Asset-level climate risk is reshaping underwriting. See how AI scales extreme weather risk reviews across portfolios, suppliers, and insurance pricing.

Asset-Level Climate Risk: The AI Shift in Insurance

Swiss Re estimates 2025 global insured natural catastrophe losses hit $107 billion, with total economic losses at $220 billion. That’s not a scary “future trend.” It’s a budgeting problem right now—especially for anyone underwriting property, financing infrastructure, or running portfolios where a single flood or wildfire can erase a year of returns.

That’s why Apollo’s recent move matters. After running top-down climate risk analyses since 2023, Apollo says it’s expanding into bottom-up, asset-level reviews that look at how extreme weather changes valuations and cash-flow durability before a deal closes. If you work in insurance, risk, or operations, the headline isn’t “private markets care about climate.” The headline is: granular climate risk is becoming a standard input to pricing, underwriting, and capital decisions.

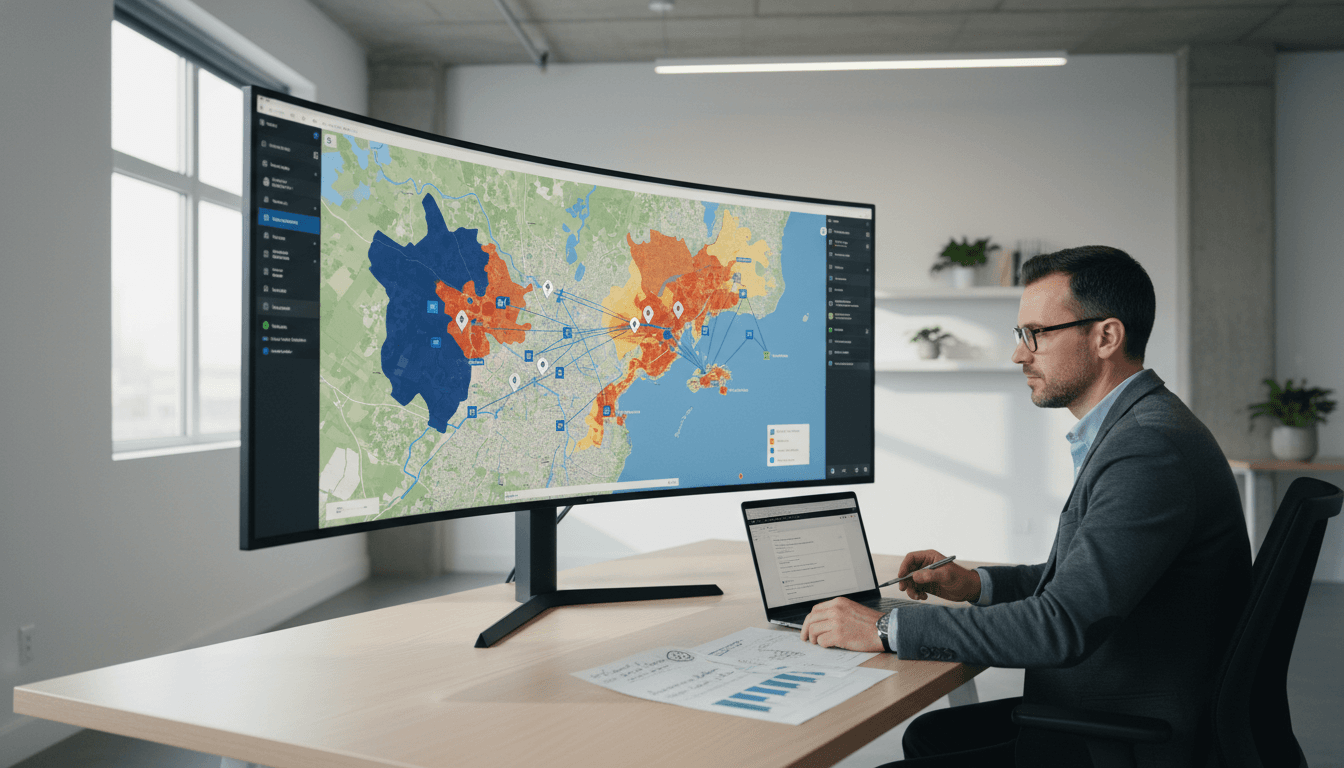

This post is part of our AI in Supply Chain & Procurement series, so I’ll take a clear stance: asset-level climate risk reviews won’t scale with spreadsheets and annual vendor reports. The only practical way to make them routine—across portfolios, supply chains, and insurance programs—is to operationalize them with data pipelines and AI models that turn weather and exposure signals into decisions.

