequent checks—thermal anomalies, leaks, door states, safety hazards, inventory presence—but they don’t want a person walking kilometers per shift.

A balancing wheel-biped is well suited because it can:

- Travel quickly across long corridors and aisles

- Handle transitions like ramps and steps

- Recover from minor bumps in busy environments

Add a sensor mast (RGB-D, thermal, gas detection) and you’ve got a platform for AI-driven inspection. The autonomy doesn’t need to be perfect on day one; even teleop with semi‑autonomous waypointing can deliver value.

2) “Last-30-meters” logistics where floors aren’t perfect

Warehouses already use AMRs, but the pain often starts beyond the warehouse: thresholds to office areas, elevator entrances, stair-adjacent routes, temporary stock rooms, and mixed-use hallways.

A robot that can roll efficiently yet step over clutter covers the “last-30-meters” gap:

- From receiving to staging areas with uneven transitions

- Between departments in hospitals or hotels

- Across older buildings where you can’t remodel every choke point

This connects directly to a bigger theme in our AI in Robotics & Automation series: automation expands when robots tolerate variation.

3) Education and R&D for embodied AI and control

Tron 1 ships in an education edition and looks designed for experimentation. That matters because embodied AI needs real-world iteration:

- Collecting data from disturbances and contact events

- Training policies for mode switching and recovery

- Testing perception under motion blur and vibrations

A moderately priced platform can outperform a “perfect simulator” because it forces your team to solve the hard parts: calibration, latency, safety constraints, and real sensor noise.

The AI layer: what actually makes agility usable

Answer first: Agility becomes valuable when AI turns it into repeatable behaviors, not stunts.

A demo can be remote-controlled or heavily scripted. A deployment needs reliability: the robot must decide when to roll, when to slow, when to step, and when to ask for help.

Here are the AI capabilities that separate “cool mobility” from “useful automation.”

Perception that understands traversability

Your robot doesn’t need to recognize 10,000 object classes. It needs to answer one question well: Can I drive over this, step over this, go around it, or stop?

That requires:

- Depth sensing or stereo vision to estimate obstacle geometry

- Terrain classification (slippery vs grippy, flat vs irregular)

- Confidence scoring so it knows when it’s unsure

Policy control for recovery and switching

Balancing platforms live and die by recovery. The Tron 1 footage showing self-righting under pushes is a big deal because shared spaces are chaotic.

In practical terms, your control policy needs to:

- Maintain stability during acceleration and turns

- Handle intermittent wheel slip

- Recover when one wheel hits an edge or debris

- Switch to “step” behaviors before getting stuck

Fleet operations and human-in-the-loop autonomy

Autonomy isn’t binary. The most successful deployments I’ve seen start with:

- Teleop for edge cases and mapping

- Semi‑autonomous waypoint navigation

- Autonomy with remote assistance (exceptions only)

Tron 1 supports remote control, semi‑automated tasks, and autonomous missions. The platform’s value rises dramatically if you pair it with a workflow that logs interventions and turns them into training data.

A practical rule: if you can’t measure why the robot needed help, you can’t reduce the help over time.

Buying checklist: when a balance bot is the right choice

Answer first: Choose a dual‑wheel balancing robot when you need speed + tight maneuvering and your environment has frequent small obstacles.

Use this quick checklist before you get excited by the demo video.

It’s a fit if…

- Your routes are mostly hard floors, with occasional thresholds/ramps/steps

- You care about quick repositioning (inspection rounds, delivery loops)

- Space is tight (corridors, elevators, crowded aisles)

- You can design tasks around a 15 cm obstacle planning assumption

It’s not a fit if…

- You need outdoor all-weather mobility beyond -5 to 40 °C

- Your site has steep grades beyond ~15°

- Your business case requires heavy payload handling without a stabilizing base

Questions to ask vendors (and your own team)

- What percentage of the task can be done in wheel mode?

- How does the robot behave on wet floors, mats, and cable covers?

- Can it use elevators reliably (doors, alignment, networking)?

- What’s the remote assist workflow when autonomy fails?

- How do we collect and label “failure moments” to improve the system?

What Tron 1 signals for 2026 automation programs

Dual‑wheel balance robots like Tron 1 are a reminder that the next wave of robotics winners won’t be decided by who posts the flashiest agility clip. They’ll be decided by who can ship robots that keep working when the environment is slightly wrong.

If you’re building an automation roadmap for 2026 budgets, this is the bet I’d make: invest in platforms and partners that treat mobility, recovery, and mode switching as first-class problems, because those are the blockers between pilot and production.

If you’re exploring how AI-driven robots can operate in your facility—logistics routes, inspection loops, or service workflows—what’s the most common “small obstacle” that breaks automation for you today: thresholds, stairs, clutter, or human traffic?