Drone landings at 110 km/h and ROS-MCP-Server show where AI in robotics is headed: robust hardware, safer AI control, and faster automation deployment.

Drones Landing at 110 km/h: AI Meets Real-World Robotics

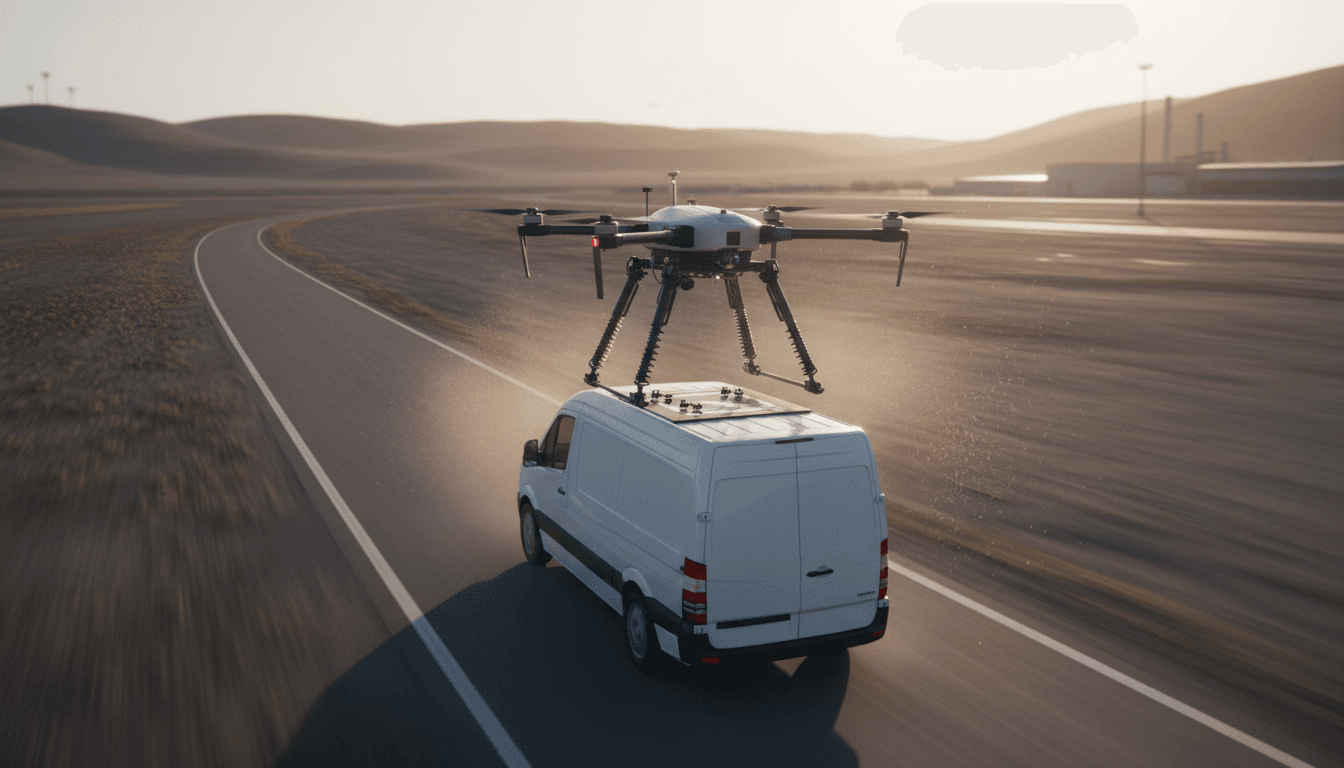

A drone touching down on a vehicle moving at 110 km/h isn’t a flashy trick—it’s a stress test for everything that breaks robots in the real world: wind gusts, timing errors, vibration, uncertain surfaces, and messy sensing. When a team can make that landing repeatable, they’re not just solving a “drone problem.” They’re proving a broader point that keeps showing up across robotics right now: the winners are the systems that combine smart software with forgiving hardware and clean interfaces.

That theme runs through this week’s robotics highlights: a high-speed drone landing system built around robust contact dynamics; an open-source bridge (ROS-MCP-Server) that helps AI models talk to robots in “robot language”; assistive robotics designed for daily life, not demos; and cobots hitting maturity as they become intelligent partners on the shop floor.

