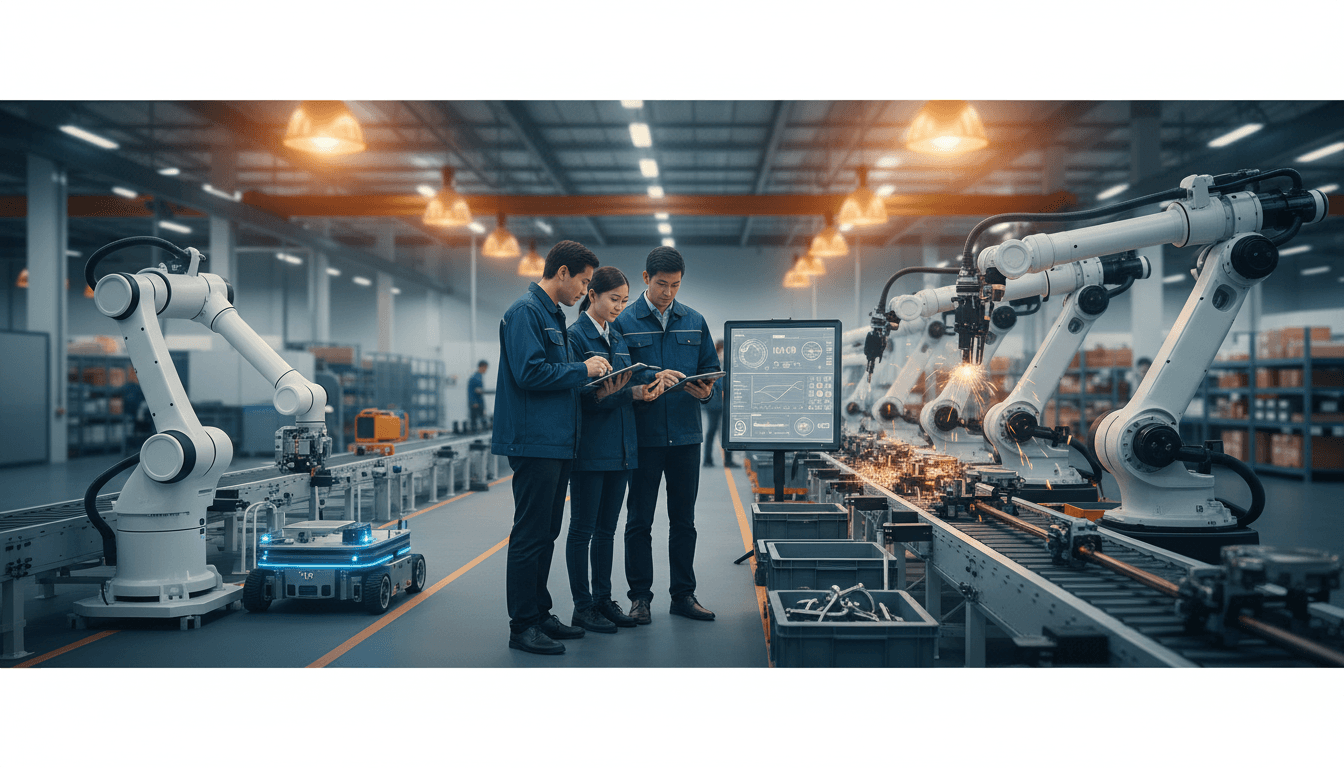

AI robotics research only matters when it ships. Learn the interface-first playbook for deploying AI-driven robots in manufacturing, logistics, and healthcare.

Most robotics programs don’t fail in the lab. They fail in the handoff.

A team gets a clever demo working—then reality shows up: procurement, safety cases, integration with messy legacy systems, unpredictable users, and an ops team that just wants the line to keep running. The gap between “paper-worthy” and “production-worthy” is where promising robotics research goes to stall.

That’s why the conversation in Robot Talk Episode 131 with Edith‑Clare Hall (University of Bristol PhD student, Frontier Specialist at ARIA, and leader of Women in Robotics UK) hits a nerve for anyone building AI-driven robotics in manufacturing, logistics, or healthcare. Hall’s work sits exactly at the interfaces where systems collide—robot to environment, autonomy to safety, research to deployment. And she’s blunt about what it takes to accelerate breakthroughs without losing the thread of real-world impact.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, where the practical question is always the same: what makes intelligent robots deliver measurable value outside the demo room? Hall’s perspective gives a useful answer—then we’ll push it further with concrete patterns you can apply in your organization.

