Asymmetric actor-critic speeds up image-based robot learning by training with privileged state while deploying from pixels. See how it supports US automation.

Asymmetric Actor-Critic: Smarter Robots From Images

Most teams trying to train robots from camera input hit the same wall: the robot can’t learn fast enough from pixels alone. Simulation helps, but the real world is messy. Sensors drift. Lighting changes. A gripper slips by two millimeters and the policy falls apart.

That’s why asymmetric actor-critic methods matter for image-based robot learning. The core idea is straightforward: during training, let the “critic” (the part judging how good an action is) see more information than the “actor” (the part that actually drives the robot). At deployment, the robot still runs on images, but it got there with a tutor that had a clearer view.

In this installment of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, I’ll break down what asymmetric actor-critic means in practice, why it’s become a practical pattern in reinforcement learning for robotics, and how it connects to real US digital service ecosystems—logistics, manufacturing, and even customer-facing automation.

Asymmetric actor-critic, explained in plain terms

Asymmetric actor-critic is a reinforcement learning setup where the policy uses limited observations (like camera images), but the value function uses privileged training information (like exact object poses or full simulator state).

In actor-critic reinforcement learning:

- The actor learns a policy: “given what I observe, what action should I take?”

- The critic learns a value estimate: “how good is that action likely to be?”

In robotics, the actor often needs to operate with realistic constraints—typically RGB images, maybe depth, and joint states. But during training (especially in simulation or instrumented lab setups), you may have access to extra truth:

- ground-truth object position and orientation

- exact robot state without sensor noise

- contact events and forces

- segmentation masks

- full environment state from a simulator

Asymmetry means: the actor doesn’t get to “cheat,” but the critic can. That makes training far more stable because the critic’s job—estimating value—is statistically easier when it has better state information.

Why the “critic gets more” trick works

The critic’s estimate is a learning signal. If that signal is noisy, the actor learns slowly or learns the wrong thing.

Pixels create noise in two ways:

- High-dimensional input: Images carry a lot of irrelevant variation (shadows, reflections, background clutter).

- Partial observability: A single camera view may hide key state information (occlusions, depth ambiguity).

Giving the critic privileged information improves the quality of the training signal, which often translates to:

- better sample efficiency (fewer rollouts needed)

- more stable training curves

- policies that can learn complex manipulation faster

The reality? You’re not “making the robot smarter at deployment.” You’re making training less blind.

Why image-based robot learning is still hard (and what asymmetry fixes)

Training directly from images is hard because the learning algorithm must solve perception and control at the same time.

If you’ve ever watched a policy fail because the camera exposure changed, you’ve seen the problem: pixels are brittle unless you actively design for robustness.

Asymmetric actor-critic helps by separating concerns:

- The actor learns the real task: act from images.

- The critic learns to judge actions with a “clean” state representation.

This is particularly useful in a common robotics workflow:

Sim-to-real training pipelines

Most practical teams do some version of:

- Train in simulation (cheap, parallel, instrumented)

- Transfer to real robots (expensive, safety constraints)

Simulation gives you privileged state “for free.” That makes it a natural fit for asymmetric training.

But you still need the actor to survive reality. So the actor is trained on images (plus whatever proprioception you’ll have in production), while the critic uses full simulator state to keep the learning signal sharp.

Instrumented real-world training

Even in real labs, you can temporarily add sensors during training:

- motion capture

- AprilTags / fiducials

- force-torque sensors

- calibrated depth cameras

Those sensors are often too expensive or too finicky for deployment at scale, but they’re great teacher signals for the critic.

A practical rule: if you can measure it in the lab but can’t afford it in production, it’s a good candidate for “critic-only” information.

What this means for US automation and digital services

Robots that learn from images are finally becoming “software-shaped” components in larger digital service ecosystems. That matters in the United States right now because automation is being pulled by two pressures at once: labor constraints in physical operations and higher customer expectations in digital experiences.

Asymmetric actor-critic doesn’t just advance robotics research; it supports a broader trend: turning physical work into an AI-driven service layer.

