Adaptive grippers inspired by lobster tails show how AI and biomimicry can boost picking reliability in manufacturing and logistics. Learn what to pilot next.

AI Grippers Inspired by Lobster Tails for Automation

Factories don’t usually lose automation ROI because their robot arms are weak. They lose it because the last 30 centimeters—the gripper—can’t cope with reality.

Reality is slippery packaging, inconsistent parts, dusty bins, and items that bend, bruise, snag, or arrive slightly misaligned. Most companies respond by over-engineering fixtures, adding guarding, and narrowing the range of parts a cell can touch. It works… until a new SKU shows up in January and the whole “automated” line needs a week of retooling.

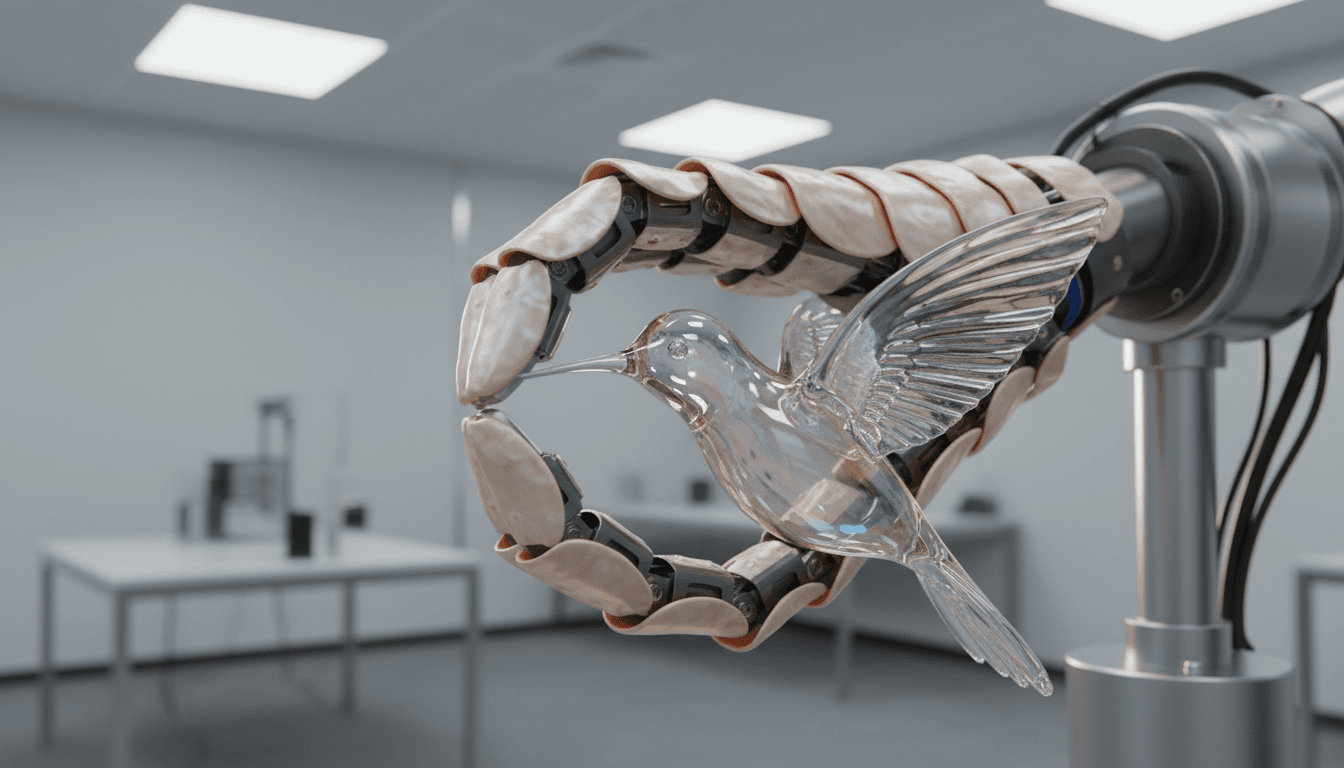

That’s why a small piece of robotics news—researchers integrating discarded crustacean shells (lobster-tail-like exoskeleton segments) into robotic grippers—matters far beyond a cool demo video. It points to a better direction for the AI in Robotics & Automation playbook: smarter, more adaptive end-effectors that use both materials and AI to handle variation instead of fighting it.

