Jet-powered humanoids like iRonCub3 show why AI-driven mobility matters. See what flying robots teach us about autonomy, safety, and real-world automation.

AI-Powered Flying Humanoids: Beyond the iRonCub Hype

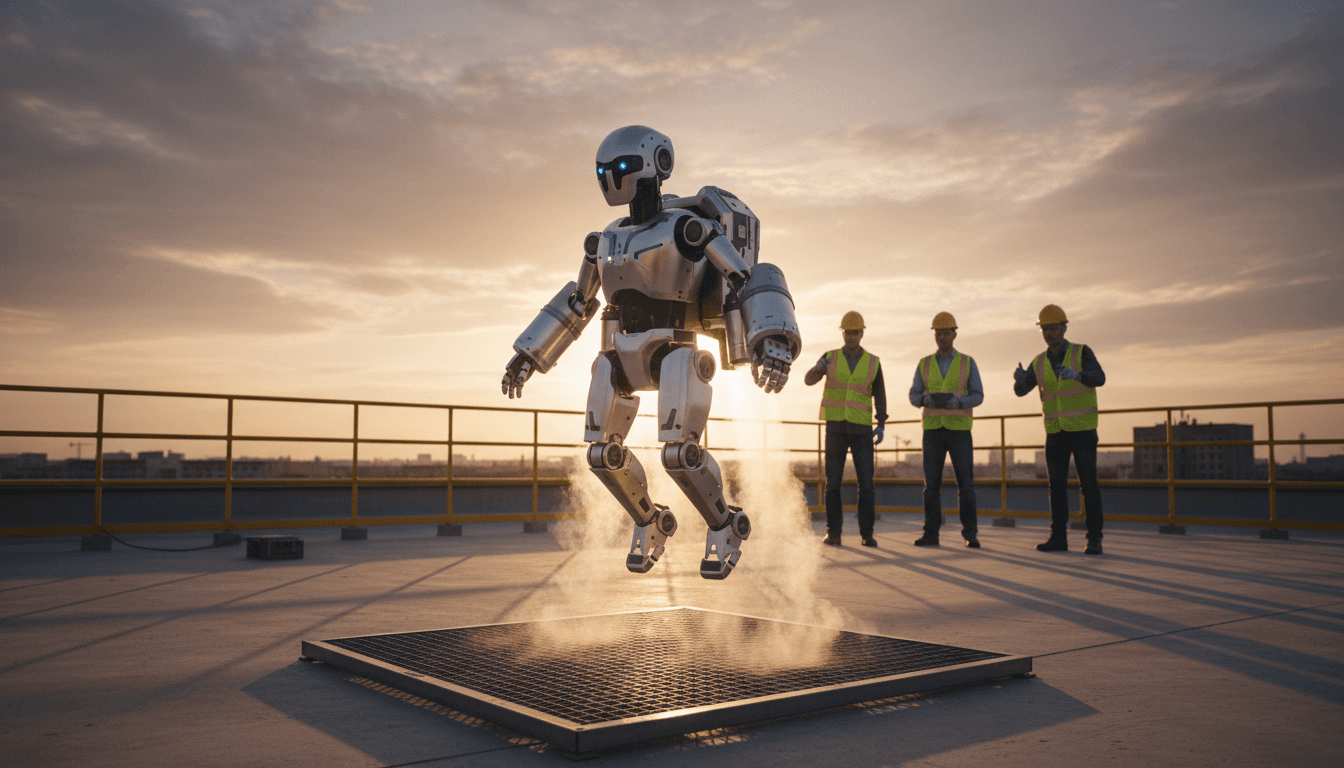

A jet-powered humanoid robot recently lifted off and held a stable hover—about 50 centimeters for several seconds—using four jet engines that together generate over 1,000 newtons of thrust. That’s not a flashy lab demo; it’s a signal that “mobility” in robotics is changing shape.

