AbLecs target glyco-immune checkpoints that tumors use to suppress immunity. See how AI-driven drug discovery can design and optimize this new immunotherapy class.

AI-Designed AbLecs: Blocking Glycan Checkpoints in Cancer

A lot of cancer immunotherapy progress has come from a simple idea: if you remove the brakes, immune cells can do their job. The problem is that most “brakes” we target—PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4—are protein-centric. Tumors didn’t get the memo. Many of them suppress immunity using sugars on their surface and in their microenvironment, exploiting glycan–receptor interactions that are hard to see, hard to measure, and even harder to drug.

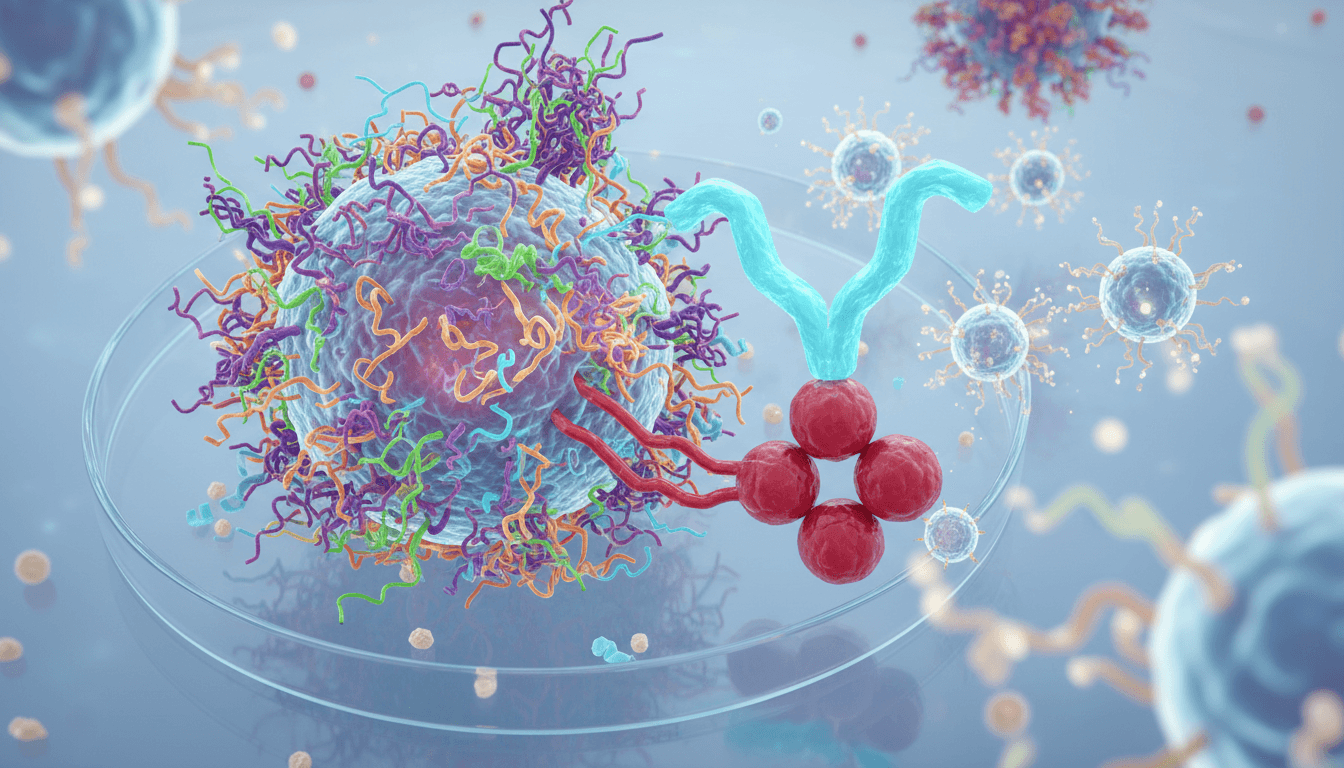

That’s why the recent work on antibody–lectin chimeras (AbLecs) is worth your attention. AbLecs are engineered molecules designed to bind and block immune-suppressive glycans—effectively treating certain glycan patterns as “glyco-immune checkpoints.” Early results show AbLecs can enhance antitumor immune responses in vitro and in vivo, and in some settings outperform conventional antibody therapies, including approved drugs.

From an AI in pharmaceuticals & drug discovery perspective, AbLecs are also a signal: oncology is moving toward multi-domain, multi-constraint biologics that don’t fit the old “one target, one antibody” playbook. Designing and optimizing these complex modalities is exactly where computational modeling and AI-driven drug discovery can pull real weight—especially when the target is a messy, heterogeneous “glycan cloud” rather than a neat protein pocket.

