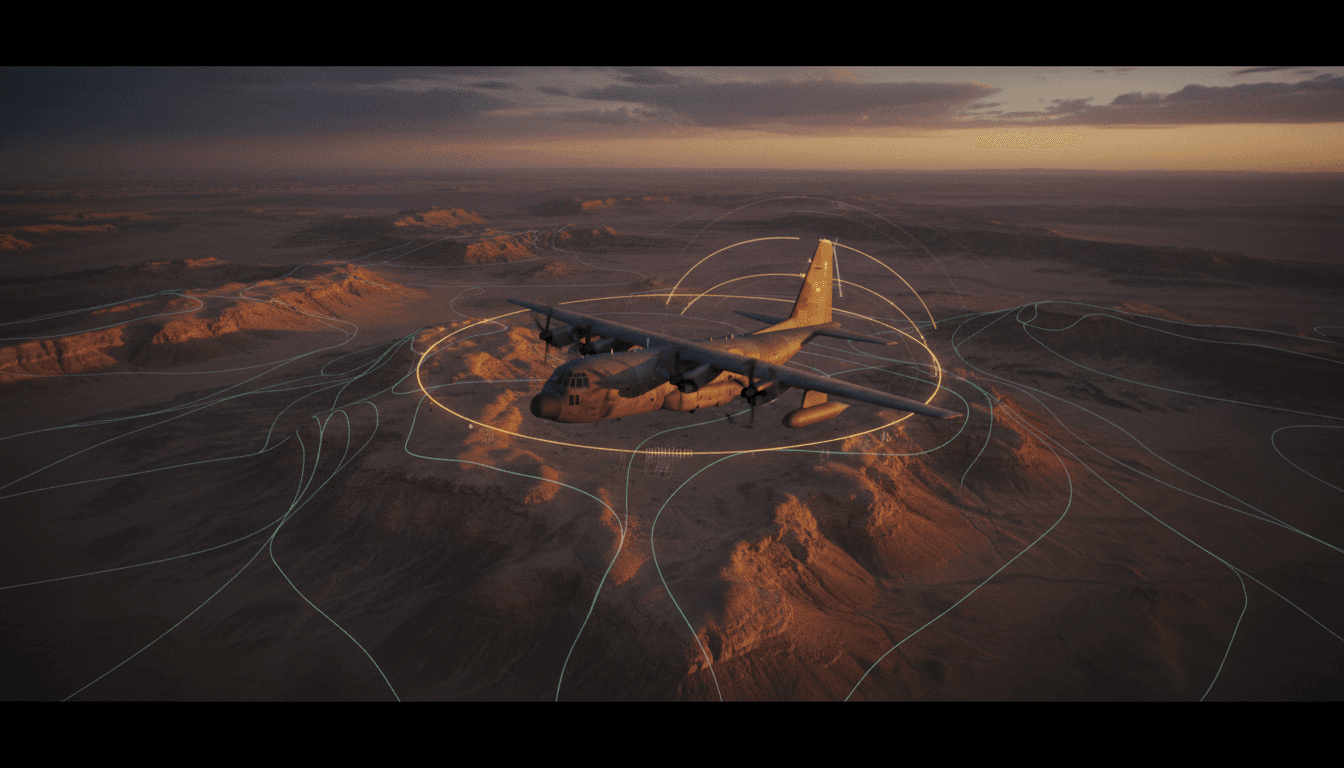

Quantum magnetic navigation is emerging as a GPS backup. Here’s how AI makes magnav operational through confidence scoring, fusion, and resilient PNT design.

Quantum Magnetic Navigation: The AI Angle for Defense

A GPS receiver is one of the most useful “single points of failure” in modern military operations. When positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) are denied—through jamming, spoofing, or space-layer disruption—missions don’t just get harder; they get riskier in ways that cascade across targeting, deconfliction, logistics, and autonomy.

That’s why the Pentagon’s expanding interest in quantum sensing for magnetic navigation is worth paying attention to—especially if you track AI in defense & national security. The headline isn’t “quantum replaces GPS.” The real story is more practical: the Department of Defense is funding systems that can tell you when they’re trustworthy, and AI is central to that.

The Defense Innovation Unit’s Transition of Quantum Sensing (TQS) effort—testing SandboxAQ’s AQNav software across multiple aircraft and operating conditions—signals a shift in mindset: navigation resilience isn’t about a single exotic sensor. It’s about sensor fusion, performance prediction, and graceful degradation. Those are AI problems as much as they are physics problems.