Why “AI robotics research” stalls at the system interfaces

The fastest way to slow a robotics project is to treat it as a single product instead of a stack of interconnected systems.

Robots don’t operate in isolation. They sit inside workflows—often safety-critical ones—with humans, tools, software, compliance requirements, and unpredictable environments. Hall focuses on these interfaces, because they’re where autonomy tends to break: perception meets lighting changes; planning meets production variability; a learned policy meets a safety envelope.

The interface problem is where autonomy gets expensive

If you’ve ever scoped an automation project, you know the hidden cost isn’t “AI vs. no AI.” It’s the integration work:

- Perception-to-action latency that’s fine in a lab, but causes missed picks on a conveyor.

- Data drift when your warehouse adds new SKUs, packaging, or seasonal demand spikes.

- Safety constraints that invalidate a policy that looked great in simulation.

- Human factors—operators bypassing a system that slows them down, even if it’s “accurate.”

AI can make robots more capable, but capability without interface discipline turns into fragile automation.

What Hall gets right: close the research-to-deployment loop early

Hall’s background includes building bespoke robotic systems to support people with progressive conditions like motor neurone disease (MND). Assistive robotics forces an uncomfortable level of honesty: if it’s unreliable, the user pays the price immediately.

That mindset translates cleanly into industrial automation: the robot isn’t the hero—the workflow is. And workflows punish brittle autonomy.

ARIA’s model: fund speed, but demand a deployment path

A lot of organizations say they want “moonshots,” but they fund them like slow academic projects or like short-term product increments. ARIA exists to do neither. It’s designed to accelerate scientific and technological breakthroughs while staying anchored to outcomes.

Hall works at ARIA as a technical generalist, which matters more than it sounds. In AI robotics, breakthroughs often come from connecting fields that don’t normally plan together—controls with machine learning, safety engineering with data pipelines, human-centered design with autonomy.

The better yardstick: time-to-proof, not time-to-paper

If your goal is AI in robotics and automation that drives adoption, measure progress with milestones that industry recognizes:

- Time-to-first reliable pilot (not first demo)

- Mean time between interventions (how often humans have to rescue the robot)

- Integration surface area (how many systems and teams must touch the solution)

- Total cost of ownership (TCO) assumptions (maintenance, calibration, retraining, spares)

A robot that needs constant “AI babysitting” is just a very expensive intern.

What “accelerating breakthroughs” looks like in practice

Acceleration isn’t about pushing teams to code faster. It’s about removing the blockers that keep autonomy trapped in prototypes:

- Faster access to testbeds (factories, warehouses, clinics)

- Clear safety and assurance pathways

- Shared infrastructure for data capture and labeling

- Procurement routes that don’t punish experimentation

If you want robots that ship, you need to treat deployment as a first-class research constraint.

Where AI is actually paying off in robotics right now

AI is no longer just a perception add-on. The value is showing up across the stack—especially when paired with disciplined engineering.

Manufacturing: robustness beats novelty

In manufacturing, the winner isn’t the fanciest model. It’s the system that stays stable across shifts, suppliers, and product variants.

AI-driven robotics is paying off in:

- Adaptive picking and placement when part presentation varies

- Anomaly detection for quality checks where “defect” is visually subtle

- Predictive maintenance that uses robot telemetry to prevent downtime

The pattern I’ve seen work: keep the autonomy bounded. Use learning for the uncertain pieces (vision, classification, grasp selection), while keeping motion and safety constraints explicit.

Logistics: the real bottleneck is exception handling

Warehouses are full of edge cases: damaged cartons, mixed totes, barcodes that don’t scan, half-collapsed pallets. AI helps most when it reduces exceptions per hour.

High-ROI uses include:

- Vision-based dimensioning and identification for irregular items

- Dynamic slotting and routing based on demand and congestion

- Human-in-the-loop autonomy where the robot escalates cleanly

If your autonomy can’t explain what it needs from a human (a photo, a confirmation, a re-grasp), it’s not ready for scale.

