Learn what deep-sea ROV missions teach about AI robotics: edge autonomy, bandwidth limits, reliability, and human-in-the-loop operations that scale.

AI Underwater Robots: What Real Missions Teach Teams

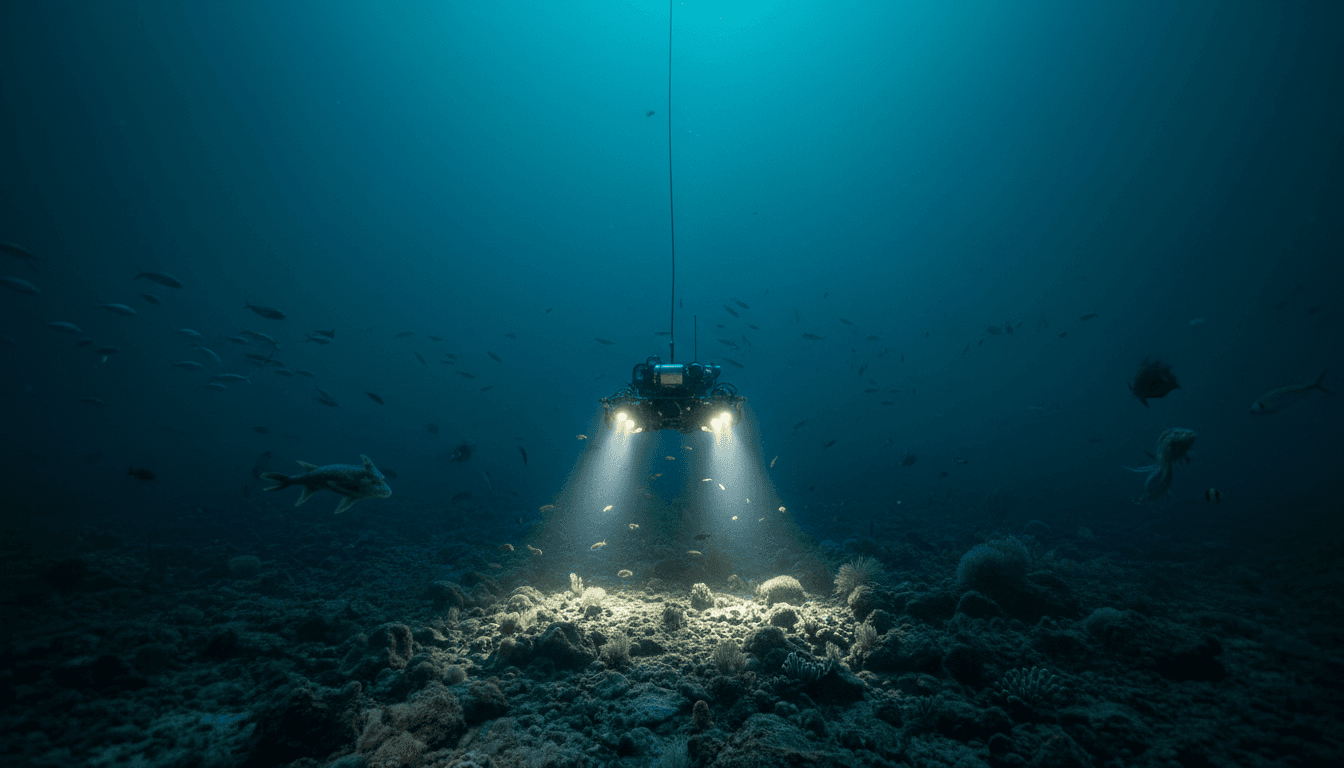

A deep-ocean ROV can be connected to the surface by kilometers of cable with only a few optical fibers, yet it’s expected to deliver crisp video, sensor data, and precise control—while operating in darkness under crushing pressure. That constraint alone explains why underwater robotics has become a proving ground for practical AI: when bandwidth is tight and the environment is hostile, robots have to think locally.

Levi Unema’s career path—going from factory automation to building, maintaining, and piloting deep-sea ROVs for scientific expeditions—highlights a reality many engineering teams don’t fully appreciate until they’re deployed: the hardest part isn’t “making the robot move.” It’s keeping the robot useful when everything around it tries to break it.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and I’m going to take a stance: underwater robotics is one of the best places to learn what “production-grade AI robotics” actually means. Not demos. Not lab benchmarks. Real missions.