Why the gripper is still the bottleneck in AI-driven automation

A robot arm is basically a positioning machine. The gripper is where uncertainty piles up.

Even with strong perception and planning, real production lines still struggle at the moment of contact:

- Pose uncertainty: Vision gets you close, but glare, occlusions, or stacked items create millimeter errors.

- Compliance needs: Rigid fingers don’t tolerate misalignment; soft fingers can be too “squishy” and imprecise.

- Surface and fragility variance: One day you’re grabbing shrink-wrapped cartons, the next it’s bare plastic, foam, or produce.

- Cycle-time pressure: The gripper can’t spend 5 seconds “feeling around” if the takt time is 2 seconds.

Here’s the stance I’ll defend: Most automation programs over-invest in robot selection and under-invest in end-effector strategy. That’s backwards. If you want flexible automation, grippers and sensing are where flexibility is won.

What lobster tail mechanics teach us about “good” robotic fingers

A lobster tail (or more precisely, the segmented abdomen exoskeleton of crustaceans like langoustines) is an elegant mechanical compromise:

- Segmented rigidity: It’s not floppy like silicone, but it’s not a single stiff plate either.

- Directional compliance: It bends predictably in certain directions.

- Strength-to-weight efficiency: Nature is stingy with mass; exoskeleton structures are lightweight but tough.

- Built-in geometry: The surface texture and curvature contribute to grip and stability.

When researchers repurpose these shell structures into a gripper, the headline isn’t “robots made of lobster parts.” The headline is:

Mechanical intelligence can reduce the burden on AI control.

If the finger naturally conforms to a range of shapes, your perception and force-control stack doesn’t need to be perfect to avoid slips, crushes, or mis-grasps.

Bio-inspired doesn’t mean “soft robotics only”

A common misconception is that biomimicry equals soft robots. Not true.

Bio-inspired design often lives in the middle ground:

- Semi-rigid structures

- Compliant joints

- Anisotropic stiffness (stiff one way, flexible another)

- Surface micro-textures that increase friction

That middle ground is where industrial automation gets real value: predictable behavior at high cycle rates.

Where AI actually fits: perception, grasp selection, and force control

The lobster-tail-style structure is a great story, but it becomes a business story when paired with AI.

In modern robotic manipulation, AI typically earns its keep in three places:

1) Vision AI for “good-enough” localization under messy conditions

Industrial lines still face reflective packaging, variable lighting, and partial occlusion. Vision models—especially modern multi-view and multimodal approaches—help estimate:

- Object pose hypotheses (not just one guess)

- Surface normals / grasp affordances

- Confidence and uncertainty

The best cells I’ve seen don’t pretend vision is perfect. They design the workflow so vision gets the robot near the object, and the gripper’s compliance plus sensing finishes the job.

2) Learning-based grasp selection (affordances over exact geometry)

Rigid, CAD-driven grasping is brittle. It assumes:

- Known geometry

- Known placement

- Known friction

Learning-based grasping flips the idea: it looks for affordances—places that are likely to work—then tests and adapts.

A bio-inspired gripper helps because it increases the number of “likely to work” contact situations. That means:

- Fewer failed picks

- Less need for perfect part presentation

- Lower dependence on custom fixtures

3) Force/torque + tactile feedback for slip detection and gentle handling

If you care about damage rates and rework, you need feedback at the contact level.

AI models can fuse signals from:

- Force/torque sensors at the wrist

- Motor currents

- Tactile arrays (when available)

- Micro-vibration signatures (slip often has a tell)

Then you can run strategies like:

- Increase normal force only when slip risk rises

- Regrasp quickly without stopping the line

- Adjust approach angle on the next cycle

This is how you turn a “cool gripper” into operational reliability.

Practical applications: where adaptive grippers pay back fastest

If you’re choosing where to pilot AI-driven robotics with adaptive grippers, target tasks where variation is unavoidable and labor is hardest to staff—especially in late Q4 and early Q1 when seasonal volume and SKU churn spike.