Why asset-level climate risk is suddenly “day-one due diligence”

Asset-level climate risk is now day-one due diligence because losses are frequent enough to be priced into markets today, not treated as a long-horizon scenario.

Apollo’s sustainability leadership framed it plainly: climate-driven disruptions affect operating costs, supply chains, and insurance markets, which makes the financial impact immediate. That’s the part many teams miss. Extreme weather isn’t only about a damaged building. It’s about:

- Higher insurance premiums (or reduced availability)

- Collateral value swings (especially in mortgages and hard assets)

- Operational downtime (power, water, workforce access)

- Supplier failure and logistics delays (inventory, replacement parts, distribution)

If you’re underwriting commercial property, builders risk, inland marine, or even large casualty programs tied to operational continuity, this cascades fast.

Top-down vs. bottom-up: what changes in practice

Top-down climate risk typically asks: “How exposed is this portfolio or sector to hazards over time?” It’s useful for strategic allocation.

Bottom-up asset-level risk asks: “Is this facility, this loan, this supplier site likely to face drought, flood, heat, or wildfire that changes expected cash flow during the hold period?” That’s underwriting-grade.

Apollo cited examples like loan-level mapping in mortgage portfolios and evaluating exposures across drought, flood, heat, and wildfire in hard-asset sectors where hazards can influence collateral values and cash-flow durability.

For insurers, the implication is direct: as asset owners harden their underwriting and financing decisions, they’ll expect carriers to bring the same level of precision—especially during renewals, mid-term changes, and claims disputes.

What Apollo’s approach signals for insurers and MGAs

Apollo’s expansion is a market signal: investors are tightening how they validate valuation models in private markets, and they’re doing it by making climate risk measurable at the asset level.

Insurers and MGAs should read that as both threat and opportunity.

Threat: “good enough” CAT and exposure assumptions won’t hold

If a private credit team can map hazards to a loan or facility, buyers will ask why their insurance program still relies on:

- static, infrequently updated COPE data

- generic location risk tiers

- annual questionnaires that don’t match operational reality

The mismatch shows up in loss ratios and retention decisions. It also shows up as friction: longer quote cycles, more referrals, more “we need more info” loops.

Opportunity: AI enables underwriting that matches investor scrutiny

Here’s the better way to approach this: treat climate peril exposure like any other continuously updated risk signal (similar to credit risk monitoring or cyber posture scoring).

AI can support that shift by:

- automating data enrichment (geocoding, building attributes, occupancy)

- generating near-real-time hazard indicators (heat stress, flood likelihood, wildfire proximity)

- producing explanations that underwriters and insureds can act on (not just risk scores)

This isn’t about replacing catastrophe models; it’s about making risk assessment usable at scale for everyday underwriting and portfolio management.

Where AI fits: turning climate hazards into supply chain and underwriting decisions

AI fits best where the industry currently loses time: translation and scale. Translation from raw hazard data into operational and financial impact. Scale across thousands of locations, suppliers, and policies.

From “hazard” to “business interruption”: the missing link

Most companies can tell you a site is in a flood zone. Fewer can quantify what that means for:

- downtime probability during the next 12–36 months

- inventory spoilage and replacement lead times

- rerouting costs and carrier capacity constraints

- claims severity given local contractor scarcity

AI models can connect these dots by combining structured and unstructured inputs:

- hazard layers (flood depth, wildfire risk, heat days)

- asset characteristics (construction, elevation, critical equipment)

- operational telemetry (power consumption, cooling loads, maintenance logs)

- supply chain dependency graphs (single-source components, route constraints)

- insurance outcomes data (claims severity by peril and region)

When done well, the output isn’t “high risk.” It’s a decision-ready statement like:

A site’s flood exposure increases expected downtime by 18–25 days over a 24‑month horizon unless backup power and equipment elevation are improved.

That’s the sort of sentence that changes underwriting terms and procurement plans.

Data centers are the perfect example

Apollo called out data centers directly: power is often the largest operating expense, and water sourcing, use, and recycling can affect costs, regulatory exposure, and resilience.

