See what autonomous drone landings at 110 km/h mean for AI robotics. Learn the control, perception, and logistics use cases that drive real ROI.

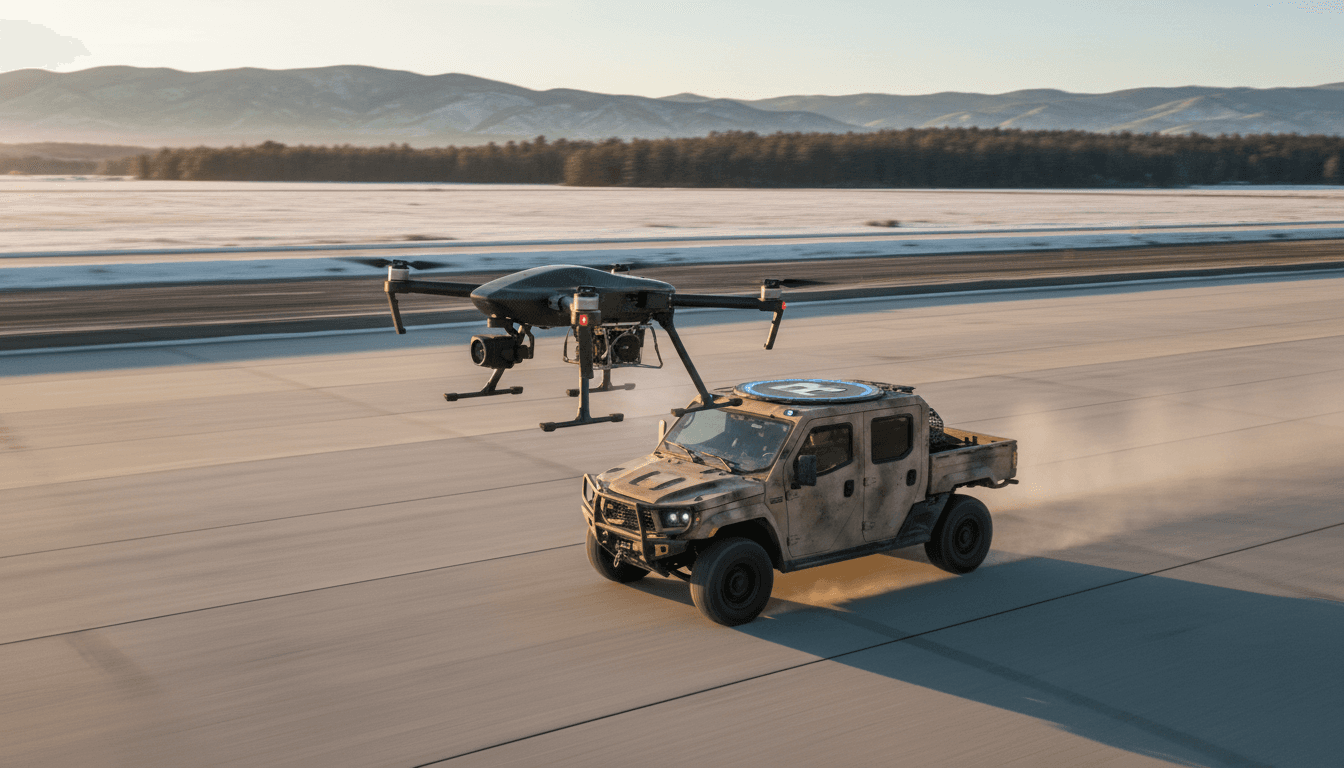

Autonomous Drone Landings on Moving Vehicles at 110 km/h

A drone landing on a moving vehicle at 110 km/h isn’t a party trick—it’s a stress test for real autonomy. At that speed, “close enough” becomes “missed the roof,” and any small error in timing, wind estimation, or motion tracking gets amplified into a failure.

This is why the video demo of a high-speed drone landing system matters for anyone building AI in robotics & automation programs. If your team is serious about automating inspection, inventory checks, perimeter monitoring, emergency response, or yard logistics, you don’t just need drones that fly. You need drones that can interact with the real world under motion—reliably, repeatedly, and safely.