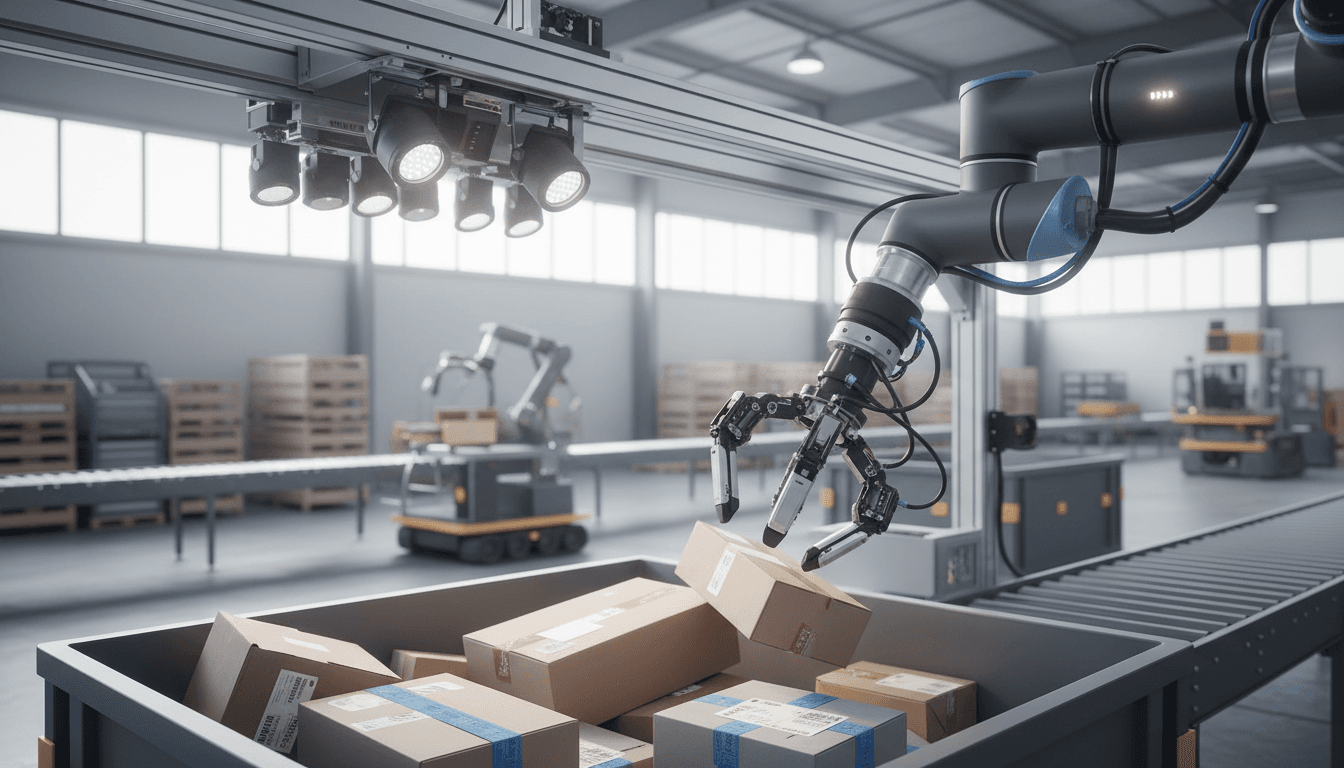

Logistics: vision-first picking, packing, and sortation

Warehouses already run on digital systems—WMS, inventory forecasting, routing, order promises. The physical bottleneck is often “the last meter” inside the building:

- bin picking

- parcel singulation

- exception handling (damaged labels, odd shapes)

Vision-based robot learning is appealing because it reduces rigid fixturing and hard-coded rules. Asymmetric training speeds up getting a policy that can handle visual variability, which is the entire warehouse reality in December and January: seasonal packaging, returns, peak throughput, and constantly changing SKU mixes.

A realistic integration pattern looks like this:

- Robot policy handles pick/place from camera images

- Digital service layer manages task allocation, audit trails, and exception queues

- Human-in-the-loop UI resolves ambiguous cases, producing new training data

That’s not “robots replacing software.” It’s robots becoming another endpoint in a digital workflow.

Manufacturing: faster changeovers, fewer brittle vision scripts

Traditional industrial vision pipelines rely on:

- fixed lighting

- tuned thresholds

- hand-designed features

It works until a supplier changes surface finish, a camera gets nudged, or the line adds a product variant.

