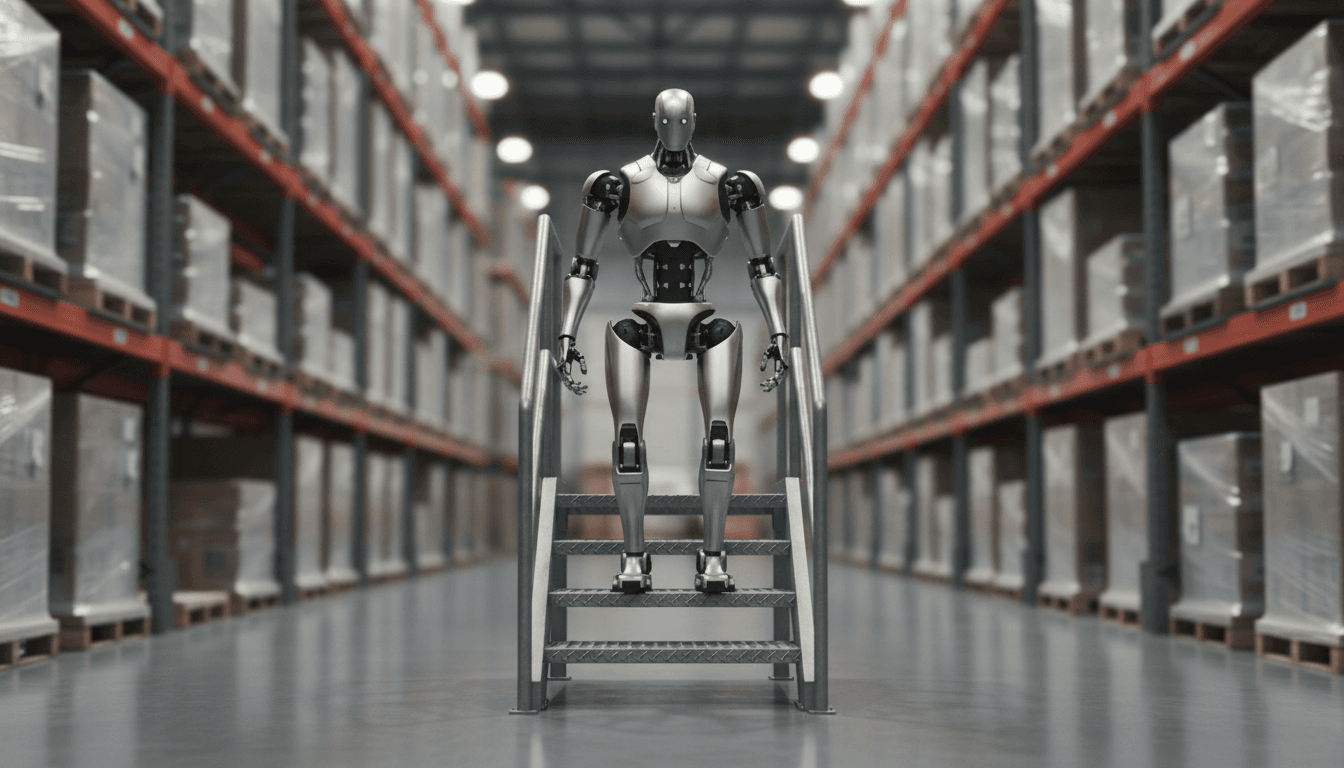

AI-powered biped robots are getting closer to real warehouse work. Here’s what stair climbing and modern control stacks reveal about readiness.

AI-Powered Biped Robots: From Lab Walks to Warehouses

A biped robot doesn’t fail because it “can’t walk.” It fails because the world won’t cooperate.

A factory floor has slick patches. A logistics aisle has cable covers. A stair has a slightly nonstandard rise. And the moment conditions shift, two-legged robots face a brutal requirement: they must keep their balance while making and executing decisions in milliseconds.

That’s why the conversation in Robot Talk Episode 137 with Oluwami “Wami” Dosunmu-Ogunbi (Ohio Northern University) hits at the right moment for anyone building automation roadmaps for 2026. The biped story isn’t just about flashy demos. It’s about controls, learning, and education pipelines—the stuff that determines whether humanoids become dependable workers in manufacturing and logistics or remain expensive science projects.

