Small drones are being consumed like munitions. Treating them as ammunition helps scale AI-enabled autonomy, training, and supply chains without bureaucracy.

Treat Small Drones Like Ammunition—Or Lose Tempo

A modern infantry unit can burn through small drones the way it burns through magazines: issue, use, replace, repeat. Ukraine made that reality impossible to ignore—its small-drone output reportedly jumped 900% to about 200,000 per month in 2025, and front-line units routinely treat quadcopters and first-person-view (FPV) drones as disposable battlefield tools.

Most Western militaries still treat the same drones like sensitive property: serialized equipment, hand receipts, maintenance tickets, and investigations when one doesn’t come back. That mismatch isn’t just bureaucratic friction. It’s a readiness problem.

Here’s the stance I’ll defend: for small, rucksack-portable drones, the U.S. should formalize what combat has already proven—treat them as ammunition. And because this is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, I’ll go a step further: the “ammo model” is also the fastest path to scaling AI-enabled autonomy, mission planning, and sustainment without drowning units in paperwork.

The core idea: drones belong in the ammunition enterprise

Answer first: Small drones should be managed like munitions because they’re consumable, high-turnover, and operationally expected to be lost—and the ammunition system already exists to forecast, issue, track, and replenish expendables at scale.

Right now, many units buy drones with operational funds, track them like gear, and improvise repair pipelines. When a drone gets shot down, lost to electronic warfare, or crashes into a tree, the administrative tail can be absurdly out of proportion to the value of the asset.

Ammunition logistics is built for the exact opposite assumption: items will be expended. There’s an auditable process—forecast, draw, expend, turn in residue—that tolerates loss by design.

Why the “property model” fails at scale

If the Army truly moves toward very large inventories—reporting has suggested ambitions on the order of a million drones—the property approach collapses under its own weight. Not because soldiers can’t be accountable, but because accountability mechanisms designed for durable gear aren’t compatible with consumables.

A simple, snippet-worthy way to say it:

If a squad leader has to write a loss memo for a drone intended to be lost, the system is misclassifying the weapon.

Treating small drones as ammunition fixes the classification error.

