Quantum magnetic navigation is emerging as a serious GPS backup. Here’s why the Pentagon is testing it—and where AI makes it operationally trustworthy.

Quantum Magnetic Navigation: A GPS Backup Pentagon Tests

GPS is a single point of failure in more U.S. missions than most people want to admit.

Not because GPS is “fragile” in the everyday sense—it’s extraordinarily capable—but because jamming, spoofing, and localized denial are now routine features of modern conflict and gray-zone competition. If you’re running precision maneuver, autonomous swarms, or time-sensitive targeting, “GPS might not be there” isn’t a niche edge case anymore. It’s a planning assumption.

That’s why the Pentagon’s growing interest in quantum sensing for magnetic navigation deserves attention—especially for anyone tracking the “AI in Defense & National Security” wave. The interesting part isn’t just the sensor hardware. It’s the software problem the Defense Department is signaling it wants solved: How does a platform know when its GPS alternative is trustworthy in real time?

Why magnetic navigation is back on the table

Answer first: Magnetic navigation is attractive because it uses a natural signal—Earth’s magnetic field—that can’t be jammed like a satellite signal, and it can serve as a meaningful layer in a resilient PNT (positioning, navigation, and timing) stack.

Military navigation lives and dies by PNT. When PNT degrades, everything cascades:

- Strike and ISR platforms lose geolocation confidence

- Networked fires suffer from timing errors

- Autonomous systems become conservative (or dangerous)

- Logistics and maneuver slow down because commanders can’t trust the map

Magnetic navigation (often shortened to magnav) isn’t new conceptually. A compass is magnetic navigation in its simplest form. The modern twist is using high-sensitivity magnetometers—including quantum-enabled sensors—to detect subtle variations in Earth’s crustal magnetic anomalies and compare them against magnetic maps.

The promise: in GPS-denied environments, an aircraft or drone can estimate its position by matching measured magnetic “fingerprints” to a stored reference.

The catch: those fingerprints aren’t equally distinctive everywhere, and real platforms are noisy, vibrating, metallic environments that contaminate measurements.

The operational driver: GPS alternatives that work under stress

If you’re building a serious navigation architecture for contested operations, you don’t pick one “GPS replacement.” You build a portfolio:

- Inertial navigation (INS)

- Terrain referenced navigation (TRN)

- Vision-based navigation

- Signals of opportunity

- Celestial navigation (in some scenarios)

- Magnetic navigation

Magnav is appealing because it’s passive and local. But its usefulness depends on an uncomfortable truth: sometimes the magnetic signal is great, and sometimes it’s lousy—and you need to know which is which while you’re flying.

What the Pentagon’s new test program signals

Answer first: The Defense Department is pushing beyond lab-style demos toward operationally relevant testing—across aircraft types, routes, and conditions—because scaling GPS backups requires confidence metrics, not just accuracy claims.

