AI spherical robots like RoboBall tackle sand, surf, rubble, and craters by removing orientation failures and adding smarter autonomy for harsh environments.

AI Spherical Robots: RoboBall and Extreme Terrain Ops

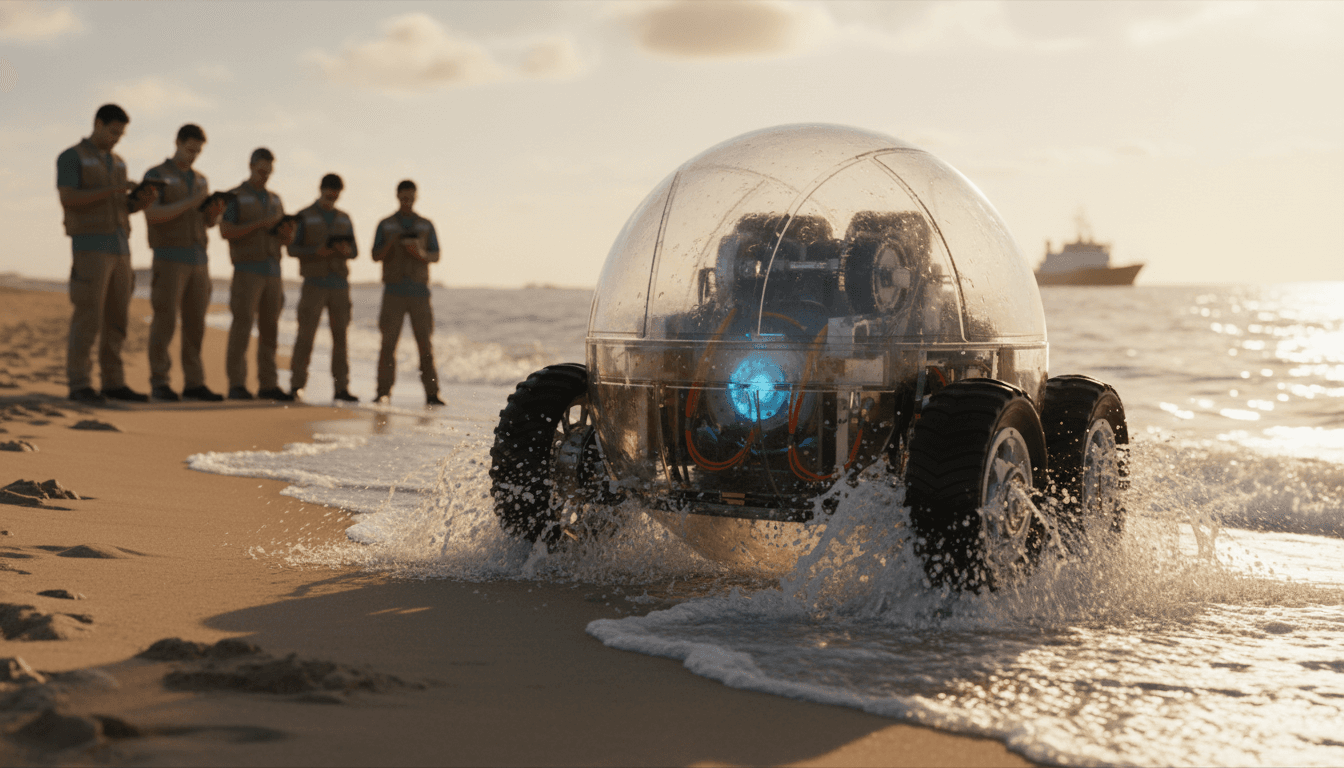

A six-foot sphere rolling out of surf and onto sand sounds like a stunt—until you remember how many real-world robots fail at exactly that moment. The “transition zones” (water-to-land, rubble-to-road, slope-to-flat) are where wheels spin out, legs slip, and expensive payloads end up sideways.

That’s why RoboBall—an idea first sketched at NASA in 2003 and revived at Texas A&M University’s Robotics and Automation Design Lab (RAD Lab)—is more than a quirky form factor. A spherical robot with no fixed top or bottom is a direct response to the ugliest physics problems in field robotics: tipping, snagging, and getting stuck. And when you pair that geometry with modern AI-enabled navigation, you get a platform that can realistically extend automation into places most robots still avoid.

This post is part of our “AI in Robotics & Automation” series, where we track how intelligence + rugged hardware expands what robots can do in manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, and service work. RoboBall is a clean example of that theme: better shape, smarter control, wider deployment.