Underwater robotics forces AI to earn its keep

Key point: Deep-sea robots make AI practical because communications, power, and maintenance are constrained—so autonomy and onboard intelligence aren’t optional.

In many industrial settings (factories, warehouses), you can often “brute force” reliability with infrastructure: stable Wi‑Fi, redundant compute, quick access to spare parts, and a technician a short walk away. In the deep ocean, you get none of that. You get:

- Extreme pressure that dictates mechanical layout (small pressure housings, tight packaging, careful isolation)

- Limited comms (high-value optical fibers shared across video + instruments)

- Long mission times with no easy reset button

- Field repairs with whatever is on the ship

That combination pushes robotics teams toward AI patterns that also translate cleanly into industrial automation:

Where AI helps first: onboard triage and prioritization

When “all data can’t go up the cable,” robots need to decide what matters.

In ocean exploration, this can mean:

- Event detection: flagging rare biological activity, unusual geology, or instrument anomalies

- Smart compression: prioritizing frames/regions of interest rather than streaming everything at full fidelity

- Quality scoring: assessing whether a sample or image is usable before you waste time collecting more

In industrial automation, the equivalent is edge AI that decides whether to:

- stop a line,

- reroute a part,

- call a human,

- or keep running and log evidence.

The lesson: AI isn’t there to “make it autonomous.” It’s there to manage scarcity—bandwidth, time, attention, and energy.

A note on autonomy: ROVs today, AUVs tomorrow

Unema’s work focuses on ROVs (remotely operated vehicles), where a pilot drives the robot and a science team directs priorities from the live feed. That human-in-the-loop model is powerful—and it’s also a template for how many companies should deploy AI robotics.

A practical roadmap looks like this:

- Assistive autonomy (AI helps operators: stabilization, collision avoidance, auto-heading, station-keeping)

- Task autonomy (AI performs bounded tasks: scan this transect, keep altitude, follow a pipeline)

- Mission autonomy (AI plans and adapts: explore a region, optimize sampling, handle contingencies)

Most teams should stop pretending they’re jumping from (1) to (3). The winning approach is progressive automation with tight feedback loops.

Engineering constraints underwater map directly to industrial robotics

Key point: The same trade-offs Unema describes—size, weight, reliability, maintainability—are the trade-offs that decide whether AI robotics succeeds in warehouses and factories.

Unema describes the constant pressure to keep electronics small (titanium housings are expensive; mass requires buoyancy; buoyancy changes vehicle dynamics). Underwater, that’s physics. In industrial robotics, it shows up as:

- space constraints inside end-effectors, mobile robots, and inspection heads

- thermal envelopes (especially in sealed enclosures)

- compute placement decisions (edge vs. on-prem vs. cloud)

Here are three “deep sea” lessons that transfer surprisingly well.

1) Treat packaging as an AI requirement, not a mechanical detail

If your AI stack assumes a big GPU box with perfect cooling, your robot isn’t a robot—it’s a rolling server rack.

Underwater robots force compute discipline: efficient models, predictable latency, robust I/O. Industrial teams should adopt that same discipline early.

Practical moves:

- prefer smaller models with better data over large models with weak coverage

- use hardware-aware optimization (quantization, pruning where appropriate)

- design inference around deterministic timing (robots hate surprise latency)

2) Design for “repair at sea” (even if you’re on land)

Unema talks about fixing what breaks with limited resources aboard a ship. That’s not romantic—it’s a reliability strategy.

For industrial AI robotics, “repair at sea” translates to:

- modular electronics and sensors (fast swap)

- graceful degradation modes (keep operating safely when a camera goes blind)

- strong logging and black-box telemetry (so you can diagnose without guessing)

If you can’t service it quickly, your ROI model collapses.

3) Bandwidth limits make edge AI non-negotiable

Deep-sea robots share limited fiber capacity across video and instruments, and “every year new instruments consume more data.” That’s exactly what happens in modern automation: every new sensor, camera, and quality check adds data load.

Edge AI isn’t a buzzword here. It’s the only way to scale.

Human-in-the-loop is not a compromise—it’s a strategy

Key point: The most reliable autonomy is often a partnership: AI handles perception + stabilization; humans handle intent + edge cases.

On expeditions, Unema pilots the ROV while scientists watch video feeds and direct what to investigate. That workflow is an underrated model for industrial operations:

- Operators specify goals (“inspect these racks,” “scan this weld,” “collect these measurements”).