In insurance terms, data centers concentrate multiple risk drivers:

- high-value equipment and tight tolerances (property severity)

- uptime requirements (business interruption severity)

- dependency on power and water utilities (contingent BI)

- supplier fragility (replacement parts and skilled labor)

AI can help underwriters and risk engineers evaluate these facilities faster by extracting information from engineering reports, monitoring sensor data, and flagging design choices that correlate with past losses.

For procurement teams inside data center operators, it’s the same idea: AI can map where you’re exposed to single points of failure—like one transformer supplier, one cooling vendor, or one water district.

A practical playbook: building asset-level risk reviews that actually scale

Asset-level climate risk reviews scale when you treat them as an operating system, not a one-off assessment.

Below is a practical approach I’ve seen work across insurance and risk teams that need speed and defensibility.

1) Start with decision points, not datasets

Define where the analysis must land:

- underwriting: eligibility, pricing, terms, deductibles

- portfolio: aggregation, reinsurance strategy, capital allocation

- claims: pre-event actions, response triage, severity controls

- procurement: supplier selection, dual-sourcing, inventory buffers

If you don’t anchor to decisions, teams collect data forever and still argue at the finish line.

2) Create an “asset identity” that underwriting can trust

Most climate modeling fails operationally because location data is messy.

Minimum viable asset identity:

- verified address + geocode confidence

- occupancy / use type

- construction class and year built (if property)

- critical equipment list (if industrial / data center)

- insured values with time stamps

AI helps here by reconciling naming variations, deduplicating locations, and extracting missing attributes from documents.

3) Blend acute and chronic hazards into one view

Apollo referenced acute and chronic climate hazards. Insurers should do the same.

- Acute = event-driven shocks (floods, storms, wildfire)

- Chronic = slow pressure on operations (heat stress, drought, sea-level creep)

Underwriting needs both because chronic stress often shows up as higher frequency losses, higher maintenance costs, and narrower insurance availability.

4) Add supply chain dependency mapping (this is where most programs are weak)

If this post fits anywhere in our AI in Supply Chain & Procurement series, it’s here: physical risk isn’t limited to owned assets.

Build a basic dependency graph:

- tier-1 and tier-2 suppliers by location

- logistics routes and hubs

- critical utilities and service providers (power, water, telecom)

Then ask two underwriting-grade questions:

- What’s the probable maximum operational disruption if one node fails?

- How quickly can operations shift to alternates, and what does that cost?

AI can accelerate this by classifying supplier categories, extracting locations from contracts, and continuously monitoring risk signals.

5) Operationalize outputs: alerts, not PDFs

If the only output is a quarterly report, you’ll miss the event.

Operational outputs that work:

- risk scoring with confidence intervals and explanations

- threshold-based alerts (e.g., “heat risk > X for 10 days”)

- underwriting rule suggestions (term adjustments) with audit trails

- pre-loss recommendations prioritized by ROI (elevation, defensible space, redundancy)

This is also where governance matters: models must be explainable enough to defend underwriting decisions and avoid unfair outcomes.

Common questions insurers ask (and direct answers)

Do asset-level climate reviews replace catastrophe models?

No. They complement CAT models by making the results actionable at the account, location, and supplier level—where underwriting and risk engineering decisions happen.

What’s the biggest blocker to doing this well?

Data quality and workflow adoption, not the hazard layer itself. If underwriters don’t trust location data or can’t get outputs in the systems they use daily, the program stalls.

How fast can a carrier or MGA get value from AI here?

If you already have decent exposure data, you can typically deliver value in 8–12 weeks by focusing on one peril (often flood or wildfire) and one line of business, then expanding.

What to do next: turning climate risk into underwriting advantage

Apollo’s move toward asset-level risk reviews reflects where the market is headed: granular extreme weather risk is becoming a standard input to valuation and financing. Insurers that keep climate risk trapped in annual reviews will feel it in quote turnaround, portfolio volatility, and capital efficiency.

If you’re building capability for 2026 planning, here’s what I’d prioritize:

- Pick one portfolio slice (e.g., middle-market property in a specific region) and implement asset identity + hazard enrichment.

- Integrate results into underwriting workflows (rating, referral rules, terms), not a separate dashboard nobody checks.

- Extend the model to supply chain dependencies for insureds with meaningful contingent business interruption exposure.

The big question for the next renewal cycle isn’t whether you’ll “consider climate risk.” You already are, even if it’s informal. The question is: will your approach be explainable, scalable, and fast enough to keep up with how investors and insureds are pricing risk today?