Why spherical robots matter in real deployments

A spherical robot matters for one simple reason: it removes “orientation” as a failure mode. If your robot can’t flip over, you eliminate an entire category of recovery behaviors, operator interventions, and mission-ending accidents.

Traditional platforms generally trade off between:

- Wheels: efficient on predictable terrain, fragile in soft sand, loose gravel, or debris fields

- Legs: adaptable, but complex, power-hungry, and harder to seal against water and dust

- Tracks: robust, but still prone to getting hung up and often struggle at abrupt transitions

A sphere changes the interaction with the environment. There are fewer edges to catch. Contact forces distribute differently. And when the shell is compliant (the “robot in an airbag” concept behind RoboBall), it can absorb bumps that would destabilize a rigid chassis.

The hidden KPI: fewer “stuck events” per hour

Most teams optimize for speed or battery life. In field automation, the metric that quietly dominates cost is how often a robot needs help.

Every recovery event costs time, creates safety risk, and kills scalability. If you want robots deployed after hurricanes, in industrial yards, on beaches, or in planetary regolith, reducing the frequency of “we need a human to go get it” matters more than squeezing out another 5% of efficiency.

A spherical platform is opinionated hardware: it’s saying, “I’m built to keep moving when conditions stop being polite.”

RoboBall’s “robot in an airbag” design—what it enables

RoboBall’s core idea is straightforward: put the robot inside a protective spherical shell, so the system can roll in any direction without worrying about “upright” vs. “upside-down.”

At Texas A&M, two versions are being developed in parallel:

- RoboBall II (2-foot diameter): tuned for experiments—power monitoring, control algorithms, and rapid iteration

- RoboBall III (6-foot diameter): designed for payloads like sensors, cameras, and sampling tools, closer to mission-scale use

The team has already pushed RoboBall II to 20 mph, roughly half of its theoretical power output. That speed matters less as a headline and more as evidence of control authority: if you can command stable motion at high speed, you usually gain headroom for robust low-speed behaviors like climbing, turning in place, and resisting disturbances.

Water-to-land transitions: the beach test is a big deal

RAD Lab’s planned field trials on the beaches of Galveston focus on a deceptively hard requirement: buoyancy + traction + stability across a boundary.

The challenge isn’t only “can it float?” It’s:

- Can it maintain control when water drag changes the dynamics?

- Can it generate the right torque when sand yields under load?

- Can it avoid burying itself during the first few rotations onshore?

That combination is why “traditional vehicles stall or tip over” at abrupt transitions. A spherical robot that rolls out of water onto sand without caring about orientation is exactly the kind of platform that starts to look useful for coastal inspection, flood response, and amphibious surveying.

Where AI actually fits: autonomy on a rolling sphere

A sphere is mechanically elegant, but it doesn’t magically know where to go. The real ceiling on RoboBall-like systems is not the shell—it’s perception, planning, and control under uncertainty.

Here’s the practical AI stack that makes spherical robots viable in the field.

1) State estimation when your “front” constantly changes

Most mobile robots benefit from a stable body frame: the robot has a front, a top, a known orientation. A sphere doesn’t.

That pushes you toward sensor fusion that can tolerate continuous rotation and vibration:

IMUfor angular rates and acceleration- wheel/actuator telemetry from internal drive mechanisms

- visual-inertial odometry when cameras are feasible

- LiDAR or radar when conditions are dusty, dark, or smoky

AI helps by learning better priors for slip and drift, and by detecting when your estimator is lying (for example, when the robot is rolling but not translating because it’s stuck).

2) Terrain understanding: sand, mud, rubble, and the “soft ground” problem

Legged and wheeled robots both struggle on deformable terrain. Spherical robots do too—just differently.

A useful stance: treat terrain classification as a control input. If the robot recognizes “soft sand,” it can immediately shift behaviors:

- lower acceleration to avoid digging in

- change gait/torque profiles internally

- widen turns to reduce shear

- slow down and prioritize stability over speed

This is where machine learning can earn its keep: not by being fancy, but by being predictive. If the model can predict sinkage or slip probability from sensor cues, you stop reacting after you’re stuck.

3) Planning for non-holonomic-ish motion and constraints

Spherical locomotion often has constraints that don’t look like normal differential drive. AI planning can help by learning which maneuvers are reliable:

- “roll-and-yaw” patterns that keep the payload oriented

- recovery behaviors that rock the sphere to escape depressions

- safe descent strategies on steep slopes (relevant to crater walls)

In space exploration scenarios, autonomy isn’t optional. Communication delays make teleoperation painful, and line-of-sight drops quickly in rugged terrain. An autonomous spherical robot is appealing because it pairs passive stability (shape) with active intelligence (decision-making).