This post is part of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, and it’s focused on one practical question: What’s changing in robotics that actually makes deployments easier in 2026—and what should operators, integrators, and automation leaders do about it?

High-speed drone landings: the real innovation is robustness

The core breakthrough in the showcased landing system is simple to describe and hard to engineer: land a drone on a moving vehicle at highway speeds while staying stable through imperfect timing and unpredictable airflow.

What makes this notable is the design philosophy. Instead of betting everything on perfect perception and perfect control, the system expands the “landing envelope” with two very physical ideas:

- Lightweight shock absorption to handle impact and alignment error

- Reverse thrust to help the drone “stick” the landing and cancel relative motion

Why this matters for logistics and field operations

If you’re thinking about drone delivery, inspection, or emergency response, the moving-vehicle landing is more than convenience. It changes operational math.

A reliable moving landing means you can move the base station instead of forcing the drone to return to a fixed pad. That creates options like:

- Mobile replenishment for long-range inspection (power lines, rail corridors, pipelines)

- Intercept-and-recover workflows for public safety (the vehicle meets the drone where it finishes)

- Warehouse-to-yard handoff in large logistics sites (drone returns to a moving tug or cart)

The biggest bottleneck in many drone programs isn’t flight—it’s the last 10 seconds: recovery, battery swap, data offload, and redeploy. Improve that step and you improve everything around it.

Where AI actually fits in (and where it doesn’t)

A lot of teams over-credit AI for physical reliability. Here’s what I’ve found to be true in real deployments: AI helps most when it reduces the precision required from everything else.

In a system like high-speed landing, AI typically earns its keep in three places:

- State estimation under nasty conditions (gusty wind, vehicle vibration, partial occlusion)

- Adaptive control tuning across different vehicle speeds and turbulence profiles

- Anomaly detection that knows when to abort and go around

But the unsung hero is often mechanical design. Shock absorbers and reverse thrust don’t need “confidence intervals.” They work even when sensors are a little wrong.

Robust robotics isn’t about perfect autonomy. It’s about building systems that stay safe and useful when the world refuses to cooperate.

“AI talking to robots” is getting practical: ROS-MCP-Server

A second highlight points at a different friction point: robot software integration. The open-source initiative ROS-MCP-Server aims to connect AI models (think modern LLMs) to robots via ROS using the Model Context Protocol (MCP).

Here’s the direct value: it standardizes how an AI assistant discovers robot capabilities and interacts with multiple ROS nodes without bespoke glue code for every project.

Why this is a big deal for automation teams

Most companies don’t fail at robotics because the robot can’t move. They fail because:

- Every deployment becomes a one-off integration project

- Knowledge lives in one engineer’s head

- Small changes (a new gripper, new camera, new conveyor) cause weeks of rework

A tool like ROS-MCP-Server targets that reality. When an AI model can be given structured access to:

- robot state topics

- command/action interfaces

- sensor streams

- task constraints

…you get a new layer of interaction: natural-language intent → validated robot actions.

Done well, this doesn’t replace engineers. It changes the workflow so engineers spend less time on repetitive scaffolding and more time on the parts that matter: safety constraints, calibration, edge cases, throughput.

Practical use cases (beyond chatty demos)

If you’re running a robotics program, the highest ROI applications are surprisingly unglamorous:

- Faster commissioning: “Move to inspection pose A, then B, then C” becomes a reproducible macro that’s logged and versioned.

- Operator-friendly recovery: “Clear cell, re-home joints, re-try last pick with lower speed” can be guided through guarded steps.

- Cross-robot standardization: common task vocabulary across different robot arms and mobile platforms.

The key is governance: AI should be powerful, but boxed in.

A safety stance worth adopting

If you take one policy recommendation from this post, take this: no AI-to-robot bridge should execute unconstrained free-form commands on real hardware.

A safer architecture looks like:

- LLM proposes a plan

- System validates against a whitelist and safety constraints

- Human approval for high-risk actions (or a “safe mode” sandbox)

- Execution with continuous monitoring and automatic aborts

This approach makes AI in automation deployable without pretending the world is deterministic.