Glycan checkpoints: the immune suppression most teams ignore

Answer first: Many tumors evade immunity by displaying specific glycans (often sialylated structures) that engage inhibitory receptors on immune cells, damping activation, antigen presentation, and killing.

Protein checkpoints get the headlines because they’re comparatively straightforward to assay and target. Glycans are the opposite:

- They’re not templated by DNA in a one-to-one way. Glycosylation depends on enzyme expression, nutrient state, Golgi trafficking, and stress.

- They’re heterogeneous across clones, lesions, and time.

- They form patterns—clusters and presentations—rather than single “epitopes” in the classic sense.

A central axis here is sialic-acid–binding immunoglobulin-type lectins (Siglecs). Several Siglecs function as inhibitory receptors on immune cells. When tumors present abundant sialylated glycans, they can push macrophages and other cells toward immune-suppressive behavior. This is not abstract biology; work in glioblastoma, for example, has shown Siglec-9 can act as an immune checkpoint on macrophages, restricting T-cell priming and limiting immunotherapy response.

Here’s the practical point for drug discovery teams: glyco-immune checkpoints create resistance layers that can make PD-1 blockade look “fine on paper” but underperform clinically in certain contexts.

What AbLecs are (and why they’re different from another monoclonal)

Answer first: AbLecs combine antibody targeting with lectin-based glycan binding to block immune-suppressive glycans in the tumor microenvironment.

An AbLec is a chimera: part antibody, part lectin. The antibody component helps with targeting and localization. The lectin component provides specific glycan recognition—binding motifs that typical antibodies struggle to address reliably when the “antigen” is a variable carbohydrate landscape.

Conceptually, AbLecs aim to do two things at once:

- Find the right neighborhood (tumor tissue, immune interface, or a tumor-associated antigen context).

- Occupy/interrupt glycan-mediated inhibitory interactions that dampen immune activity.

That second part matters because many glycan interactions are low-to-moderate affinity but high avidity (lots of weak interactions that add up). A chimera that can present binding domains with the right geometry can disrupt those networks more effectively than a conventional antibody that recognizes one discrete protein epitope.

A line I keep coming back to is this: glycans are less like “targets” and more like “signals.” AbLecs are built to intercept the signal.

Why conventional antibodies often miss the glycan problem

Standard monoclonals can absolutely target glycan-associated antigens (gangliosides like GD2 are a classic example). But broad glycan-mediated immune suppression isn’t always about a single named antigen. It’s often about:

- density and distribution of sialylated glycans

- multivalent binding to inhibitory lectin receptors

- contextual presentation on many proteins and lipids

AbLecs are designed for that reality.

Where AI fits: AbLecs are a poster child for AI-driven biologics design

Answer first: AI helps because AbLecs require multi-parameter optimization—binding, specificity, stability, immunogenicity, geometry, and manufacturability—against targets that are heterogeneous and context-dependent.

If you’re building small molecules, you can often iterate around a relatively stable target structure. With AbLecs, you’re optimizing a system: antibody targeting + lectin binding + immune receptor engagement + tumor microenvironment biology.

This is where AI-driven drug discovery earns its keep, particularly across four problem areas.

1) Predicting glycan presentation and “what matters” clinically

Glycans vary by tumor type, patient, treatment history, and even biopsy site. AI models can integrate:

- transcriptomics/proteomics of glycosylation enzymes

- single-cell tumor microenvironment data

- spatial omics and imaging

- mass spectrometry glycomics (when available)

The goal isn’t academic completeness. It’s this: identify the glycan patterns most associated with immune exclusion, myeloid suppression, and checkpoint resistance, then prioritize AbLec formats most likely to block those patterns.

2) Designing lectin–glycan specificity without off-tumor chaos

A glycan binder that’s too broad can cause safety problems. Too narrow and it won’t generalize.

AI can help map and predict specificity by combining:

- structural modeling of lectin–glycan interactions

- sequence-to-binding prediction trained on glycan arrays

- multi-objective optimization to balance affinity vs. cross-reactivity

In practice, teams can use AI to propose lectin variants and then validate on glycan arrays and cell-based assays. The workflow matters: AI doesn’t replace the wet lab; it changes which experiments you run first.

3) Optimizing geometry and avidity (the under-discussed killer feature)

Many glycan interactions are governed by valency and spacing. AbLecs, by design, are modular—domain placement, linker length, domain orientation.

AI-guided structural ensembles and simulation can help answer questions like:

- What linker lengths maximize on-tumor avidity without increasing nonspecific binding?

- Which domain orientation favors receptor blockade at immune synapses?

- How do you avoid steric clashes that reduce effective binding in real tissue?