Why magnetic navigation is back in the conversation

Answer first: Magnetic navigation is resurfacing because it offers a passive, potentially jam-resistant signal source that can support GPS-alternative PNT when satellites are contested.

Magnetic navigation (often shortened to “magnav”) exploits the Earth’s magnetic field—specifically the irregular “fingerprints” caused by variations in the planet’s crust. A basic compass uses the same phenomenon, but it’s nowhere near precise enough for modern flight routes, weapons employment, or autonomous mission planning.

Quantum sensors change the equation because they can measure magnetic fields with extreme sensitivity. In principle, if you can measure the local magnetic field precisely and compare it to a reference map, you can estimate where you are.

The catch: the map and the platform are the hard parts

Magnav’s biggest obstacle isn’t “Can we measure magnetism?” It’s “Can we know what the measurement means right now?”

Two realities collide:

- The magnetic environment varies by geography. Some regions have strong, distinctive gradients; others are magnetically “flat” or noisy.

- Aircraft (and drones) are magnetically messy. The platform itself—wiring, power systems, payloads—can contaminate a magnetometer unless you control for it.

If you’ve ever worked with AI-enabled perception on autonomous systems, this should feel familiar: the world isn’t uniform, and sensors don’t behave consistently outside scripted conditions.

The Pentagon’s real bet: “navigation that knows its own limits”

Answer first: The most important technical problem in magnetic navigation is estimating confidence—detecting when the system is accurate, when it’s drifting, and when it’s effectively guessing.

The RSS source highlights a key issue: traditional navigation performance metrics can mislead when applied to magnav. Systems like Required Navigation Performance (RNP) or Circular Error Probable (CEP) were built around sensors whose error behaviors are comparatively well-characterized under many conditions. Magnav flips that: performance depends heavily on location, altitude, and the quality of the reference map, plus platform-specific noise.

This is where SandboxAQ’s approach is strategically interesting. Their work (including a late-2025 journal paper by their navigation engineering lead) focuses on computing whether the error stays within “knowable bounds”—a practical statistic that acts like a reliability score for the navigation solution.

Here’s the defense relevance: a backup navigation method isn’t useful if it can’t declare, in real time, “I’m good” or “I’m degraded.” Commanders and autonomous agents need systems that can say:

- How accurate am I right now?

- How quickly am I getting worse?

- What’s driving the error: the map, the sensor, the platform, or the environment?

That’s not a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between resilient operations and false confidence.

A resilient PNT stack isn’t defined by its peak accuracy. It’s defined by how clearly it communicates uncertainty under stress.

Where AI fits: from raw magnetics to usable PNT

Answer first: AI makes magnetic navigation operational by modeling uncertainty, compensating for platform noise, and enabling sensor fusion with inertial and other GPS-alternative signals.

A common misconception is that magnav is a “sensor problem” and AI is a separate “software problem.” In practice, magnav becomes viable when AI and probabilistic estimation turn messy signals into actionable navigation.

1) AI helps predict “magnetic observability” by region

Magnav works best where the Earth’s crust creates distinctive magnetic patterns. Some areas provide strong matching signals; others don’t. AI-based models can help estimate observability—how uniquely a measured magnetic signature corresponds to a location—so mission planners can anticipate where magnav will be reliable.

In operational terms, this enables planning like:

- Route A: GPS-denied segment crosses a magnetically rich corridor → magnav supports dead reckoning

- Route B: magnetically ambiguous region → rely more on inertial + terrain referencing + cooperative navigation

This is mission planning as a data science exercise.

2) AI can separate platform-induced noise from the Earth signal

Aircraft are full of magnetic interference. Changing payload configurations, power draw, or even maintenance differences can shift signatures. AI models can learn platform-specific noise patterns and improve the “cleanliness” of measurements—especially when paired with careful calibration procedures.

If you’ve deployed AI in contested ISR, you know the pattern: the model isn’t replacing physics; it’s compensating for the chaos that makes physics hard to apply at scale.

