Artificial tendons made from hydrogel let muscle-powered robot grippers move 3× faster with 30× more force. Here’s what it means for AI robotics and automation.

Artificial Tendons for Stronger AI Robot Grippers

A muscle-powered robot gripper that’s 3× faster and delivers 30× more force isn’t a minor lab tweak—it’s a reminder that robotics progress often comes from the unglamorous parts: the connectors, the interfaces, the “boring” mechanical details that decide whether your actuator’s power actually reaches the end effector.

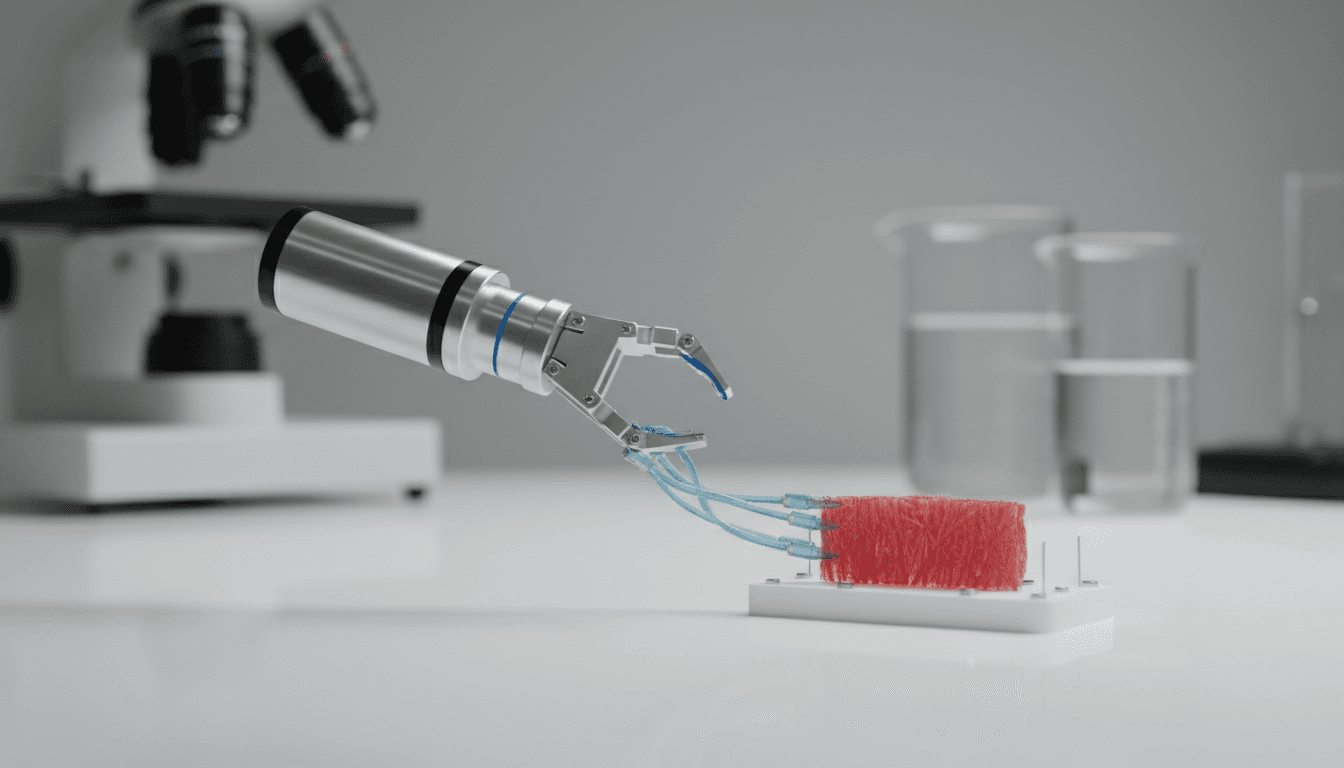

MIT researchers recently showed that adding tough, flexible hydrogel “artificial tendons” between lab-grown muscle and a robotic gripper dramatically improves speed, force, and durability (the system ran for 7,000 contraction cycles). For anyone building AI-driven robotics for automation—especially grippers, micro-manipulators, and adaptive tools—this is a big deal because it tackles a persistent failure point: force transmission across mismatched materials.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and I’m going to take a clear stance: biohybrid robotics won’t matter for industry until it becomes modular, controllable, and testable like any other actuator stack. Artificial tendons are a concrete step in that direction.