This is where “we engineered a binder” becomes “we engineered a therapeutic.”

4) De-risking developability early

AbLecs introduce developability risks: aggregation, expression yield, stability, and immunogenicity.

Modern developability models can flag liabilities early—before you sink months into a format that will never manufacture cleanly. If you’re aiming for leads, this is a big deal because it shortens the path from concept to a CMC-feasible candidate.

Practical implications for oncology teams: where AbLecs may land first

Answer first: AbLecs are most likely to show early clinical value in tumors with strong myeloid suppression and evidence of glycan-driven resistance to protein checkpoint blockade.

You don’t need to guess where glyco-immune checkpoints matter. Look for settings where:

- PD-1/PD-L1 response rates are modest

- macrophage-rich microenvironments dominate

- immune exclusion persists despite “inflamed” signatures

The literature around Siglec-7/9 inhibitory function in vivo and the Siglec–sialic acid axis as a checkpoint points to a plausible mechanism: blocking these interactions can restore antitumor immune activity and improve responses to existing immunotherapies.

Combination strategy is the default, not the exception

Most successful immuno-oncology modalities end up in combinations. Glycan checkpoint blockade fits that pattern because it addresses a different suppression layer than PD-1.

A pragmatic combination thesis looks like this:

- Protein checkpoint blockade lifts T-cell inhibitory signaling.

- Glycan checkpoint blockade (e.g., AbLecs) reduces myeloid-mediated suppression and improves antigen presentation/T-cell priming.

There’s precedent for synergy across distinct axes of immune suppression (for example, combinations involving CD47 blockade and other myeloid-focused strategies). AbLecs give teams another lever—one tuned to glycan biology.

Biomarkers: you’ll need better ones than “PD-L1 high”

If AbLecs succeed clinically, it won’t be because everyone treated responded. It’ll be because teams got serious about selecting patients.

Useful biomarker directions include:

- tumor sialylation signatures (glycomics or proxy panels)

- Siglec expression on tumor-associated macrophages

- spatial proximity of Siglec+ myeloid cells to tumor nests

- resistance signatures after PD-1 exposure

AI can help here too: multi-modal models can convert messy biomarker inputs into practical enrollment criteria.

A field reality check: what could slow AbLecs down

Answer first: The biggest risks are specificity/safety, translation of glycan biology across patients, and manufacturing complexity of a new chimera class.

I’m optimistic about the modality, but I wouldn’t pretend the path is easy.

- Safety risk: glycans are everywhere. You need the right specificity and the right localization so you’re not broadly perturbing normal immune regulation.

- Biology risk: glycan patterns shift under therapy pressure. Tumors can adapt by rewiring glycosylation enzymes.

- Operational risk: new formats increase CMC burden and comparability work, and they’ll face scrutiny on immunogenicity.

The teams that win won’t just have a nice binder. They’ll have a tight discovery-to-translation loop: glycomics → modeling → design → functional immunology → patient stratification.

What to do next if you’re building AI in drug discovery programs

Answer first: Treat glycan targeting as a data integration problem plus a modality design problem—then build a pipeline that can iterate quickly.

If you’re in pharma or biotech and evaluating whether glycan checkpoint programs belong on your 2026 roadmap, here are concrete next steps that tend to pay off:

- Inventory your data: Do you have tumor RNA-seq, single-cell, spatial, and any glycomics? If you don’t have glycomics, plan a targeted acquisition.

- Pick a tumor context where myeloid suppression is clearly limiting response.

- Prototype a “glycan suppression score” using multi-omics and clinical response labels.

- Stand up a design-test loop: lectin variant proposals → glycan array screening → immune cell functional assays → in vivo validation.

- Bake developability in early: don’t wait until after efficacy to learn it aggregates.

A personal take: most organizations over-invest in model sophistication and under-invest in fast, decision-grade experiments. The best AI programs are ruthless about shortening iteration cycles.

Where this is heading in 2026

AbLecs are a reminder that immunotherapy targets aren’t limited to proteins, and that “drugging glycans” is finally becoming realistic when paired with smarter modality design. For the AI in pharmaceuticals & drug discovery series, this is a clear storyline: as therapies become more modular and biologically context-dependent, AI becomes less about flashy predictions and more about engineering better decisions—what to build, how to tune it, and which patients to treat.

If you’re exploring AI-designed antibody formats, glycan checkpoint blockade is an unusually good proving ground: complex biology, measurable functional readouts, and a strong rationale for combination therapy.

If AbLecs continue to outperform conventional antibodies in rigorous models, the next question won’t be “can we target glycans?” It’ll be: which glycan interactions are worth blocking first, and how quickly can your discovery engine iterate toward a clinically testable candidate?