Two-legged robots are a controls problem first

Bipedal locomotion is fundamentally about stability under uncertainty. The robot has to put a foot down, transfer weight, and commit—without perfect information about friction, compliance, or tiny height differences.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: Most teams over-focus on the “body” (hardware) and under-invest in the “brainstem” (control stack). You can buy better actuators and stronger joints, but if your control strategy can’t recover from real-world variability, you’re stuck babying the robot in curated environments.

Wami’s work sits right in that practical reality: controls for bipedal locomotion—including capabilities like walking and stair climbing. Stair climbing matters because it’s a proxy for everything annoying in real facilities: discontinuities, changing contact geometry, and the need for precise foot placement.

What makes biped control hard (in plain terms)

Two-legged robots aren’t hard because they’re complicated. They’re hard because they’re underactuated and contact-driven.

- Underactuated dynamics: During phases of walking, not every degree of freedom is independently controllable.

- Hybrid dynamics: The system switches between continuous motion (swinging a leg) and discrete events (foot impact).

- Contact uncertainty: The “ground” might be rubber matting, painted concrete, a steel grate, or a stair edge.

A useful way to say it: biped robots don’t just move through space—they negotiate with the ground.

Where AI actually helps (and where it doesn’t)

AI is becoming central to biped robotics, but not in the simplistic “throw a neural net at it” way. The strongest results in the field come from pairing model-based control with learning-based adaptation.

If you’re evaluating humanoids for industrial automation, it helps to separate AI’s value into three buckets.

1) Learning better “reflexes” for disturbance recovery

A warehouse-ready biped needs fast recovery when something goes wrong:

- a foot lands slightly off-target

- a payload shifts

- the surface is lower friction than expected

- the robot is bumped by a cart

Learning-based policies (often trained in simulation) can produce robust recovery behaviors that are hard to hand-design. But the win isn’t magic—it’s exposure to massive variation during training.

Snippet-worthy truth: The best locomotion AI doesn’t teach robots to walk. It teaches robots to not fall when walking gets weird.

2) Adapting gait parameters to real-world variability

Even classic approaches (like trajectory optimization and model predictive control) benefit from AI when you need to tune or adapt:

- step length and cadence

- foot placement under constraints

- compliance and impedance settings

- energy usage vs. speed trade-offs

This matters in manufacturing and logistics because you rarely want “maximum speed.” You want consistent throughput without incidents.

3) Perception-to-contact: picking safe footholds

Perception is often the missing link in biped demos. In real facilities, the robot has to decide where to step based on partial, noisy sensing.

Modern embodied AI pipelines increasingly fuse:

- depth sensing and semantic segmentation (what surfaces are walkable?)

- uncertainty estimates (how confident is the robot?)

- terrain classification (grate, carpet, wet floor)

Then controls has to execute those decisions safely.

Where AI doesn’t save you

AI won’t fix:

- poor mechanical design margins

- insufficient sensing at the foot/ankle

- weak safety engineering

- lack of fall management and stop behaviors

If you’re buying or building two-legged robots for automation, ask for the unsexy proof: slip recovery tests, pushes, repeated stair cycles, and failure-rate reporting.

Stair climbing is the benchmark your facility cares about

Stairs sound like a “service robot” problem. In practice, stair performance is a great stress test for industrial humanoids because it forces capabilities that show up everywhere else.

Why stairs are the litmus test

Stairs require:

- precise foot placement (small errors compound quickly)

- vertical work (torque and power demands spike)

- robust contact transitions (toe/heel interactions vary)

- tight stability margins (the center of mass has less forgiveness)

If a robot can climb stairs reliably, you’re closer to trusting it on:

- dock plates and thresholds

- ramps between floor levels

- uneven warehouse mezzanines

- floor transitions (concrete → matting → epoxy)

Operational takeaway: Stair climbing isn’t a feature. It’s an indicator of whether the locomotion stack can handle discontinuities.

The “Biped Bootcamp” idea is how the talent gap gets fixed

The part of Episode 137 I wish more automation leaders would pay attention to isn’t only the lab research—it’s the education pipeline.