The robot is iRonCub3, built on the iCub platform (a child-sized humanoid originally created for research in embodied intelligence). It still has the unmistakable “robot baby” face—which is exactly why people share the videos. But the serious part isn’t the aesthetic. The serious part is what it forces robotics teams to solve: AI-driven control under brutal physics constraints—slow engine spool dynamics, aerodynamic disturbances, and exhaust that’s around 800 °C and nearly supersonic.

This matters to anyone building automation for disaster response, inspection, logistics, and industrial service. Most companies get stuck choosing between ground robots that can manipulate objects but can’t traverse rubble, and drones that can traverse anything but can’t do much once they arrive. A flying humanoid is the uncomfortable third option that tries to combine both—and it’s pushing the entire field forward.

Why a flying humanoid is more than a stunt

A flying humanoid isn’t “a drone with arms.” It’s a fundamentally different robotics problem where the body itself becomes a control surface.

iRonCub3’s configuration puts turbines on the back and arms, and control comes not just from changing thrust, but from moving the arm-mounted engines to maintain stability. That’s the first big reason the project matters: it forces a new generation of whole-body flight control—the same type of thinking that will increasingly show up in robots that operate near people, inside facilities, and outdoors in messy wind.

The real goal: get there fast, then work efficiently

The most defensible use case is disaster response:

- Fly over obstacles during floods, fires, collapses, or industrial incidents

- Land and walk to conserve energy

- Use hands and arms to open doors, move debris, turn valves, and carry supplies

That hybrid idea—high-speed approach + energy-efficient ground work—is the core automation story. If you’ve deployed robots in real environments, you already know the pain: the last 30 meters is always the hardest. The world is full of stairs, blocked hallways, broken flooring, doors that swing the wrong way, and debris that “just wasn’t in the map.”

A flying humanoid won’t make environments less chaotic. It makes the robot less dependent on them being tidy.

The AI and control stack you actually need for humanoid flight

Stable flight isn’t a single algorithm; it’s a systems engineering problem. The reason iRonCub3 is a big deal in the “AI in Robotics & Automation” series is that it highlights a trend we’re seeing across automation in 2025: AI isn’t replacing classical control—it’s filling the gaps where modeling breaks.

1) Aerodynamics isn’t optional anymore

Most humanoid robotics stacks historically focused on:

- rigid-body dynamics

- contact forces

- actuator limits

- balance and footstep planning

Once you add jet propulsion, aerodynamics becomes first-class:

- the robot experiences changing lift/drag profiles as limbs move

- exhaust interacts with the robot’s own body

- downwash and reflected flow matter near the ground and near walls

A practical takeaway: if you’re building robots meant for outdoor work (yards, ports, construction sites), you should expect wind compensation to become a standard humanoid capability—even when the robot never leaves the ground.

2) “Thrust estimation” is a transferable capability

One underappreciated point: algorithms developed to estimate and control thrust have immediate spillover value. Directed thrust shows up in:

- eVTOL platforms

- ducted-fan drones near obstacles

- industrial blowers and pneumatic tools

- stabilization systems for mobile manipulation on moving bases

In other words: even if flying humanoids never become common products, the AI estimation and control tools are already useful.

3) Slow actuators force smarter prediction

Jet engines don’t respond instantly; they spool up and down with delay. That pushes the control architecture toward:

- model predictive control (MPC) to anticipate state changes

- learning-based disturbance models to handle unmodeled aero effects

- state estimation that remains stable under vibration and turbulence

If you’re buying robotics for industrial automation, this is a good litmus test for vendors: ask how their autonomy behaves when actuators have latency, sensors are noisy, and the environment fights back. A team that understands prediction and robustness will ship better systems—even for “boring” ground robots.

A simple stance: autonomy that only works in fast, clean loops won’t survive outside demos.

What flying humanoids could do for logistics and industrial service

Disaster response is the easiest story to tell, but it’s not the only one. The combination of advanced mobility + manipulation has direct implications for industries that care about uptime and access.