The landing approach shown—combining lightweight shock absorption with reverse thrust—is a clean example of how modern robotics works when it’s done right: tight integration of mechanical design, control systems, and AI perception. And it points directly at what’s coming next in industrial automation: mobile docking, “infinite range” operations, and hands-off recharging without human intervention.

Why landing on a moving platform is the autonomy benchmark

Autonomous landing on a moving target forces a robot to solve multiple problems at once, in real time.

At a minimum, the system has to:

- Perceive the vehicle and the landing area (often under blur, glare, and vibration)

- Estimate relative motion (speed, direction, acceleration, and lateral drift)

- Plan a feasible approach path (respecting the drone’s dynamics)

- Control attitude and thrust precisely (including in wind gusts)

- Absorb contact without bouncing, tipping, or sliding off

That list reads like a robotics textbook because it is. And unlike many robotics demos, this one is brutally honest: when the target is moving fast, you don’t get to hide behind a controlled lab environment.

The hidden difficulty: timing errors explode with speed

The fastest way to understand the challenge is to translate “small mistakes” into distance.

At 110 km/h (~30.6 m/s):

- A 100 ms timing error becomes ~3 meters of miss distance.

- A 30 ms delay (very common in perception + compute + comms pipelines) is still ~0.9 meters.

So the autonomy stack has to be engineered for low latency and predictive control, not just “good accuracy on average.” In industrial robotics terms, this is the difference between a demo and a system you can insure.

What “expanding the landing envelope” really means

The source describes “drastically expanding the landing envelope” and being “more robust to wind, timing, and vehicle motion.” That phrase is doing a lot of work.

In practical robotics operations, landing envelope means:

- the range of speeds where landing is possible,

- the range of wind conditions tolerated,

- how much timing variance the system can withstand,

- how imperfect the touchdown can be before it becomes unsafe.

Most drone programs fail not because drones can’t fly, but because they can’t handle the messy edges:

- wind shear near buildings

- GPS multipath in yards and ports

- reflective roofs and low-contrast surfaces

- poor lighting at dawn/dusk (a real December problem)

- wet or icy surfaces

A landing system that deliberately blends mechanical compliance (shock absorbers) with active control (reverse thrust) is exactly how you make autonomy behave in those edges.

Why shock absorption matters more than people think

A lot of teams try to “solve landing” purely in software: better vision, better control loops, better SLAM.

That’s a mistake.

Physical contact is where perfect math meets imperfect reality. Shock absorption:

- reduces bounce and tip-over risk,

- protects motors/arms from impact loads,

- increases tolerance to slightly off-angle touchdowns,

- buys the controller time to stabilize after contact.

In other words, it converts a narrow, brittle landing condition into something you can operationalize.

Reverse thrust: active braking at touchdown

Reverse thrust isn’t just flair—it’s a way to reduce relative velocity at the moment of contact. If the drone can “grab” the air to decelerate quickly, it can sync with the vehicle’s velocity and reduce sliding.

In automation terms, this is the aerial equivalent of a robot arm using force control to seat a connector without damaging it.

Where this goes in manufacturing and logistics (the real ROI)

Autonomous drone landing on moving vehicles is a stepping stone to something operations teams actually want: drones that don’t need humans to reset, recover, recharge, or reposition them.

Here are three high-value applications that become realistic when moving-platform landing works.

1) Yard and port automation: drones that dock on trucks

If you run a distribution yard, you already have the moving platforms: yard trucks, trailers, and shuttles.

A “dock-on-vehicle” drone can:

- scan trailer IDs and seals while the truck is in motion,

- perform quick damage inspection on inbound loads,

- track inventory in open yards,

- follow a route without installing fixed charging stations everywhere.

Instead of building a drone base every 300 meters, the truck becomes the base.

2) Linear infrastructure inspection without stopping traffic

Think highways, pipelines, rail, and power corridors.

A drone that can land on a moving vehicle enables:

- mobile inspection convoys,

- rapid battery swaps on the move,

- fewer roadside stops (a safety and cost win).

