AI makes autonomous vehicles smarter through imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and rigorous evaluation. Use the same playbook in robotics and automation.

How AI Makes Driverless Vehicles Smarter (Not Just Driverless)

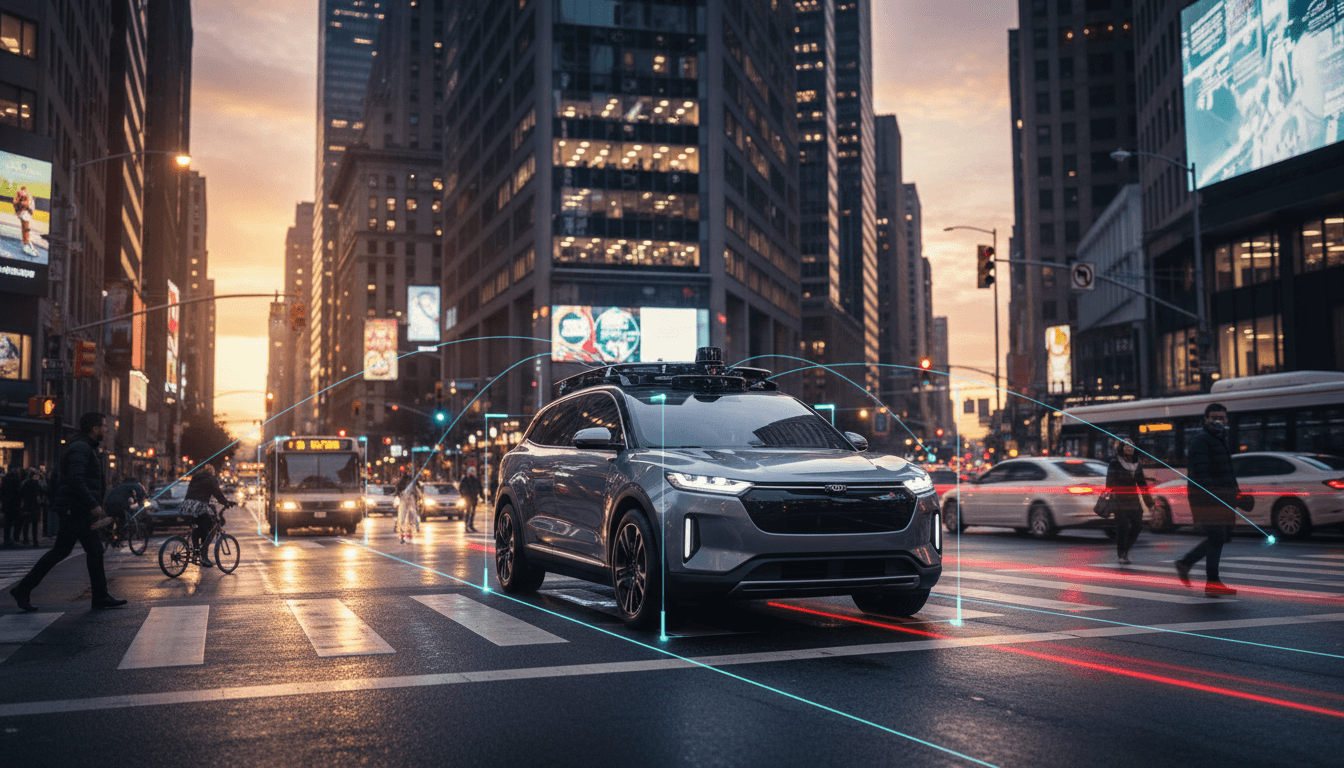

A driverless vehicle that only follows rules is still brittle. The real bar is higher: it has to handle messy reality—construction zones that weren’t on the map, a delivery van blocking a lane, an uncertain pedestrian, glare at sunset, and that one intersection where everyone behaves “creatively.” That’s why the most interesting progress in autonomous vehicles isn’t about removing the steering wheel. It’s about making the vehicle’s decision-making more adaptive, more robust, and more measurable.