Why biohybrid robots have been underpowered (until now)

Biohybrid robotics uses living muscle tissue as an actuator paired with a synthetic “skeleton.” The pitch is compelling: muscle scales down well, can self-repair to a degree, and can adapt with training. The reality has been harsher—many prototypes look impressive on video but struggle to deliver meaningful work.

Here’s the core problem: directly attaching soft muscle to rigid robot structures wastes muscle and wastes force.

When muscle is looped around posts or glued onto a rigid frame, you get three practical issues:

- You sacrifice active tissue just to create attachment points. That attachment tissue doesn’t contribute much to motion.

- You create a mechanical mismatch. Soft muscle meets stiff plastic/metal. Under load, the muscle can tear or detach.

- Only a fraction of the contraction produces useful motion. The center contracts, the ends deform, and the structure doesn’t move much.

If you work in industrial automation, this should sound familiar. It’s the biological version of “my motor is fine, but the coupling/backlash/compliance kills precision.”

Artificial tendons address the coupling problem. They sit between muscle and skeleton with intermediate stiffness—closer to how bodies solve it.

What MIT’s artificial tendons actually change

The MIT team built a muscle–tendon unit: a small piece of lab-grown muscle with hydrogel tendons attached on both ends, then wrapped those tendons around posts on a robotic gripper.

The headline numbers are worth repeating because they’re unusually concrete for biohybrid work:

- 3× faster pinch motion

- 30× greater force

- 7,000 cycles of repeated contractions while maintaining performance

- 11× improvement in power-to-weight ratio (meaning less muscle for the same work)

Those gains didn’t come from “stronger muscle.” They came from better transmission.

The tendon is the product, not the accessory

Most teams treat muscle as the star and the attachment method as an afterthought. This work flips that mindset.

A tendon is not just a strap. It’s a mechanical impedance matching layer:

- Too soft, and it stretches without pulling the skeleton.

- Too stiff, and it concentrates stress and rips the muscle interface.

- Correctly tuned, and it transfers contraction into controlled motion.

MIT modeled the system as three spring elements (muscle, tendons, skeleton) and used known stiffness values for muscle and the gripper structure to calculate the tendon stiffness needed for the target motion. That’s a practical engineering move: spec the interface, don’t guess it.

Why hydrogels make sense here

Hydrogels are squishy, tough polymers that can be engineered to:

- stretch repeatedly without snapping,

- adhere to biological tissue and synthetic structures,

- maintain properties in wet environments.

That last point matters because biohybrid robots live in hydrated conditions. A tendon material that performs well dry but degrades or delaminates in wet conditions is dead on arrival.

Where AI fits: control, optimization, and reliability

A fair criticism of biohybrid robotics is that it’s hard to control compared to electric motors or pneumatic cylinders. I agree—without AI and good sensing, biohybrid actuation stays a lab curiosity.

Artificial tendons make AI control more plausible because they increase repeatability and reduce failure at the attachment interface. Then AI can do what it’s good at: handle variability, adapt control policies, and optimize performance under changing loads.

AI control loop benefits from a better mechanical interface

When the coupling is unstable (muscle tearing, slipping, unpredictable compliance), your control system becomes a mess. You can’t model it well, and you can’t learn it reliably.

A tuned tendon layer gives you:

- more consistent force-to-motion mapping (less “mystery compliance”),

- higher signal-to-noise in sensor readings (strain, position, force),

- fewer catastrophic failures that corrupt training data and ruin uptime.

Practical AI use cases for muscle–tendon robotics

If you’re thinking about AI-powered automation, here are concrete ways AI could pair with tendon-enabled biohybrid actuators:

-

Adaptive gripping for fragile items

- Use tactile/force feedback + learned policies to modulate stimulation patterns.

- Target: food handling, lab automation, electronics assembly.

-

Self-tuning actuation (“digital tendons”)

- Use reinforcement learning or Bayesian optimization to pick stimulation waveforms that maximize force while minimizing fatigue.