Wami developed a Biped Bootcamp technical document during her PhD and is transforming it into an undergraduate curriculum. That matters because biped robotics has a knowledge bottleneck: too few engineers are fluent across the full stack.

What biped teams actually need (and struggle to hire)

A strong biped engineer doesn’t just know one thing. They can move between:

- rigid-body dynamics

- estimation and sensor fusion

- feedback control and stability concepts

- optimization (trajectory generation)

- learning systems (policy training, sim-to-real)

- real-time software and safety constraints

Most companies hire specialists and then wonder why integration drags.

My take: If your humanoid program is slipping timelines, it’s probably not because your team is “missing one more model.” It’s because you’re missing people who can connect models to hardware under real-time constraints.

Education programs that teach biped robotics earlier—at the undergraduate level—reduce ramp time and make the field less dependent on a handful of overbooked experts.

What this means for manufacturing and logistics in 2026

Two-legged robots are still early in many industrial deployments, but the direction is clear: the value proposition is adaptability.

Wheels dominate when the world is structured. Legs start to win when the environment is semi-structured and changing—especially where you’d otherwise redesign the facility or add conveyors, lifts, or ramps.

Near-term use cases that are realistic

If you’re planning pilots, the most credible applications share two traits: limited scope and clear fallback modes.

- Material handling in mixed environments: moving totes between zones with occasional thresholds or ramps

- Mobile manipulation support: carrying items while using hands for doors, latches, or stabilizing tasks

- Inventory and inspection in tight spaces: areas built for humans, not AMRs

- Mezzanine and back-of-house movement: where adding infrastructure is expensive

Metrics that matter more than “can it walk?”

If you’re evaluating AI-powered humanoid robots for automation, push vendors (or your internal team) on measurable performance:

- Mean time between falls (MTBF): not just “it didn’t fall in the demo”

- Recovery success rate: slips, trips, and pushes under defined tests

- Cycle repeatability: can it do the same route 1,000 times without drift?

- Changeover time: how long to adapt to a new area or payload?

- Safety behaviors: safe stop, controlled descent, and human proximity handling

Snippet-worthy truth: A biped that walks 10 minutes is a demo. A biped that walks 10 hours is a product.

A practical roadmap: how to de-risk biped automation

If you’re a robotics leader or operations exec trying to decide whether two-legged robots belong in your 2026 plan, here’s what works.

Start with a “walking spec,” not a cool video

Define the environment and requirements in operational language:

- floor surfaces and contaminants (dust, water, oil)

- slopes, thresholds, ramps, and stairs

- payload ranges and how the load shifts

- speed requirements vs. safety zones

- allowable downtime and maintenance windows

Then demand testing against that spec.

Build a staged pilot that forces learning and integration

A staged deployment beats a big-bang rollout:

- Stage 1: Controlled route with known terrain and no human mixing

- Stage 2: Controlled route + variability (surface changes, payload changes)

- Stage 3: Human-shared environment with strict safety constraints

Each stage should have go/no-go criteria tied to the metrics above.

Invest in the “boring” stack: estimation, foot sensing, and safety

The robots that survive real facilities have:

- reliable state estimation under vibration

- foot contact sensing and fast detection of slip

- conservative safety layers that override learned behaviors

- logging and post-incident analysis tooling

This is also where AI helps: anomaly detection, predictive maintenance, and automatic identification of failure modes from logs.

Where the field is heading next

Expect 2026 to bring less hype about “general-purpose humanoids” and more focus on task-constrained humanoids: robots designed for a narrow set of warehouse and manufacturing workflows, with AI policies tuned to those workflows.

And education efforts like Wami’s Biped Bootcamp are a big part of why. The more engineers who understand locomotion end-to-end, the faster the industry shifts from one-off demos to repeatable deployments.

If you’re building an AI in Robotics & Automation strategy, biped robots belong on your radar—but they belong there with a grown-up mindset: measurable reliability, safety-first controls, and pilots designed to surface failure modes early.

What would change in your facility design if your robots could handle stairs, thresholds, and messy ground without special infrastructure—and you could prove that reliability with data rather than demos?