In Robot Talk Episode 136, Claire spoke with Shimon Whiteson (Professor of Computer Science at the University of Oxford and Senior Staff Research Scientist at Waymo UK) about the machine learning methods behind smarter autonomy—especially deep reinforcement learning and imitation learning. If you work in robotics and automation—manufacturing, logistics, warehouses, field robotics—this conversation is more relevant than it sounds. Autonomous vehicles are basically robotics at scale: long-tail edge cases, safety constraints, and nonstop interaction with humans.

Here’s what’s actually making driverless vehicles smarter—and how you can borrow the same playbook for robots in industrial automation.

“Driverless” is the easy part; “smart” is the hard part

A vehicle can be “driverless” in a restricted sense (fixed route, perfect weather, simple environment). But smarter autonomous vehicles need to perform under uncertainty and still behave predictably.

Smarts in autonomy usually boils down to three capabilities:

- Perception with uncertainty awareness: the system doesn’t just label objects; it understands when it’s unsure.

- Planning that’s context-sensitive: it chooses actions based on intent, risk, and downstream consequences.

- Learning that improves behavior over time: it gets better from data without needing a human to re-code every corner case.

Whiteson’s research background—reinforcement learning (RL) and imitation learning (IL)—sits right at capability #3. And this matters beyond cars. The same learning challenges show up in:

- Autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) in warehouses navigating mixed traffic

- Robotic forklifts dealing with pallets placed “almost” correctly

- Last-meter delivery robots operating near pedestrians

- Industrial arms learning variable grasps from imperfect parts

If your automation system is stuck in “if-then” territory, you’re paying an edge-case tax forever.

Reinforcement learning: training policies, not rules

Reinforcement learning trains a policy—an action strategy—by optimizing for long-term outcomes. Instead of coding “do X when Y happens,” you specify objectives (safety, comfort, efficiency, rule compliance) and learn behaviors that meet them.

Why RL fits autonomous driving (and why it’s still hard)

RL matches autonomous driving because driving is:

- Sequential: every action changes the next situation.

- Interactive: other agents react to you.

- Multi-objective: safety beats speed, but speed still matters.

The hard part is that real-world driving is too safety-critical to do naive trial-and-error. So the practical question becomes: how do you get the benefits of RL without unsafe exploration?

The answer in modern autonomy tends to look like this:

- Learn primarily from simulation and logged data

- Use constraints and safety filters

- Validate with strong offline metrics and staged deployments

That same pattern is becoming the default in robotics and automation. Most companies I talk to want learning-based control, but they don’t want a robot “learning” by breaking fixtures or risking people.

What “smarter” looks like in RL terms

Smarter policies don’t just drive; they manage trade-offs well.

A mature RL setup for autonomous vehicles typically optimizes a weighted reward that encodes things like:

- Collision risk and near-misses

- Lane discipline and traffic rule adherence

- Passenger comfort (jerk, hard braking)

- Efficiency (time, energy)

- Social driving norms (not bullying merges, not freezing forever)

That’s also the right framing for industrial robotics: stop optimizing a single KPI in isolation. A warehouse AMR that’s “fast” but causes humans to constantly step aside isn’t successful automation—it’s a safety incident waiting to happen.

Imitation learning: learning from good examples (and fixing the gaps)

Imitation learning trains models from demonstrations—usually human driving or expert policies—so the system starts competent instead of random. In autonomous vehicles, this often means learning from large-scale logged driving data.

The practical advantage of imitation learning

IL gives you something incredibly valuable: reasonable behavior on day one.

For AVs, that matters because:

- Human driving data covers a broad distribution of normal scenarios

- It encodes subtle norms (like how merges actually work)

- It reduces the amount of risky exploration required

For robotics teams, IL is often the fastest path to a useful baseline, especially when you already have operators who can do the job.

The catch: imitation alone won’t cover the long tail

Imitation learning struggles in exactly the places where autonomy needs to be strongest:

- Rare events (a mattress falls off a truck)

- Unusual layouts (temporary lane shifts)

- Distribution shifts (new city, new weather patterns)

This is where RL often re-enters the picture: use imitation learning to get competent, then use reinforcement learning (with constraints) to get robust.

If you’re building robots for logistics and transportation, you can mirror this:

- IL baseline from teleop or expert demonstrations

- RL fine-tuning in simulation for edge cases

- Conservative deployment with monitoring and rollback

The hidden engine: evaluation, data, and “what do we optimize?”

