AI prosthetic hands can regulate grip pressure in real time using tactile sensing and machine learning—making daily tasks safer, easier, and more natural.

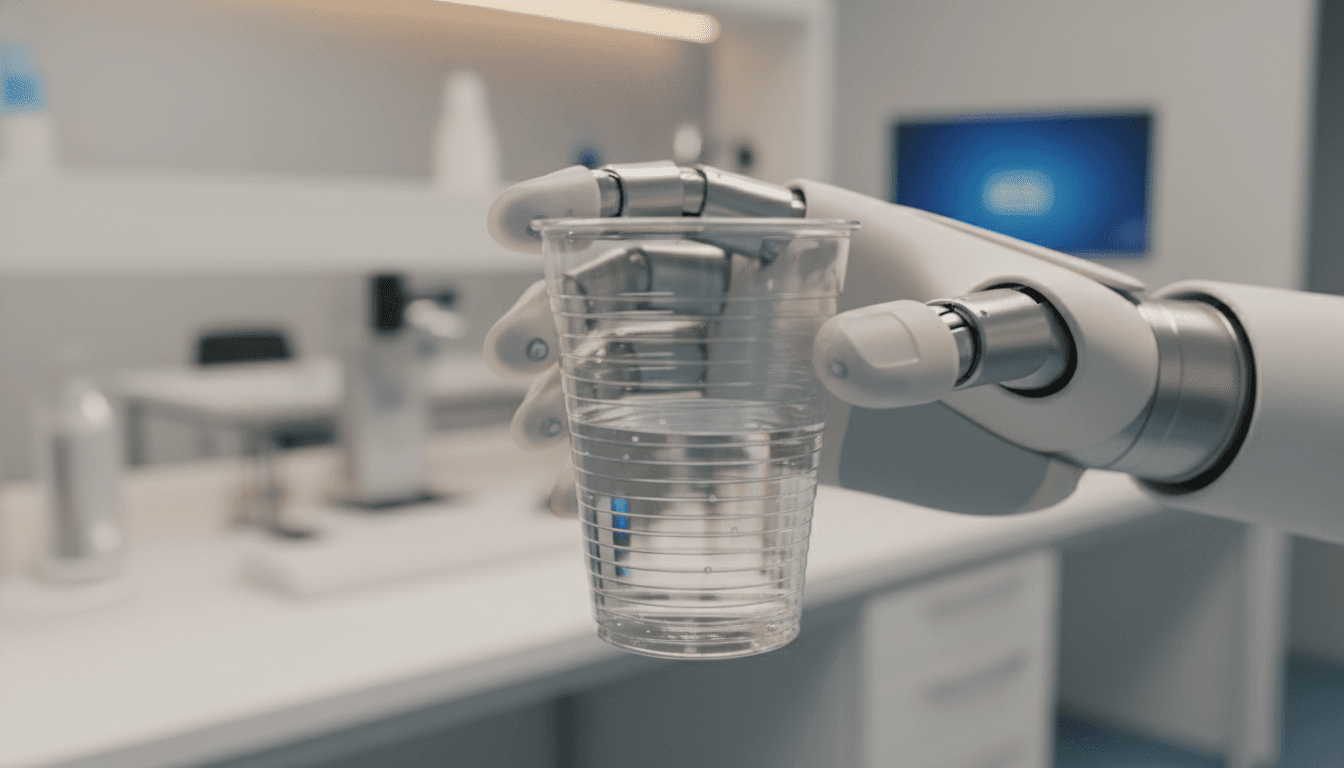

AI Prosthetic Hands That Grip Safely, Like Humans

Most prosthetic hands don’t fail because they’re weak. They fail because they’re uncertain.

If you’ve ever watched someone with an upper-limb prosthesis handle a paper cup, a slippery bottle, or a loved one’s hand, you’ve seen the same problem: how do you apply enough force to be secure, but not so much that you crush, spill, or hurt? That uncertainty is exhausting for users—and it’s a major reason many advanced hands still feel “robotic” in daily life.