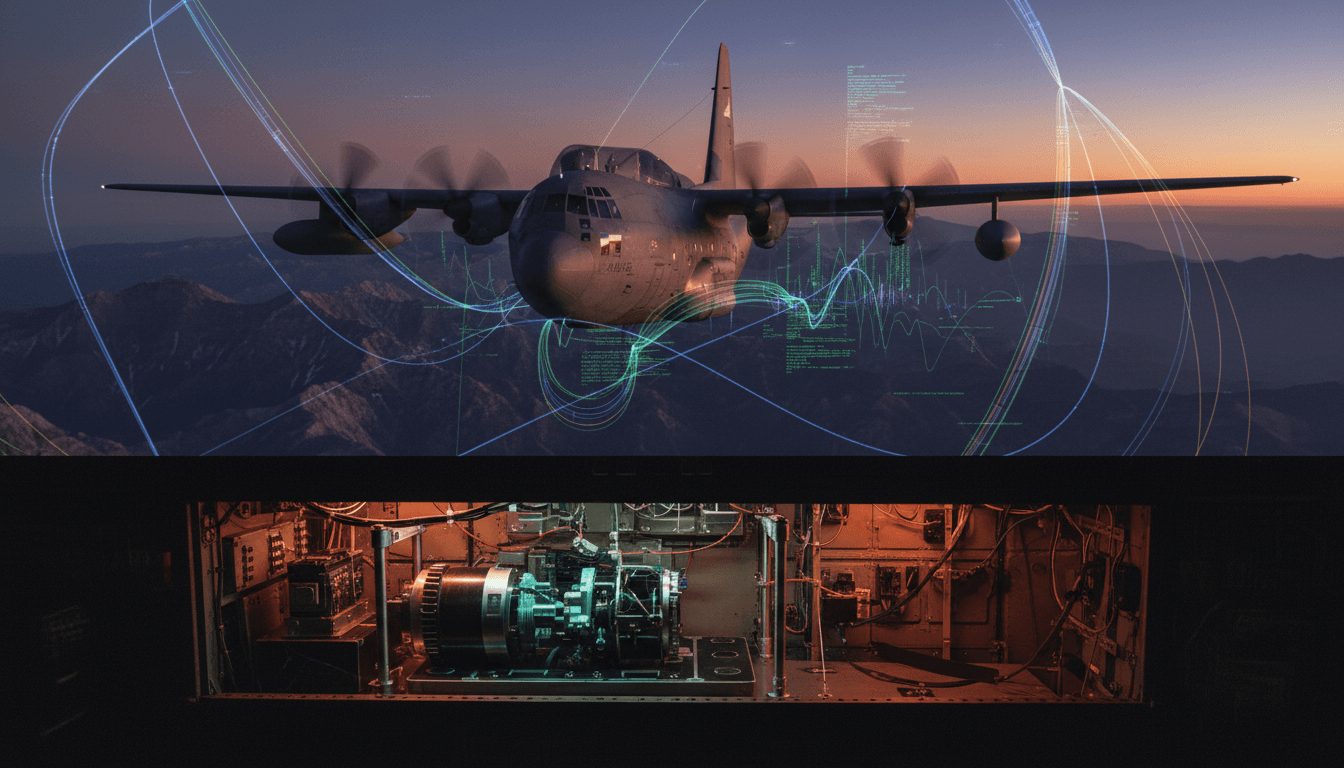

A recent Pentagon agreement brings SandboxAQ into the Defense Innovation Unit’s Transition of Quantum Sensing (TQS) program to test the company’s AQNav software across a range of aircraft and conditions. This builds on earlier Air Force testing on C-17 aircraft during exercises.

From a defense acquisition perspective, that’s a meaningful shift:

- Demos prove feasibility.

- Broad field testing proves deployability.

DIU’s interest suggests the problem definition is maturing from “Can we navigate with magnetometers?” to “Can we operationalize a magnetic navigation capability that commanders will trust?”

That trust is the core issue. Nobody cares about a backup navigation mode that’s occasionally brilliant but unpredictably wrong.

The real bottleneck: knowing when you’re wrong

Traditional navigation performance metrics (civil aviation’s RNP, or military Circular Error Probable concepts) can be misleading for magnav because the error characteristics vary dramatically by geography and conditions.

Magnetic navigation has “good days” and “bad days” based on:

- Local anomaly richness (some areas are magnetically “flat”)

- Map quality and resolution

- Platform electromagnetic interference

- Sensor placement and calibration

- Altitude and flight profile

In other words, a single accuracy number isn’t enough. What you need is an estimate of confidence.

Where AI fits: the “trust layer” for quantum sensing

Answer first: AI is valuable in magnetic navigation because it can estimate uncertainty, detect degraded sensing conditions, and fuse magnetic signals with other navigation sources—turning raw sensing into actionable PNT.

Most people hear “quantum sensing” and picture exotic physics. In defense programs, the differentiator often ends up being far more practical: software that makes imperfect sensors usable at scale.

Here’s what AI and modern probabilistic modeling can do for magnav systems:

1) Measurement quality estimation (real-time “is this sensor behaving?”)

A platform needs to detect when the magnetometer is being polluted by onboard noise or external anomalies.

AI methods can help identify signatures of degraded measurements—think of it as anomaly detection for navigation health.

2) Map mismatch handling (when the world doesn’t match your reference)

Magnetic maps are not uniformly “well-sampled.” High-quality maps are expensive to produce because they often require specially instrumented survey flights.

AI can help:

- Interpolate between sparse measurements

- Estimate the reliability of a local map segment

- Quantify how much the map uncertainty contributes to position uncertainty

3) Sensor fusion that’s honest about uncertainty

This is the part I’ve found many teams underinvest in: fusion isn’t just combining signals—it’s managing contradictions.

A robust architecture will fuse:

- INS (drifts over time but is smooth)

- Magnav (can be absolute but geographically variable)

- Vision/TRN (great in some terrain/visibility, weak in others)

The fusion engine must answer: Which source should I trust right now, and by how much? AI can support this by learning context-dependent weighting and by maintaining calibrated uncertainty estimates.