Manufacturing: kitting, machine tending, and mixed-part handling

Adaptive grippers reduce the need for part-specific nests in:

- Kitting for assembly lines (especially high-mix)

- Machine tending where blanks vary slightly

- Secondary operations like labeling, packing, and inspection handoffs

The win isn’t “the robot can pick anything.” The win is: the robot can keep picking when reality deviates from the spreadsheet.

Logistics: piece picking and returns processing

Warehouses live in the long tail:

- Bags, boxes, tubes, clamshells, poly-mailers

- Damaged packaging

- Unknown orientation

A gripper that can passively conform, paired with AI that chooses stable grasps, is one of the few approaches that scales beyond “demo aisle” conditions.

Food and consumer goods: gentle handling without slowing down

If you’ve ever tried to automate handling for:

- Produce

- Baked goods

- Fragile blister packs

…you’ve felt the trade-off between softness (gentle) and precision (fast, repeatable). Semi-rigid bio-inspired structures can hit a more practical middle.

What most teams miss: the design rules for AI + adaptive grippers

Buying a fancy gripper and adding a model isn’t a strategy. The teams that succeed follow a few design rules.

Design rule 1: Let mechanics absorb variability before software does

If a finger shape naturally guides alignment, you get robustness “for free.” In production, free robustness is priceless.

Design rule 2: Measure outcomes that operators care about

Track metrics that map to downtime and quality:

- Pick success rate (per SKU, per shift)

- Mean recovery time from a failed grasp

- Damage rate / scrap attributed to handling

- Unplanned stoppages per 10,000 picks

If you can’t measure it, you can’t prove the cell improved.

Design rule 3: Treat grasping as a closed-loop system

A static grasp plan is a fragile plan.

Closed-loop grasping means your system can:

- Approach

- Make contact

- Sense slip / misalignment

- Correct in milliseconds

This is exactly where AI helps: it classifies states and selects micro-actions quickly.

Design rule 4: Plan for “unknown unknowns” with operational guardrails

Add guardrails so adaptation doesn’t become chaos:

- Allowed force envelopes by product class

- Timeouts and safe abort poses

- Automatic bin re-scan triggers

- Clear operator recovery steps that take < 60 seconds

In December peak operations, the best automation is the one that’s recoverable by normal staff, not a PhD on call.

“Bio-hybrid” robotics and sustainability: nice bonus, not the main point

Turning discarded shell waste into functional robotic components is a compelling sustainability story, especially as manufacturers face pressure to reduce material waste and improve circularity.

But I wouldn’t pitch this internally as a “green gripper project” first.

Pitch it as:

- Higher tolerance to variation

- Lower changeover effort

- Fewer fixtures and less line babysitting

If you get sustainability benefits on top—great. Just don’t let the narrative distract from the operational thesis.

What to do next if you’re evaluating AI grippers for your operation

If you’re trying to turn adaptive, AI-enabled manipulation into leads and real deployments (not another pilot that dies in procurement), focus on a fast, controlled path.

- Pick a single workflow with high variation (returns, kitting, mixed-SKU packing).

- Define success with three numbers: pick success rate, damage rate, and recovery time.

- Run a two-gripper bake-off: one conventional, one adaptive/compliant. Keep the rest of the cell identical.

- Instrument everything (force, currents, vision confidence) so failures become training data.

- Design operator recovery before you design dashboards.

The goal isn’t a robot that never fails. The goal is a robot that fails gracefully and recovers fast.

Where this fits in the AI in Robotics & Automation series

This lobster-tail-inspired gripper is a reminder that AI in robotics isn’t only about bigger models. It’s about building complete systems where:

- materials and mechanics reduce uncertainty,

- sensors detect what matters,

- and AI chooses actions that keep the line moving.

If your automation roadmap for 2026 includes more SKUs, more customization, and tighter labor markets, the “future of robotic hands” won’t look like rigid metal claws. It’ll look like adaptive grippers inspired by nature and guided by AI—because that’s what the job demands.

If you’re planning a pilot in the next quarter, which part of your operation is most constrained by grasping failures: the vision step, the end-effector design, or the recovery workflow?