People also ask: Why not just use a rover with better wheels?

Better wheels help, but they don’t remove the biggest failure mode: loss of stability and orientation dependence. A rover still has a “wrong side up,” still has exposed components, and still tends to snag on obstacles that a sphere rolls over.

If the mission prioritizes reliability in chaotic environments over precision docking or payload manipulation, the sphere can be the right compromise.

The engineering reality: sealed robots are hard to maintain

RoboBall’s biggest strength—being sealed inside a protective shell—creates its most painful operational issue: maintenance becomes surgery.

Once everything is inside layers of wiring and actuators, quick fixes disappear. If a motor fails or a connector slips, you can’t open a hatch and swap a module. You disassemble, debug, and rebuild.

I’m opinionated here: if spherical robots are going to move from labs into real deployments, teams need to treat serviceability as a first-class requirement, not a “later” problem.

Practical design moves that reduce downtime

If you’re building rugged autonomous robots (spherical or not), these design patterns pay off:

- Modular internal pods: compute + power + actuation as swappable units

- Self-diagnostics by design: continuous health checks for motors, temps, battery impedance, sensor heartbeat

- Fault-tolerant behaviors: limp-home modes when a subsystem degrades

- Digital twin testing: replay field logs in simulation to isolate failure conditions

A sealed robot that can predict its own failure is far less scary to deploy.

Where RoboBall-style robots fit in automation beyond space

Space exploration is the headline, but the near-term market pull is on Earth. Spherical robots map nicely to sectors that share three traits: harsh environments, limited infrastructure, and high cost of human risk.

Disaster response and emergency services

The team’s vision of deploying a “swarm” after a hurricane is realistic because spheres can be dropped, rolled, and recovered with less precision than many platforms.

Concrete use cases:

- mapping flooded streets and debris fields

- checking under collapsed structures without sending in humans

- carrying cameras, thermal sensors, or air-quality sensors

Industrial inspection in hard-to-access areas

Think ports, coastal energy infrastructure, mining sites, and industrial yards.

A spherical robot can:

- traverse uneven ground near heavy equipment

- tolerate bump impacts and dust exposure

- carry sensor payloads for inspection routes

Environmental monitoring and coastal science

Galveston-style water-to-land missions point to routine operations:

- shoreline erosion surveys

- wetland monitoring

- beach safety assessments after storms

Automation here isn’t about replacing scientists. It’s about collecting better data more often—especially during the weeks when conditions are dangerous.

Student-led robotics is a lead indicator of what’s coming

One detail from the RoboBall story deserves attention: the autonomy given to the graduate student team. When researchers like Rishi Jangale and Derek Pravecek run the engineering decisions end-to-end, you get faster iteration and more honest learning.

It’s also a preview of the talent pipeline. The next generation of robotics engineers is being trained on real constraints:

- building control algorithms that survive outdoors

- debugging systems where access is limited

- designing for payload integration and mission outcomes

For organizations investing in AI in robotics and automation, this matters. The teams that win aren’t only the ones with strong models—they’re the ones who can integrate AI into hardware that keeps functioning when conditions get ugly.

What to do if you’re building robots for extreme environments

If RoboBall resonates with your application, here’s a practical checklist I’ve found useful for early-stage scoping. Treat it as a set of “go/no-go” questions.

- Define your failure budget: How many stuck events per 10 km (or per hour) are acceptable?

- Prioritize transitions: List your boundary conditions (water-to-land, gravel-to-mud, curb-to-sidewalk) and test them early.

- Make AI serve reliability: Use ML for slip prediction, anomaly detection, and terrain classification before fancy behaviors.

- Design service loops: Plan how the robot will be diagnosed, repaired, and redeployed in the field.

- Plan payload integration now: Cameras, LiDAR, samplers, comms—your geometry and power budget depend on it.

Robots that succeed outside the lab are usually the ones designed around operations, not demos.

The bigger point for AI in Robotics & Automation

RoboBall is a reminder that “smarter” isn’t always the first step. Sometimes the best progress comes from picking a shape that refuses to fail in common ways, then letting AI handle navigation and decision-making.

If you’re exploring AI-enabled robotics for logistics, inspection, or field service, watch projects like this closely. A spherical robot that can transition from water to sand, survive impacts, and carry sensors is the kind of platform that expands where automation can realistically operate.

The question worth asking next isn’t “Can we build a rolling sphere?”—that’s already happening. The next question is: What missions become economically viable when robots stop tipping over and start understanding their terrain?