What “drones as ammunition” looks like in practice

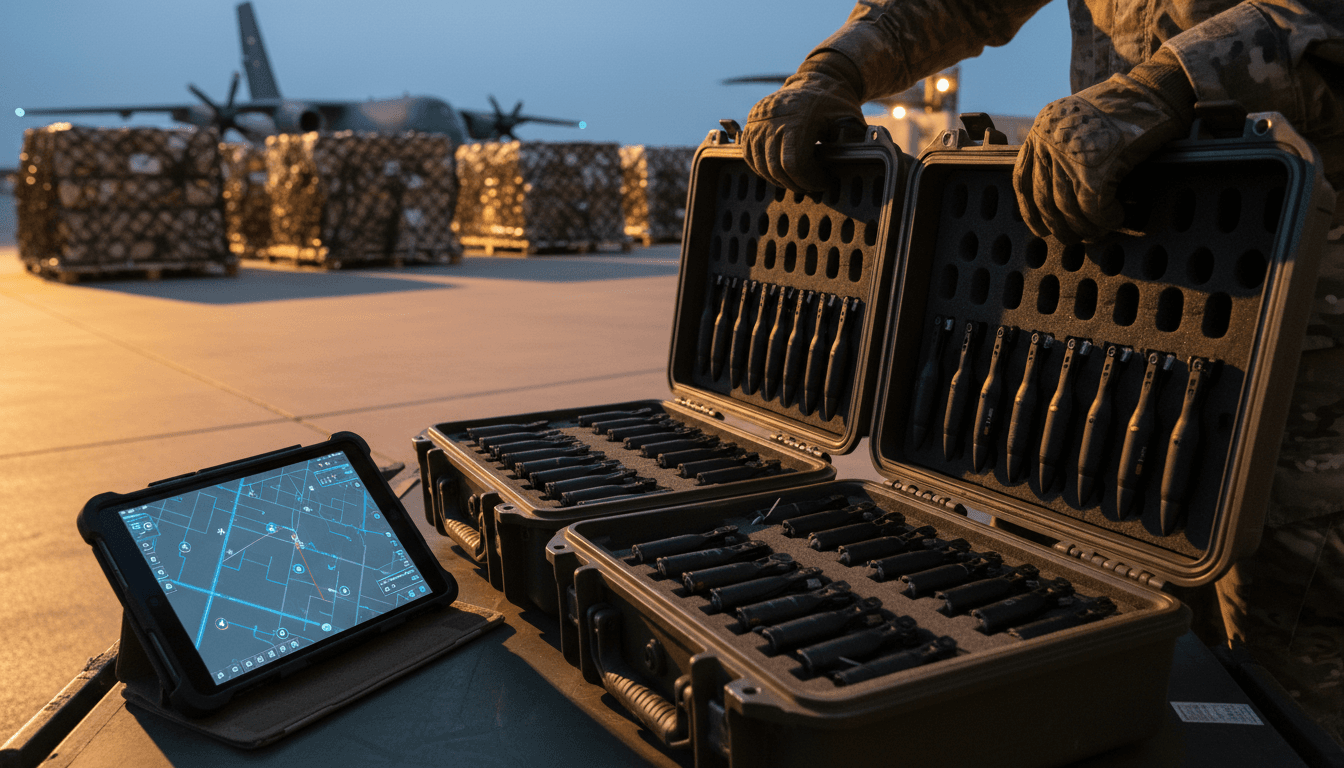

Answer first: Put the airframe + payload kit into ammunition channels, while keeping controllers and mission-enabling gear on the unit property book.

This is the clean separation that makes the model work:

- Ammunition-like (consumable): the drone airframe, swappable payload modules, one-time-use components, packaging/dunnage

- Equipment-like (durable): controllers, antennas, training devices, tablets/phones used for mission apps, repair tools

That’s not theoretical—it mirrors how expensive missiles are already handled. Units maintain the launch device; the round itself is issued, expended, and accounted for as ammunition.

The loop units actually need: forecast → issue → fly → turn in

The ammo enterprise is built around predictable loops. That matters because drones aren’t just “bought.” They’re consumed during training and burned fast in combat.

A workable drone-ammo loop looks like this:

- Forecast: Units request quantities by standardized identifier (the equivalent of a munition code), aligned to training plans and readiness tasks.

- Issue: Drones are drawn from a controlled holding area with seals/lot tracking and basic inspection.

- Fly/Expend: Drones are used, lost, recovered, or returned.

- Turn in: Unused drones return for reissue; damaged items return for disposition; packaging and batteries are handled under defined rules.

The big win is cultural: drones stop being “special projects” and start being routine. That’s how you get repetition, proficiency, and honest readiness reporting.

Standardize by mission role, not by brand

Answer first: The Army should buy and issue drone families by role-based categories (recon, FPV training/attack, etc.) so units can train consistently while industry competes inside clear lanes.

Procurement conversations love brand names. Operations don’t.

In real units, what matters is whether the drone fills a role reliably:

- Recon micro/mini quadcopter: quick look, route check, target confirmation

- FPV drone: high-volume operator reps, kinetic employment in some concepts

- Specialty payload variants: short-range EW sensing, signal relay, low-light/thermal, mapping

Role-based “families” make the ammo model viable because you can:

- assign each family a stable identifier for forecasting and issue

- swap vendors without rewriting the unit’s entire training pipeline

- run controlled experimentation in small tranches without breaking logistics

Controllers are the hinge point

Treating drones as ammunition only works if controllers are standardized enough that a platoon can replace a dead drone quickly.

If every new airframe requires a new controller UI, new firmware rituals, and new certification events, you’re back to bespoke gear management. The better approach is:

- common controller interfaces that can bind to multiple issued drone families

- stable integration with mission apps (many units already rely on mobile mission tools)

- disciplined software change control so updates don’t reset training

This is where the AI in Defense & National Security thread shows up in force: AI-enabled autonomy is useless if the human-machine interface keeps changing faster than units can train.

AI makes the “ammo model” more urgent—not less

Answer first: AI increases drone consumption because autonomy enables more missions, more coverage, and faster cycles—so logistics must be designed for scale.

As autonomy improves, drones stop being single-purpose gadgets and become a repeatable, distributed sensing-and-effects layer. That expands demand in three ways:

- More missions per day: AI-assisted planning compresses the time from tasking to launch.

- More operators who can be “good enough”: better autonomy and decision aids reduce the skill barrier.

- More acceptable losses: when a $2,000–$5,000 drone replaces a far more expensive munition in certain contexts, commanders will use them aggressively.