This matters in winter months: shorter daylight windows and harsher weather increase the operational value of “keep moving” workflows.

3) Emergency response: fast deployment with safe recovery

For incident response teams, recovery is often the bottleneck. A drone that can land back on a moving command vehicle reduces:

- time spent retrieving the drone,

- exposure to hazards,

- the need for a dedicated pilot at each site.

Autonomy earns its keep when it reduces headcount and risk at the same time.

The autonomy stack behind high-speed docking

Autonomous landing looks simple when it works. Under the hood, it’s a stack where failure can come from anywhere.

Here’s the system breakdown I’ve found most useful when assessing vendors or internal prototypes.

Perception: you need a “good enough” world model at high frame rates

For moving-platform landing, perception is usually a fusion of:

- downward/forward cameras

- IMU

- barometer

- optionally RTK GPS (but don’t rely on it near structures)

- optionally lidar/radar depending on cost and weight

The hard part isn’t recognizing a vehicle. It’s tracking a specific landing zone with enough temporal consistency to support closed-loop control.

Estimation: relative motion is the truth that matters

Autonomy succeeds or fails on relative position and velocity. Absolute accuracy is nice, but docking is fundamentally a relative navigation problem.

That’s why robust systems:

- model latency explicitly,

- predict future target pose (not just current pose),

- degrade gracefully when confidence drops.

Control: precision without brittleness

A control system for docking needs to be aggressive enough to converge quickly, but conservative enough to remain stable under wind and turbulence.

If you’re evaluating a solution, ask how it handles:

- gust rejection

- lateral drift close to touchdown

- “go-around” behavior when alignment is off

- contact stabilization after first touch

A safe go-around is not optional. It’s the difference between a system you can scale and one you only demo.

A practical checklist for teams considering drone docking

If you’re exploring drones for automation—especially in logistics—use this checklist to keep the conversation grounded.

Operational questions (the ones that decide ROI)

- What is the recover-and-relaunch cycle time today? Minutes matter.

- How many human touches per flight hour? Your goal should be trending toward zero.

- Where do failures cluster? Wind? Low light? Dirty sensors? Vehicle vibration?

- What’s your “no-fly/no-land” policy? Define it before you scale.

Technical questions (the ones that decide reliability)

- What sensors are required, and what happens if one degrades?

- How does the system detect and handle latency?

- Does it require markers on the vehicle, or can it dock markerless?

- What’s the landing tolerance (offset, angle, speed) before it aborts?

- How is contact handled mechanically (compliance, friction, retention)?

Integration questions (the ones that decide timeline)

- Can docking events trigger workflows in your WMS/TMS?

- Can the drone share mission context with other robots (ground vehicles, robotic arms)?

- How do you handle audit logs for safety and compliance?

If a vendor can’t answer these cleanly, they’re selling a demo.

The bigger trend: robots that “talk” to other robots (and to AI)

One of the most telling signals in the broader robotics ecosystem right now is the push toward tooling that lets AI systems interface with robot stacks—particularly with ROS-based fleets.

When drones can dock on moving assets and also connect to higher-level orchestration (task planning, natural-language interfaces, multi-robot coordination), you get a new operating model:

- fewer specialized operators,

- faster mission changes,

- tighter coupling to business systems.

That’s where this series—AI in Robotics & Automation—is heading: not “cool robots,” but operational autonomy that reduces friction in real workflows.

What to do next if you’re building AI-driven drone automation

High-speed landing on a moving vehicle is a clear signal that autonomy is maturing past waypoint navigation into interactive robotics—systems that coordinate with other moving machines.

If you’re responsible for robotics strategy in manufacturing, logistics, or field service, the next step isn’t to ask whether this is possible. It is. The next step is to decide where docking autonomy removes enough operational pain to justify deployment.

Start small: choose one route, one yard, or one inspection loop where recovery time and human touches are measurable. Then evaluate solutions based on their ability to handle wind, latency, and go-arounds—not just their highlight reel.

A question worth sitting with: If your drones could dock reliably without stopping vehicles, which part of your operation would change first—and how much labor would you get back?