Most autonomy programs don’t fail because the neural net “isn’t fancy enough.” They fail because:

- Their data strategy is weak

- Their evaluation metrics don’t match real-world risk

- They can’t iterate safely

Offline evaluation is the bottleneck nobody brags about

In driverless systems, you can’t ship updates like a typical SaaS product. You need to prove the new model is safer before it hits public roads.

That means serious investment in:

- Scenario-based evaluation: curated test cases that represent real failure modes

- Counterfactual analysis: “what would this policy have done here?”

- Regression testing: ensuring you didn’t fix merges but break unprotected left turns

This applies directly to robotics and automation. If your robot’s learning update improves pick rate by 4% but increases near-collisions in shared aisles, you’ve lost the plot.

A stance I’ll defend: If you can’t evaluate it, you can’t automate it responsibly.

Reward design is product design

In RL, reward design isn’t a math detail—it’s product intent.

If your reward emphasizes speed too much, you get aggressive behavior. If you over-penalize risk, you get freezing and indecision.

In industrial settings, reward design maps to:

- Throughput vs. congestion

- Energy vs. cycle time

- Quality vs. scrap

- Autonomy vs. need for human intervention

Teams that treat this as a leadership-level product decision (not a research intern’s spreadsheet) usually ship safer systems.

What AV learning teaches robotics and automation teams

Autonomous driving is an extreme environment for AI: open world, human interaction, and safety constraints. That’s why it’s such a good reference case for the broader “AI in Robotics & Automation” series.

1) Start with a hybrid stack, not ideology

Pure end-to-end learning is tempting. Pure rules are comforting. In practice, most production systems mix:

- Learning-based perception and prediction

- Planning with explicit constraints

- Safety monitors (hard limits, redundancy)

Hybrid isn’t a compromise. It’s how you meet safety and reliability goals while still improving.

2) Treat simulation as an engineering discipline

Simulation isn’t just for demos. It’s where you manufacture edge cases.

Good simulation programs have:

- Scenario generation (including rare events)

- Domain randomization (lighting, friction, sensor noise)

- Clear sim-to-real validation gates

If you’re deploying robots in logistics, you can—and should—use simulation to test facility changes, peak-season congestion, and mixed fleets.

3) Make “disengagements” and “near misses” first-class metrics

AV teams track interventions because it’s a leading indicator of risk. In industrial automation, equivalents include:

- Emergency stops

- Human overrides

- Near-collision events from proximity sensors

- Repeated replans or deadlocks

If you only track throughput, you’ll optimize straight into operational chaos.

4) Data flywheels require governance, not just storage

Everyone wants a data flywheel. Few teams build the governance that makes it work:

- Data labeling standards

- Bias and coverage audits

- Privacy and retention rules

- Clear ownership of “what gets collected and why”

This is especially timely heading into 2026 budget planning: leadership teams are deciding whether AI initiatives are “R&D experiments” or operational infrastructure. The difference is governance.

Quick FAQ: the questions leaders actually ask

Is reinforcement learning used in real autonomous vehicles?

Yes—especially in simulation-heavy workflows and for specific decision-making components. But it’s typically paired with constraints, safety filters, and extensive evaluation.

What’s the biggest blocker to smarter autonomous driving?

Not model size. Validation, edge-case coverage, and measurable safety are the blockers.

Can these methods help warehouse robots and AMRs?

Directly. The same IL→RL progression and simulation-first iteration model fits warehouse navigation, task planning, and multi-robot coordination.

Where to go next if you’re building smarter robots

Smarter autonomy isn’t about chasing a single algorithm. It’s about building a system that can learn, be evaluated, and be trusted.

If you’re responsible for robotics and automation—especially in logistics and transportation—steal what works from autonomous driving:

- Use imitation learning to reach competent behavior quickly

- Use reinforcement learning to improve robustness in simulation

- Invest early in evaluation infrastructure so every update is safer than the last

This post is part of the AI in Robotics & Automation series because AVs are a preview of what’s coming for every autonomous machine: more learning, more interaction with people, and higher expectations of safety.

What would your robots do better next quarter if you treated evaluation and data strategy as seriously as model training?