- AI handles the low-level execution (navigation, viewpoint selection, detection).

- Experts intervene when the environment violates assumptions.

I’ve found that teams get faster results when they stop chasing “no human involved” and start chasing fewer humans per robot with better tools.

What AI should automate first in remote operations

Whether it’s ocean exploration or remote industrial sites (mines, offshore platforms, large yards), prioritize AI that reduces operator cognitive load:

- Auto-stabilization and station-keeping (less manual correction)

- Collision avoidance and safe envelopes (fewer incidents)

- Target tracking (keep the subject centered while the operator decides)

- Automated data capture (consistent imagery/measurements, less rework)

- Anomaly surfacing (highlight what changed since last inspection)

These are the unglamorous wins that compound into real autonomy.

AI-driven perception underwater: why it’s harder than you think

Key point: Underwater perception is a stress test for vision AI—lighting, turbidity, backscatter, and domain shift are constant.

Many AI teams underestimate underwater perception because they assume a “camera is a camera.” Underwater, images are distorted by:

- low light and artificial illumination hot spots

- particulate backscatter (snowy noise)

- color absorption and shifting white balance

- motion blur from currents and vehicle vibration

That’s not just a computer vision problem; it’s a data strategy problem.

A practical dataset plan for harsh environments

If you’re deploying AI robotics in any hard-to-see environment (underwater, dusty warehouses, reflective factory floors), borrow this playbook:

- Collect data across missions/seasons/conditions, not one “good day”

- Label for failure modes, not just classes (blur, occlusion, glare, silt-out)

- Track performance by scenario slice (clear water vs. turbid; daylight vs. night ops)

- Add a human-review queue for uncertain detections to improve the dataset continuously

The goal is simple: reduce surprises. Robots fail in the gaps between your training distribution and reality.

What businesses can learn from Unema’s “idea to operations” loop

Key point: The fastest improvements happen when the same team designs, integrates, and operates the robot—because feedback is immediate.

Unema emphasizes the satisfaction of doing “all aspects of engineering—from idea to operations.” That’s also one of the most effective organizational structures for AI robotics.

If your AI team never sees the robot in the field, you’ll get:

- models optimized for benchmarks instead of mission outcomes

- brittle integrations

- slow debugging cycles

If your AI team owns operations feedback, you’ll get:

- better instrumentation and logs

- faster iteration on edge cases

- clearer ROI tracking (time saved, rework reduced, downtime avoided)

Metrics that matter (and actually drive ROI)

For underwater robotics, success might look like: more usable footage per dive, fewer aborted missions, faster identification of targets of interest. In industrial automation, use equivalents:

- First-pass yield improvement from vision inspection

- Mean time to recover (MTTR) after perception failures

- Autonomy minutes per operator hour

- Intervention rate per kilometer / per task

- Data usefulness rate (how much captured data is actionable)

If you can’t measure autonomy in operational terms, you’ll argue about it forever.

Where to go next if you’re building AI robotics for harsh sites

Key point: The next frontier isn’t “more AI.” It’s better system design: edge compute, robust comms, and workflows that scale.

Underwater exploration is expanding, and the same tech stack is starting to show up in commercial work: infrastructure inspection, environmental monitoring, offshore energy operations, and maritime security. Meanwhile, the design patterns are identical to those in logistics and manufacturing.

If your team is considering AI robotics for remote operations—or you’re upgrading existing robots with autonomy—here’s what I’d do next:

- Audit your constraints (bandwidth, power, compute, maintenance access)

- Pick one autonomy wedge that reduces operator load measurably

- Instrument everything (logs, confidence, context, failure capture)

- Build a data loop (review → label → retrain → redeploy)

- Design for field service from day one

The reality? Extreme environments don’t just “need better robots.” They force better engineering habits.

A useful north star: If your robot can succeed on a ship in the middle of the Pacific, it can probably succeed in a warehouse on a bad day.

As this AI in Robotics & Automation series keeps exploring real deployments, underwater ROV operations are a reminder that autonomy is rarely a single feature. It’s a stack of decisions—mechanical, electrical, software, and human workflow—built to survive reality.

If you’re evaluating AI robotics for your operation, what’s the first constraint you’d like the robot to handle without calling a human—bandwidth, perception, navigation, or recovery when things break?