Image-based reinforcement learning (with asymmetric critics during training) is one route to reduce the cost of changeovers, because policies can learn invariances that rule-based systems don’t.

If you’re building a US manufacturing automation roadmap, this matters because many plants are asked to run high-mix, low-volume production. The economics favor systems that adapt without weeks of reprogramming.

Customer service automation: the bridge people miss

Here’s the parallel that’s easy to overlook: asymmetric learning shows up in digital services too.

In customer communication automation (chat, email triage, outbound marketing), the “actor” is the model generating a response or decision based on limited context (what’s in the ticket, the customer message, the product).

But during training you can give the “critic” richer supervision signals:

- downstream outcomes (refund avoided, churn reduced)

- human QA scores

- policy compliance flags

- long-term customer satisfaction metrics

Same pattern, different domain: the production model runs with constraints, but the evaluator learns with more complete outcome data.

How to apply asymmetric training in real projects

If you want asymmetric actor-critic to pay off, treat it as a product strategy, not a neat paper trick. The method is only as good as the privileged information you can reliably supply during training.

Step 1: Define “deployment observations” first

Write down exactly what the robot will have at runtime:

- RGB? Depth? Both?

- Camera placement and field of view

- Proprioception: joint angles, velocities, gripper state

- Latency constraints (control frequency)

If you don’t lock this down, you’ll accidentally train policies that depend on signals you can’t ship.

Step 2: Identify privileged signals that are cheap in training

Good candidates are signals that are:

- available in simulation

- measurable in the lab

- too expensive or unreliable in production

Examples:

- object pose from simulator state

- segmentation masks from rendering engine

- contact flags from physics engine

- motion capture markers during training only

Step 3: Engineer the critic input carefully

A common failure mode is to “stuff everything into the critic” without thinking about distribution shifts.

What works better:

- keep privileged features clean and low-dimensional (poses, relative transforms)

- normalize consistently

- avoid privileged signals that disappear in real-world fine-tuning unless you’ll keep training with them

Step 4: Plan for fine-tuning on real data

Even great sim training benefits from real-world adaptation. The good news: asymmetric setups can still help.

A practical approach is:

- pretrain policy in sim with asymmetric critic

- collect real rollouts with safety constraints

- fine-tune using a mix of image augmentation + limited privileged instrumentation

- gradually remove privileged sensors from the training loop

This staged approach is often the difference between a demo and something that runs on a schedule.

Step 5: Measure the right metrics

Teams often track only success rate. That’s not enough.

Track:

- time-to-success (cycle time)

- intervention rate (how often a human fixes it)

- recovery behavior (what happens after a slip)

- generalization across lighting, backgrounds, and object variants

- cost-per-pick or cost-per-task in real ops

If your goal is leads (and real deployments), these operational metrics are what decision-makers care about.

Common questions people ask about asymmetric actor-critic

Does the actor “learn to rely” on privileged information?

No—not if you keep privileged information out of the actor input. The actor can’t use what it never sees. The risk is indirect: if your critic learns value estimates that don’t correlate with what the actor can observe, learning can become unstable. That’s a design problem, not a deal-breaker.

Is this only useful in simulation?

Simulation is the easiest place to do it, but it’s not the only place. Many robotics teams use temporary instrumentation in the lab to provide critic signals during training, then ship a simpler sensor stack.

What tasks benefit most?

Tasks with messy vision and contact-rich dynamics tend to benefit:

- bin picking and decluttering

- insertion and assembly (peg-in-hole variants)

- grasping with deformable objects (bags, soft packaging)

If the task is basically deterministic and fully observable, you may not need the complexity.

Where this fits in the “AI in Robotics & Automation” story

Asymmetric actor-critic for image-based robot learning is one of those ideas that sounds academic until you try to ship a robot. Then it feels obvious: give training every advantage you can, but don’t cheat at runtime.

And that’s the bigger theme of this series: modern automation in the US is increasingly a blend of physical systems and digital services. The winners aren’t the teams with the fanciest demo—they’re the ones who can train reliably, monitor in production, handle exceptions, and keep improving.

If you’re evaluating AI-powered robotics for logistics, manufacturing, or service operations, the question to ask is practical: what privileged signals can you capture during training to make image-based policies learn faster—and what does your digital service layer look like once the robot is live?