The hard truth: AI capabilities scale only when sustainment scales. If the supply chain can’t feed the force, autonomy becomes a lab demo.

AI for sustainment: forecast accuracy and industrial predictability

The ammo model also unlocks a more realistic industrial base rhythm.

When demand is ad hoc—emergency buys, one-off contracts, uneven unit funding—manufacturers whipsaw between surge and starvation. Under an ammunition-style system, demand becomes:

- forecastable (allocations drive planned draws)

- auditable (usage rates become real data, not guesses)

- optimizable (AI can model burn rates by unit type, terrain, season, and threat)

Once you have clean consumption data, you can apply AI to the unglamorous but decisive work:

- predicting battery attrition by temperature and charging behavior

- identifying failure modes by lot and component supplier

- optimizing storage and distribution to reduce dead-on-arrival rates

- recommending training mixes (sim vs live) that maximize proficiency per dollar

This is how AI becomes a readiness multiplier without pretending it replaces strategy.

A realistic implementation plan (90 days to prove it)

Answer first: Start with a pilot at a few installations, define two drone families, and run them through an ammunition-style issue/turn-in process with tight feedback loops.

Big reorganizations die in committees. A pilot can force clarity fast.

Step 1: Create two “drone-as-ammo” families

Start narrow:

- Family A: small recon quadcopter (day/night variants if needed)

- Family B: FPV training/attack drone (with separate training configuration if policy requires)

Define what’s consumable, what’s durable, and what the turn-in requirements are.

Step 2: Package like munitions, not like consumer electronics

Small drones should arrive in weather-resistant, shock-tolerant cases, with standardized contents and checklists. Units should be able to open a case and know:

- what’s inside

- what’s single-use vs reusable

- what requires turn-in vs disposal

Step 3: Treat batteries like operationally sensitive consumables

Batteries are the quiet failure point.

Ammunition-style handling can impose discipline:

- storage rules (temperature, charge levels)

- inspection intervals

- quarantine processes for swollen or damaged packs

If you want AI-enabled drones to be reliable, you start by getting battery management boring and consistent.

Step 4: Build a training ladder that doesn’t waste live drones

Units shouldn’t be forced into “all-live, all-the-time.” A sensible progression:

- Desktop/VR simulators for basic stick skills and emergency procedures

- low-cost trainers for early reps and indoor work

- ammo-issue drones for field realism, EW exposure, and mission rehearsal

The ammo model supports this because allocations create budget ceilings and planning discipline.

Common objections—and the clean answers

Answer first: The biggest objections (innovation speed, cost, and classification complexity) are real, but the ammunition model handles them better than the status quo.

“Innovation is too fast for standardized families”

The ammo enterprise already accommodates variants and controlled experimentation. The trick is to standardize roles and interfaces, then iterate inside the lanes.

A practical rule:

Standardize the “plug” (controller/software interface) and the mission role. Compete the “bulb” (airframe/payload) frequently.

“This will increase spending”

It will increase planned spending—and reduce surprise spending.

Ammunition allocations create predictable ceilings. Commanders can see their burn rates, and higher headquarters can compare usage across formations. That transparency is how you control cost without starving training.

“Are drones really comparable to munitions?”

Yes, for small systems. Many are priced in the low thousands of dollars, comparable to some conventional rounds, and they’re expected to be expended or lost.

And the ammo system already manages complex, expensive items. The question isn’t whether drones are identical to shells; it’s whether the enterprise is designed for consumption at scale. It is.

What this means for AI in Defense & National Security

Answer first: Treating drones as ammunition is the fastest institutional move the U.S. can make to scale AI-enabled autonomy, mission planning, and resilient logistics.

AI in national security often gets framed as algorithms and autonomy. The more decisive story is systems: training systems, sustainment systems, and procurement systems that let new capabilities spread across the force.

If small drones remain “property,” AI-enabled drone concepts will stay trapped in pockets of excellence—units with the time, leadership, and budget hacks to keep them flying. If small drones become “ammunition,” you can normalize mass training, harden supply chains, and collect the operational data that makes AI better.

If you’re responsible for modernization, sustainment, or operational planning, the next step is straightforward: run a pilot that uses an ammunition-style issue and turn-in process for two small-drone families, and measure readiness outcomes—not paperwork completion.

A forward-looking question worth sitting with: when autonomy makes one operator capable of managing multiple drones, will your logistics system be ready to feed that tempo—or will it cap your advantage?