A Johns Hopkins team demonstrated a prosthetic hand that tackles this head-on: it can identify what it’s gripping and regulate squeeze pressure in real time, using a hybrid soft-rigid structure, layered tactile sensors, and machine learning that turns sensor readings into nerve-like feedback. It’s a clean example of what this “AI in Robotics & Automation” series is really about: intelligence at the point of contact, where robots meet the messy physical world.

Why “safe grip” is the real prosthetics bottleneck

The direct answer: grip control is hard because the world is variable, and hands need fast feedback loops.

A prosthetic can have strong motors and decent mechanics, but without reliable touch feedback, users compensate by:

- Using vision constantly (“Am I slipping?”)

- Avoiding fragile objects

- Over-gripping for safety (which causes crushing or fatigue)

- Under-gripping (which causes drops)

Human hands solve this with dense tactile sensing and reflex-like control. Your fingertips detect micro-slips and texture; your nervous system reacts in milliseconds.

The robotics lesson: force control beats force capacity

Here’s the stance I’ll take: a prosthetic hand that can precisely regulate 10–20 N of force is more useful than one that can hit 100+ N without fine feedback.

In robotics terms, this is about closed-loop force control and state estimation:

- Force control: adjust actuation based on measured contact forces

- State estimation: infer what you’re touching (hard/soft, stable/slipping) from partial signals

That second piece—inferring state—is where AI earns its keep.

What Johns Hopkins built (and why the design matters)

The direct answer: they combined soft fingertips, a rigid internal skeleton, tactile sensor layers, and AI-driven sensory processing to regulate grip.

In experiments, the hand reportedly manipulated 15 different objects, including delicate stuffed toys and a flimsy plastic cup filled with water, without denting or damaging them. That range matters because it signals robustness across:

- Compliance differences (toy vs metal bottle)

- Geometry differences (pineapple vs box)

- Fragility differences (plastic cup vs cardboard)

Hybrid soft–rigid mechanics: closer to how real hands behave

A fully rigid robotic gripper needs perfect sensing and control to avoid damage. A fully soft hand can struggle with precision and load.

A hybrid approach splits the difference:

- Rigid skeleton (3D-printed): provides structure and repeatable kinematics

- Soft polymer fingers: increase contact area and tolerance to positioning errors

- Air-filled joints (pneumatic actuation): enable compliant motion and safer interaction

This mirrors a broader trend in medical robotics: mechanical compliance reduces the burden on control software, which improves safety and user trust.

Layered tactile sensors: more signal, less guessing

Tactile sensing isn’t one sensor—it’s a stack of signals. The reported design uses three layers of bioinspired tactile sensors, giving richer inputs than a single force sensor at the wrist.

That’s crucial because many “smart” prostheses still operate like this:

- User commands close/open (via EMG)

- Hand closes until a threshold

- Hope the threshold works for whatever object is present

Layered sensors allow discrimination between:

- Initial contact vs full grasp

- Stable hold vs slip onset

- Hard vs compliant materials

Where the AI fits: translating touch into “nerve language”

The direct answer: machine learning processes fingertip sensor data into signals that can be delivered as naturalistic sensory feedback via electrical nerve stimulation.

There are two AI jobs happening here:

- Signal conditioning and feature extraction (turn messy sensor streams into stable representations)

- Mapping representations to feedback (so the user’s nervous system receives meaningful cues)

This isn’t “AI for AI’s sake.” It’s a practical control problem: tactile sensors generate high-dimensional, noisy data. If you push raw signals to a user (or even to a controller), you get poor interpretability and inconsistent behavior.

The important shift: from “open-loop grasp” to adaptive grasp

A lot of myoelectric prostheses are effectively open-loop: the user commands motion, but doesn’t get enough feedback to modulate grip naturally.

An adaptive loop looks more like:

- Intent input: EMG suggests grasp type/close speed

- Contact sensing: tactile layers detect pressure distribution and slip

- AI inference: estimate object properties and risk of damage/slip

- Controller action: adjust pressure and finger motion

- User feedback: deliver nerve-like cues to reduce visual dependence

That’s the same architecture we want in service robots and warehouse manipulators: intent/plan + tactile + inference + correction.