A GPS alternative that can’t quantify its own confidence is operationally dangerous.

4) Autonomous operations: navigation is the first safety requirement

Autonomy discussions often start with perception and targeting. In real deployments, navigation comes first.

Small uncrewed systems can’t rely on continuous comms or remote piloting in contested environments. If you want autonomous platforms that can route, re-route, and coordinate, you need PNT that is:

- resilient

- locally available

- and measurable in terms of confidence

Magnav doesn’t solve autonomy by itself—but it can be a key layer in an autonomy-ready PNT stack.

Why magnetic navigation is hard in the real world

Answer first: Magnav succeeds only when sensors, maps, and validation metrics work together; failure in any one of those makes performance look good in tests and unreliable in operations.

There are three practical hurdles that trip programs up.

Map reality: “well-sampled” is expensive

A high-quality magnetic reference map can reach tens of meters of accuracy under controlled survey conditions, but building those maps broadly is costly and time-consuming.

That leads to uneven coverage—great maps in some corridors, weaker maps elsewhere. The operational implication is blunt: magnav may be mission-route dependent.

Platform integration: aircraft are magnetically noisy

A magnetometer on an aircraft isn’t measuring only Earth’s crustal field. It’s also measuring:

- electromagnetic emissions

- structural magnetic effects

- current flows from onboard systems

- vibrations and mounting artifacts

Integration engineering matters as much as sensor sensitivity.

Validation: old metrics can flatter you

If you score a system using a metric that doesn’t reflect “magnetic weather,” you’ll ship something that looks compliant but fails in edge conditions.

One approach emerging from recent work is to compute statistics that describe whether errors stay within knowable bounds—effectively a navigation “cloudiness” report that tells the user how much to trust the solution.

That’s the kind of “trust layer” the Pentagon needs if it wants to field GPS backups beyond boutique units.

How defense teams should evaluate quantum sensing + AI PNT solutions

Answer first: The best evaluation criterion is not peak accuracy—it’s predictable performance, calibrated confidence, and integration into a multi-layer PNT architecture.

If you’re in a program office, an operational test community, or a defense prime partnering with a sensing vendor, here are decision filters that actually hold up.

Ask for confidence outputs, not just position outputs

A deployable system should provide:

- position estimate

- uncertainty bounds (and evidence they’re calibrated)

- health indicators (sensor/mapping/fusion status)

If the system can’t explain when it’s degraded, it’s not ready for autonomy or weapons-grade navigation.

Test across magnetic “good” and “bad” regions

You want a test plan that includes:

- feature-rich anomaly areas

- magnetically bland areas

- different altitudes and flight profiles

- different platform configurations and power states

Magnav that only works in a cherry-picked route is a science project.

Require graceful degradation and clear fallbacks

Resilient PNT is a stack. When magnav degrades, the platform must:

- revert to INS + constraints

- increase reliance on vision/TRN where possible

- request human intervention if in a safety-critical phase

The right question is: How does the system behave when it’s wrong?

Evaluate cyber and supply-chain realities

Navigation systems are security systems. For AI-enabled PNT, pay attention to:

- model update pathways and signing

- sensor calibration integrity

- tamper resistance

- attack surfaces in fusion software

A GPS backup that introduces a new spoofing or malware path is self-defeating.

What this means for the “AI in Defense & National Security” roadmap

Answer first: Quantum sensing matters to AI-enabled defense because it strengthens the weakest link in autonomy—trusted navigation in contested environments—while pushing the DoD toward measurable, testable confidence metrics.

Over the past few years, the conversation in defense AI has shifted from “Can the model detect objects?” to “Can the system be trusted under operational constraints?” Navigation is part of that trust story.

The Pentagon’s interest in magnetic navigation via quantum sensing is also a quiet admission: resilience beats elegance. No single technology will replace GPS everywhere. The winning approach will be a layered PNT architecture where AI helps decide what to trust in the moment.

If you’re building autonomous ISR, collaborative combat aircraft concepts, or attritable one-way systems, you should treat resilient PNT as a core dependency—not a subsystem you bolt on late.

For teams trying to move from prototypes to fielded capability, the near-term opportunity is clear: build the trust layer—the metrics, the monitoring, and the fusion logic that makes alternative navigation usable by operators, not just engineers.

Where do you think the first large-scale deployments land: cargo aircraft and tankers, or smaller uncrewed platforms that can accept more navigation risk?