Multimodal robots that walk, fly, and drive are reshaping automation. Learn the AI stack, real use cases, and how to evaluate readiness.

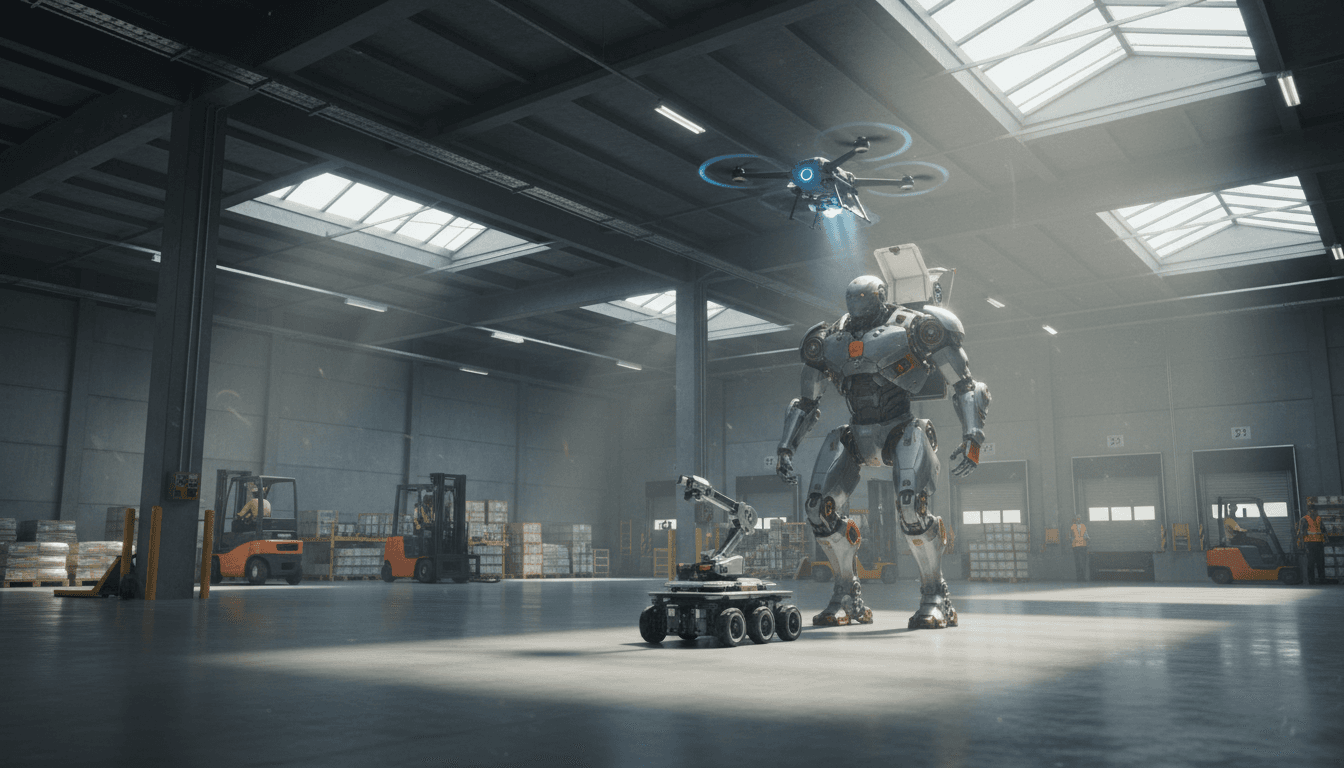

AI Multimodal Robots: Walk, Fly, Drive in One Workflow

Robotics is hitting an uncomfortable truth: most “autonomous” robots are only autonomous in the exact environment they were trained and tested in. The moment a workflow crosses a curb, a stairwell, a narrow aisle, a slippery ramp, or a crowded loading dock, the robot either stops—or you add a second robot, a teleoperator, or a human escort.

That’s why the recent wave of multimodal robotics demos matters. When a system can walk, fly, and drive (or at least combine locomotion modes across a team), it’s not a party trick. It’s a preview of what practical automation looks like in messy facilities where “edge cases” happen every hour.