EMG control plus low-cost hardware: a practical detail that matters

The prototype is controlled using EMG signals, captured with a consumer gesture-control armband and passed to an Arduino microcontroller for pneumatic actuation.

This matters for one reason: it shows the intelligence is doing the heavy lifting, not exotic hardware. When teams can prototype advanced behaviors with relatively accessible components, translation to product becomes more realistic.

What this signals for healthcare robotics (and for buyers)

The direct answer: AI-enabled tactile control is moving prosthetics from “tools” to “embodied devices” that users can trust.

If you’re a clinic, rehab center, or med-device team evaluating next-gen prosthetics, look beyond “degrees of freedom” and ask sharper questions:

Evaluation questions that actually predict real-world success

- Slip response time: How quickly does the system detect and correct micro-slip?

- Fragility handling: Can it pick up thin plastic, paper cups, soft fruit?

- Consistency across objects: Does it need per-object tuning?

- User cognitive load: Does the user still need to visually monitor every grasp?

- Feedback quality: Is sensory feedback distinguishable and learnable over weeks?

I’ve found that many pilots focus on demo-friendly tasks (like grasping a block). Real adoption comes from boring daily wins: carrying groceries, holding a child’s hand, washing dishes, handling winter gloves and wet surfaces.

Seasonal relevance: winter objects are a real stress test

In December, grip control gets harder in the real world:

- Condensation on bottles and mugs

- Gloves reducing residual limb EMG clarity

- Cold surfaces changing friction

- More frequent handling of fragile items (ornaments, glassware)

Systems that can infer slip and adjust pressure aren’t just “nice.” They address the exact failure modes that show up during holiday routines.

The broader automation connection: this is the same tech humanoids need

The direct answer: prosthetic-grade tactile intelligence is directly transferable to humanoid and industrial manipulation.

Robotics teams building warehouse pickers, lab automation, or humanoids often obsess over vision and planning. Vision is necessary—but touch is what prevents expensive mistakes.

The manipulation stack is converging:

- Prosthetics need safe human interaction

- Service robots need safe home interaction

- Industrial cobots need safe shared workspaces

In all three, tactile sensing plus AI inference enables:

- Lower grasp force without dropping

- Better handling of deformable items (food, packaging)

- Reduced damage rates (and therefore reduced cost)

If you’re in manufacturing or logistics, the takeaway is simple: tactile AI is a productivity feature. Less breakage, fewer resets, fewer exception-handling events.

What’s next: stronger grips, more sensors, better materials—and better models

The direct answer: the roadmap is higher grip force capacity, richer sensing, and improved durability—paired with better learning systems.

The Johns Hopkins team plans to explore stronger grips, more sensors, and higher-quality materials. Those are the right next steps, but the bigger opportunity is how AI models evolve:

Three AI improvements that will matter most

- Self-calibration: hands that automatically compensate for sensor drift and material aging

- Personalized feedback mapping: learning what patterns a specific user interprets fastest

- Data-efficient learning: robust tactile inference without needing massive per-user datasets

A prosthetic that needs constant recalibration will frustrate users. A prosthetic that adapts quietly in the background becomes something people rely on.

A useful rule for AI prosthetics: if the user thinks about the system all day, the system isn’t doing its job.

Next steps if you’re building or buying AI-enabled robotics

The direct answer: start with tactile goals and safety metrics, then pick sensors and models that hit them.

If you’re an R&D lead, product manager, or innovation director, here’s a practical checklist:

- Define “safe grip” quantitatively (damage threshold, slip threshold, max allowable squeeze for common items)

- Choose tactile sensing that matches your object set (pressure distribution beats single-point force for varied items)

- Prototype closed-loop grasping early (don’t wait until the end to integrate sensing)

- Measure cognitive load (time eyes-on-object, user confidence scores)

- Plan for durability and hygiene (soft materials are great until they tear or absorb contaminants)

For organizations exploring AI in robotics & automation, this prosthetic hand is a strong reminder: the highest ROI intelligence often lives in the last centimeter—right where fingers meet the world.

A question worth sitting with as you plan your next project: Where in your robot’s workflow is uncertainty causing humans to compensate—and what would it take for the robot to feel trustworthy instead?