Facilities inspection where access is the bottleneck

Think of large industrial sites—power plants, refineries, shipyards, tunnels, and high-bay warehouses. Inspection is often constrained by:

- scaffolding and lift equipment scheduling

- confined spaces

- access restrictions during operations

A flying humanoid concept suggests a future robot that can:

- approach quickly (air)

- land safely in a constrained area

- perform close-in tasks (ground) like turning a latch, repositioning a sensor, or placing a temporary camera

Even before humanoids fly, the intermediate product category is likely: aerial robots with limited manipulation for “touch tasks” (pressing buttons, placing tags, pulling lightweight handles).

High-consequence service work: valves, breakers, and doors

There’s a class of work that sounds trivial until you automate it: opening a door, turning a valve, flipping a breaker. These are the interfaces of the physical world.

Humanoids are compelling here because they match the environment humans built. Adding flight changes the access problem. But it also raises a hard operational question: How do you make this safe around people and equipment?

Which leads to the part many teams underestimate.

The uncomfortable constraints: heat, safety, testing, and operations

A jet-powered humanoid brings constraints that most robotics companies aren’t culturally prepared for.

Heat and exhaust change the safety envelope

Exhaust at 800 °C isn’t a minor integration issue. It affects:

- material selection and thermal shielding

- safe standoff distances

- indoor viability (often a non-starter)

- operational procedures near responders, victims, and flammable materials

That’s why, in my view, the most realistic near-term value of projects like iRonCub3 is the autonomy and modeling breakthroughs, not immediate deployment of turbine-humanoids into city streets.

Testing becomes an operations program

When robots start flying with high-energy systems, progress depends on:

- test stands and containment rigs

- aviation coordination and airspace rules

- repeatable flight test plans

- incident response plans (for the robot itself)

This is where advanced robotics starts to look like aerospace. Teams that ignore that reality lose years.

“People also ask” (and the answers you can use internally)

Can a flying humanoid replace drones?

No. Drones win on simplicity and efficiency for pure sensing. Flying humanoids are for tasks where manipulation after arrival justifies the complexity.

Why not use a ground humanoid plus a drone?

That’s a valid architecture and will stay common. The flying-humanoid bet is about reducing handoffs, planning, and operator load in chaotic environments where coordinating multiple robots is harder than it sounds.

Is AI the main blocker?

AI is a blocker, but not the only one. The hardest blockers are energy density, thermal management, safety certification paths, and reliable autonomy under aero disturbances.

What automation leaders should take from iRonCub3 in 2026 planning

If you run robotics programs in logistics, manufacturing, or critical infrastructure, here are the practical lessons worth keeping:

- Mobility is becoming multi-modal. Expect robots that walk, roll, climb, and eventually hop or short-flight—chosen by task economics.

- AI + classical control is the winning combo. Pure end-to-end learning won’t be trusted for high-energy systems; hybrid stacks will.

- Force/thrust estimation is a competitive advantage. The teams that can infer forces reliably from messy sensors will outperform on real jobs.

- Testing infrastructure is product strategy. If a platform can’t be tested frequently and safely, it won’t iterate fast enough to win.

Where flying humanoids fit in the bigger “AI in Robotics & Automation” story

The broader theme of this series is that AI is pushing robots from scripted motion to adaptive behavior in uncontrolled environments. Flying humanoids are an extreme version of that shift: the robot has to reason about dynamics, airflow, thermal limits, and mission objectives—often with partial information.

And even if you never buy a jet-powered humanoid, you’ll benefit from the techniques it forces into existence: robust autonomy, aerodynamic compensation, predictive control under latency, and transferable force-estimation tools.

If you’re exploring AI-driven mobility for your operations—whether that’s inspection robots, warehouse automation, or emergency-response systems—start with a simple internal question: Which of your workflows fail because the robot can’t reach the worksite, and which fail because it can’t manipulate once it gets there? The winners in 2026 will be the teams that stop treating those as separate problems.