Assistive robotics is shifting from “lab impressive” to “daily usable”

The assistive robot Maya (designed for wheelchair integration) is a reminder that robotics success is often about fit more than flash.

The design details mentioned—optimized kinematics for stowing, ground-level access, and compatibility with standing functions—signal a mature engineering mindset: people don’t live in controlled demos. They live around door frames, kitchen counters, elevator gaps, crowded clinics, and imperfect routines.

What AI adds to assistive robots—when done responsibly

Assistive robotics is where AI has to be both useful and trustworthy. The best applications tend to be:

- Intent inference: recognizing what a user is trying to do from partial input

- Shared autonomy: the user guides, the robot handles fine motion and collision avoidance

- Personalization: adapting to a user’s reach, strength, preferences, and environment

But the bar is higher here than in a warehouse. A failed pick is downtime; a failed assist can be harm. So the engineering pattern that wins is the same as the drone landing: robustness first, intelligence second.

In healthcare and accessibility, reliability isn’t a feature—it’s the product.

Cobots at 20: the market matured, and expectations changed

Universal Robots’ 20-year milestone is a useful checkpoint. Collaborative robots proved that many automation tasks don’t require cages, massive footprints, or specialized programming teams.

Now the expectation is shifting again: cobots shouldn’t just be “easy to deploy.” They should be easy to adapt.

The new baseline for cobot deployments

If you’re buying cobots in 2026, I’d argue these are table stakes:

- Vision-assisted picking/placing with rapid changeover

- Simple operator flows for recipe changes and shift handoffs

- OEE-aware monitoring (not just “robot is running,” but “cell is productive”)

- Human-safe recovery behaviors and clear fault explanations

AI slots into this as a force multiplier for changeovers and troubleshooting—especially when paired with solid constraints and well-instrumented cells.

Real-to-sim, humanoid demos, and why “fun videos” still matter

The RSS roundup also nods to a trend that’s quietly reshaping robotics R&D: real-to-sim pipelines. For years, the mantra was sim-to-real—train in simulation, deploy in reality. The reality in 2025–2026 is more blended:

- capture real robot data

- build better simulators from that data

- train policies that reflect real contact and sensor quirks

This is especially relevant for contact-rich behaviors (hands, feet, manipulation) that show up in humanoid demos—like moonwalking legs or “dancing” robotic fingers. Sure, some of it is parody and showmanship, but the underlying point is serious: dexterity is a data problem and a modeling problem.

And even the silly clips (tennis balls underfoot, tic-tac-toe against a robot arm) have value: they expose the gap between controlled capability and messy reality. Good teams use that gap as a roadmap.

What automation leaders should do next (a practical checklist)

If your job is to ship robots into facilities—not just watch demos—here’s a set of concrete moves that align with where AI in robotics is headed.

1) Favor systems designed for “bad days”

When evaluating vendors or internal prototypes, ask:

- What happens with a 10% timing error?

- What happens with a gust, glare, or vibration spike?

- Is there mechanical forgiveness (compliance, damping) or is it all software?

High-speed drone landing tech is impressive because it’s explicitly built around these failure modes.

2) Treat AI-to-robot interfaces as production software

If you’re experimenting with tools like ROS-MCP-Server or any AI orchestration layer:

- define a command whitelist

- log every proposed and executed action

- require explicit state checks before motion

- implement abort conditions and test them regularly

You’re not installing a chatbot. You’re installing a control surface.

3) Measure success with cycle time, recovery time, and changeover time

Accuracy matters, but ROI often lives in:

- how quickly you recover from faults

- how fast you can swap SKUs

- how little expert intervention is needed

That’s where AI assistants—properly constrained—can create real gains.

Where this is going in 2026

High-speed drone landings and AI-to-ROS bridges look unrelated at first glance. They’re not. They both point to the same direction: robots are becoming operational systems, not isolated machines.

One path is physical robustness (shock absorption + thrust control so contact isn’t terrifying). The other is software interoperability (AI models that can reason over robot context safely). Put them together and you get the next wave of AI-driven automation: machines that can handle the variability you used to assign to humans.

If you’re building an AI in Robotics & Automation roadmap for 2026, a good question to pressure-test your strategy is this: Where are you still requiring perfect conditions—and what would it take to make your robots succeed when conditions are merely “good enough”?