Healthcare and assistive robotics: trust is the product

Hall’s MND-related work highlights a core truth: in healthcare robotics, accuracy isn’t enough—predictability builds trust.

AI-enabled robotics can support:

- Assistive manipulation (fetch, carry, simple interactions)

- Rehab and mobility support with adaptive control

- Monitoring and triage support where robots gather data safely

But the bar is higher. You need clear failure modes, intuitive handovers, and privacy-by-design data practices.

A practical playbook: how to turn AI robotics into deployed automation

The reality? It’s simpler than you think, but it’s not easy. You need a repeatable approach that respects system interfaces.

1) Start with a workflow that has a measurable pain signal

Pick a task where the business already tracks loss:

- Scrap and rework rate

- Downtime minutes per shift

- Cost per pick / per unit handled

- Nurse time spent on non-clinical tasks

If there’s no baseline, your “AI robotics ROI” story will collapse during rollout.

2) Design for interventions, not perfection

Assume the robot will need help. Design the help pathway:

- What triggers an escalation?

- Who gets notified?

- How does the operator resolve it in under 30 seconds?

- What data gets logged automatically for retraining?

This is where many AI robotics deployments become economically viable: quick recoveries keep throughput stable.

3) Treat data as a production subsystem

If you’re using machine learning, your robot isn’t just a robot—it’s a data product.

Operational requirements you should document upfront:

- Data capture (what, when, how much)

- Labeling strategy (manual, weak supervision, synthetic data)

- Retraining cadence (monthly? per release?)

- Drift detection signals (new SKUs, lighting, tooling changes)

If your data pipeline is “someone exports logs when things go wrong,” you’re not doing AI robotics—you’re doing hope.

4) Keep safety explicit, even when learning is involved

Don’t hide safety inside a black box. Safer autonomy usually looks like:

- Learned perception + rule-based safety layers

- Learned grasp suggestion + force/torque and speed limits

- Learned planning proposals + verification or constraint checking

In safety-critical environments, the architecture matters as much as model accuracy.

5) Build a bridge role between research and operations

Hall’s career path implicitly points to a missing role in many teams: someone who can translate across autonomy, hardware constraints, and real-world workflows.

Call it a frontier specialist, systems integrator, or robotics product engineer—the title doesn’t matter. The function does:

- Own requirements that span AI, robotics, safety, and ops

- Protect test time in real environments

- Prevent “demo-driven development”

If you don’t staff this role, you’ll pay for it in integration churn.

People also ask: common questions about AI-driven robotics research

What’s the difference between robotics research and robotics automation?

Robotics research proves new capabilities under controlled assumptions. Robotics automation is the engineering work that keeps those capabilities reliable under real constraints—throughput, safety, maintenance, and variability.

Where should AI sit in a robotics stack?

AI works best where uncertainty is high (vision, classification, grasp selection, anomaly detection). Keep safety and hard constraints explicit, and don’t let learning be the only layer between the robot and a person.

How do you evaluate an AI robot beyond accuracy?

Use operational metrics: interventions per hour, uptime, cycle time variance, recoveries, and how quickly the system adapts to change (new products, new environments, new users).

The stance: stop fetishizing autonomy—optimize for adoption

Full autonomy makes for great demos. Adoption makes for great businesses.

Hall’s focus on interfaces and real-world deployment is the healthiest kind of pressure on the field. If we want AI in robotics to matter in 2026 planning cycles—budgeting, staffing, facility design—teams need to build systems that degrade gracefully, integrate cleanly, and earn trust over months, not minutes.

If you’re evaluating an AI robotics initiative for manufacturing, logistics, or healthcare, start by mapping the interfaces: data, safety, ops handoffs, and exception handling. That’s where wins compound.

If you want a second set of eyes on your deployment plan, I’d suggest a simple next step: write a one-page “autonomy contract” for the task—what the robot will do, what it won’t do, how it asks for help, and how you’ll measure success after 30 days. Then build from there.

What interface in your current automation stack is the real bottleneck: data, safety assurance, integration, or operator adoption?