- Target: micro-grippers, precision pick-and-place.

-

Predictive maintenance for living actuators

- Track cycle count, contraction amplitude, response time, and tendon strain.

- Predict when performance is drifting before it fails.

-

Morphology-aware planning

- AI planners that understand compliant, muscle-like actuation can choose grasps and motions that avoid overload.

The big idea: as the hardware becomes more modular and repeatable, AI becomes more useful—and easier to validate.

What this could mean for automation in 2026 and beyond

December 2025 is an interesting moment for robotics. Budgets are tightening in some sectors, but expectations for automation keep rising—especially for warehouse throughput, lab productivity, and healthcare assistance. Companies want robots that are safer around people and more capable with irregular objects.

Biohybrid actuators won’t replace motors on factory arms next year. But tendon-enabled muscle units could open new categories where today’s actuators struggle.

Logistics and manufacturing: the gripper problem is still unsolved

Most companies get this wrong: they obsess over the robot arm and treat the gripper as a commodity. Yet in real operations, failures come from grasping variability—packaging differences, deformable items, odd geometries, and the cost of excessive force.

A muscle–tendon gripper architecture could matter because it naturally supports:

- compliance (less damage to items),

- high force for its weight (better at small scales),

- potentially quieter, smoother motion (useful in human-shared spaces).

Pair that with vision + tactile AI, and you get a gripper that doesn’t just “close.” It closes with intent.

Surgical and micro-manipulation: tiny scale is where muscle wins

Ritu Raman’s point is one many robotics teams learn the hard way: making traditional actuators small is painful. At micro scales, friction, manufacturing tolerances, and packaging kill you.

Muscle is inherently cellular and distributed; it scales down naturally. Tendons make it connectable.

That combo is especially relevant for:

- micro-surgical tools,

- catheter-like manipulators,

- lab-on-a-chip handling,

- minimally invasive sampling tools.

AI’s role here is straightforward: precision control under uncertainty, plus safety constraints.

Field and exploratory robots: durability and “self-healing” as a strategy

One reason biohybrid robotics attracts defense and research funding is the vision of robots that can tolerate damage and keep going.

Artificial tendons help because the interface is a frequent failure point. If you can reduce tearing and detachment—and eventually add protective “skin” casings as the MIT team suggests—you inch closer to robots that operate outside pristine lab environments.

I’m still skeptical about near-term deployment in harsh outdoor settings. But for semi-controlled environments (labs, cleanrooms, hospitals), the path is clearer.

Implementation lessons for robotics teams (even if you don’t use muscle)

You might read this and think: “Cool science, not relevant to my electric gripper.” I’d argue it’s relevant because the tendon concept maps directly to modern automation.

1) Treat interfaces as first-class design parameters

The best actuator in the world is useless with a bad interface.

- Model stiffness and compliance explicitly.

- Design for fatigue life and cycle testing early.

- Assume your first attachment method will fail under realistic loads.

2) Build modular actuation units you can swap

MIT frames tendons as interchangeable connectors. That’s the right direction.

In industrial AI robotics, modularity enables:

- faster iteration,

- easier A/B testing,

- cleaner data collection (same skeleton, different actuator unit),

- lower downtime.

3) Close the loop with sensing from day one

Force and position feedback aren’t “nice to have” once compliance enters the system. If you’re exploring soft or biohybrid actuation, plan for:

- tendon strain measurement,

- fingertip force sensing,

- cycle-to-cycle performance tracking.

AI control without good signals becomes guesswork.

The real milestone: modular, testable biohybrid actuation

Artificial tendons don’t magically solve biohybrid robotics. Muscle culture, longevity, packaging, hydration, contamination control, and regulatory pathways are all hard. But this tendon work hits a key point: it turns muscle actuation into something closer to an engineering component rather than a fragile art project.

For the AI in Robotics & Automation world, that’s the direction that matters. AI thrives on systems that are repeatable enough to learn, but flexible enough to adapt. Artificial tendons make muscle-powered robots more repeatable—while keeping their natural compliance.

If you’re evaluating next-generation robotic automation, the question to ask isn’t “Will we replace motors with muscle?” It’s: Where would a compliant, high power-to-weight actuator—paired with AI control—solve a problem my current hardware can’t?