In this edition of our AI in Robotics & Automation series, I’ll break down what multimodal robots signal for industrial automation, what AI capabilities make them possible, and how to evaluate whether they’re ready for your manufacturing, logistics, or service operation.

Multimodal robots are a response to a real operations problem

Answer first: Multimodal robots exist because real facilities are full of terrain transitions, and single-mode robots don’t handle transitions reliably enough without human help.

If you run a warehouse, plant, campus, or distribution hub, you already know the failure modes:

- AMRs are great on flat floors—until they hit door thresholds, elevators, or temporary obstructions.

- Drones are great for quick inspection—until they need endurance, payload, or precision interaction.

- Legged robots can traverse complex terrain—until the job becomes long-distance transport, where wheels win.

The demo highlighted in the RSS content—Caltech CAST and the Technology Innovation Institute showing a multirobot response team where a drone launches from a humanoid platform and then switches to driving mode—gets attention because it’s basically a condensed version of a real workflow:

- Reach the area (mobility)

- Get eyes on the situation (perception)

- Move through constraints (terrain transitions)

- Do something useful (manipulation or delivery)

That chain is what most automation programs struggle with. Not the first step. The whole chain.

Why this is showing up now (and not five years ago)

Three things are converging:

- Better onboard compute and more efficient models (so perception and planning can run closer to real time)

- Improved learning methods for contact-rich control (reinforcement learning and hybrid approaches)

- Systems engineering maturity (teams building robust state machines, safety layers, and fallback behaviors)

Multimodal robotics is less about one heroic robot and more about systems that can keep going when conditions change.

The AI stack behind “walk, fly, drive” isn’t one model

Answer first: The capabilities people describe as “AI robotics” are typically a stack: perception, state estimation, planning, and control—often trained and validated differently.

A common mistake I see in automation planning is assuming there’s one magic model that makes a robot intelligent. In reality, multimodal systems are assembled from components that each solve a different problem.

Perception: seeing is still the tax you always pay

Perception has to work across lighting changes, motion blur, reflective surfaces, and clutter. In the RSS examples, you can even see how teams simplify perception during research (for example, using motion capture) because reliable perception remains one of the hardest parts of real deployment.

In production, that means you should ask:

- What sensors does the robot rely on (RGB, depth, LiDAR, tactile)?

- What happens when sensors degrade (dust, glare, occlusion)?

- Is there a confidence-aware behavior (slow down, replan, stop)?

Planning: choosing actions under constraints

Multimodal systems need planning at multiple levels:

- Task planning: “Inspect that asset, then deliver this item.”

- Navigation planning: “Get to the asset through this facility.”

- Mode planning: “Switch from walking to driving to flying at the right time.”

That “mode planning” piece is where multimodal becomes real. If switching modes requires a human to intervene, it’s still a demo.

Control: the unglamorous part that makes or breaks deployments

The RSS roundup included a standout example: dynamic whole-body manipulation on a quadruped with a heavy object (a 15 kg tire). The interesting point isn’t just strength—it’s the coordination of contacts across arm, legs, and body.

This style of control is increasingly built using hybrid approaches:

- reinforcement learning to learn effective behaviors

- sampling-based control to maintain stability and handle constraints

- safety layers to keep actions within physical limits

The practical takeaway: when a vendor says “it’s fully autonomous,” ask what percentage of autonomy was achieved without external infrastructure, controlled environments, or special markers.

Where multimodal robotics actually fits in manufacturing and logistics

Answer first: Multimodal robots are most valuable where a workflow crosses environments—between indoor/outdoor, floor/stairs, aisle/yard, or inspection/manipulation.

Here are three high-ROI categories where multimodal capability (within one robot or across a coordinated team) can reduce human handoffs.

1) Yard-to-dock exception handling

Most distribution automation is strong inside the building. The weak link is the “gray zone”:

- trailer yard

- dock doors

- staging areas

- outdoor pallets and return assets

A coordinated system where one platform traverses rough areas while another performs close-range delivery or scanning can cut delays. It also reduces the need for staff to “go find the problem” during peak periods.

2) Inventory + inspection that becomes intervention

Drones can do fast scanning. Ground robots can carry heavier sensor payloads. Legged robots can reach places that were never designed for robots.

Multimodal systems shine when inspection turns into action:

- identify a leak → place a temporary containment device

- detect a missing label → apply a new one

- find a damaged package → move it to an exception area

This is where manipulation becomes the multiplier. It’s also where you need to be strict about safety and validation.

3) Service robotics in mixed public spaces

The RSS content included a humanoid platform demo and commentary that (rightly) raises concerns about robots near kids, pets, and fragile environments.

My stance: humanoids aren’t the default answer for public spaces yet. But multimodal thinking still applies—because public environments require graceful degradation:

- slow down near crowds

- switch to a safer mode

- hand over to a stationary kiosk

- request human assistance with clear context

In service settings, the “AI” that wins isn’t the flashiest. It’s the AI that reliably chooses the conservative action when uncertainty spikes.

How to evaluate multimodal robot readiness (without getting dazzled)

Answer first: The fastest way to cut through multimodal hype is to evaluate transitions, supervision needs, and recovery behaviors—not just best-case performance.

Here’s a practical checklist you can use in vendor calls, pilots, and RFPs.

Transition tests (the real multimodal bar)

Ask for performance evidence on:

- mode switching time (seconds, not vibes)

- stability during mode switching

- success rate across repeated trials

- what the robot does when switching fails

If the demo is edited, ask for uncut run logs.

Autonomy boundaries and human workload

Get explicit answers to:

- How often does teleoperation happen (per hour / per mission)?

- Who monitors the robot (one operator per robot or per fleet)?

- What’s the mean time to recover from a stop?

The uncomfortable reality: many “autonomous” deployments work because a human silently catches failure cases. That may still be a good business decision—but you need it priced in.

Perception and compute dependencies

Several research systems use external compute or external sensing to prove a point. In industrial settings, you should clarify:

- onboard vs offboard compute requirements

- network failure behavior

- degraded perception modes

A robot that becomes unsafe when Wi‑Fi drops is not an automation asset.

Safety: don’t accept marketing language

If a platform is marketed as home-safe or workplace-safe, ask for:

- safety-rated stop functions

- speed/force limiting approach

- collision detection strategy

- validation process in dynamic environments

Safety is not a brochure feature. It’s an engineering and compliance program.

What happens next: multimodal becomes the new “normal” for automation

Answer first: Over the next 12–24 months, expect multimodal robotics to shift from “one robot that does everything” toward teams of specialized robots coordinated by AI.

A single humanoid doing all tasks is a seductive idea, but it’s not the most economical path for most operations. What scales faster is:

- one platform optimized for robust mobility

- another optimized for sensing and inspection

- another optimized for manipulation

- shared task planning and fleet orchestration

This is also where AI in robotics & automation becomes a business tool. The value is not that a robot can do a backflip. The value is that your workflow stops needing humans as the glue between automation islands.

If you’re planning 2026 automation budgets right now (and many teams are), this is the right moment to map your facility’s “transition points”—the places where your current automation breaks down—and evaluate whether multimodal robots, coordinated fleets, or hybrid systems can reduce exceptions.

A useful rule: if a workflow requires a human mainly to handle transitions, you don’t have an automation problem—you have a multimodal mobility problem.

Want to pressure-test your use case? Take one critical process (returns handling, dock exceptions, line-side replenishment, or inspection rounds) and list every environment change it crosses. That list is your roadmap for multimodal robotics.

Next step: design a pilot that proves value, not just motion

You don’t need a moonshot pilot. You need a pilot that measures:

- exceptions avoided per week

- human touches eliminated per shift

- recovery time after failure

- throughput impact during peak periods

That’s the difference between an impressive video and a deployment that generates leads, budget, and executive support.

Multimodal robots—walking, flying, driving, and manipulating—are showing what the next generation of automation looks like: capable in the transitions, not just the straightaways. What part of your operation still falls apart at the transition points?