3) AI enables sensor fusion and graceful degradation

Magnav isn’t a “GPS clone.” The most credible near-term architecture is a multi-sensor PNT stack:

- Inertial navigation (IMU)

- Magnetic navigation (magnav)

- Barometric + radar altimetry

- Terrain referencing / scene matching

- Signals of opportunity (when available)

- Cooperative navigation (formation sharing)

AI (and classical Bayesian filtering) helps weight each input based on current confidence. When GPS is jammed, you don’t switch to one backup—you rebalance across the stack.

This matters even more for autonomy. A one-way drone that can’t explain its nav confidence will either:

- Over-trust a bad estimate and miss, or

- Become overly conservative and fail the mission.

What the DIU TQS partnership suggests about DoD priorities

Answer first: DoD is prioritizing transition-ready prototypes that can be tested across diverse operational conditions—not just controlled demonstrations.

The DIU’s TQS field-testing model is a signal. Programs that survive the “cool demo” phase are the ones that:

- Work across multiple aircraft types

- Survive different flight profiles and environmental conditions

- Provide measurable, auditable performance

- Integrate into existing avionics and mission workflows

This is where many emerging technologies stall. They prove accuracy in a narrow test box, then collapse when confronted with fleet variation, maintainability, and integration realities.

Magnav is especially vulnerable to this trap because maps, calibration, and platform configuration can dominate outcomes. DIU’s emphasis on broad testing is the right move. If you can’t characterize performance across conditions, you can’t deploy responsibly.

Practical takeaways for AI and defense tech leaders

Answer first: If you’re building AI for national security, treat navigation resilience as an uncertainty-management problem and design for integration, not novelty.

Here are the tactics I’d want in place if I were evaluating (or building) AI-enabled GPS alternatives in 2026 planning cycles.

1) Demand “confidence outputs,” not just accuracy claims

Ask vendors and internal teams for:

- Real-time uncertainty estimates (not just average error)

- Failure-mode detection (when/why the system degrades)

- Confidence calibration metrics (does 90% confidence really mean 90%?)

If the system can’t tell you when it’s wrong, it’s not mission-ready.

2) Test against operational diversity, not best-case conditions

A credible test plan includes:

- Different aircraft or drone configurations (payload swaps matter)

- Varying altitudes and maneuvers

- Electromagnetic interference scenarios

- Magnetically “good” and “bad” geographic regions

This is the navigation version of adversarial testing in AI.

3) Plan for “PNT as a stack”

Even if magnav performs well, it should be integrated as one layer of a resilient PNT architecture. Teams should design interfaces and autonomy behaviors around:

- Sensor handoffs

- Weighted fusion

- Degraded-mode behaviors (what does the platform do when confidence drops?)

The best autonomy programs I’ve seen treat degraded navigation as a first-class design constraint, not an edge case.

4) Don’t ignore data operations: maps, updates, validation

Magnav lives or dies on reference maps and validation workflows. You’ll need processes for:

- Map provenance and update cadence

- Regional performance characterization

- “Drift monitoring” across time (magnetic environments shift slowly, platforms shift faster)

If your organization isn’t ready to manage that data lifecycle, the sensor won’t save you.

Q&A: what readers usually ask about quantum sensing and GPS alternatives

Will quantum magnetic navigation replace GPS?

No. The operational goal is GPS resilience, not replacement. Expect magnav to complement inertial navigation and other GPS-alternative PNT methods.

Is this mainly a quantum hardware story or an AI story?

It’s both, but deployment hinges on software. Quantum sensors can measure subtle fields; AI turns those measurements into usable navigation with confidence estimates.

What’s the most important metric for magnav in real operations?

Not peak accuracy—trustworthy uncertainty. A system that reports “I’m within X meters with Y% confidence” (and is consistently right about that) is far more valuable than one that occasionally performs brilliantly.

What this means for the “AI in Defense & National Security” series

Navigation is becoming an AI discipline. That might sound strange until you notice the throughline across autonomy, ISR, and cyber: the winners aren’t the systems with the flashiest models—they’re the ones that operate reliably under messy conditions and communicate uncertainty in a way humans and machines can act on.

Quantum sensing for magnetic navigation is a concrete example of that shift. The Pentagon’s interest isn’t hype; it’s a recognition that GPS-denied operations are now a baseline planning assumption, and AI-enabled sensor fusion is the practical route to resilience.

If you’re responsible for autonomy, mission planning, or platform integration, the near-term question isn’t “Should we bet on quantum?” It’s: Do we have a PNT architecture that can degrade gracefully, quantify risk in real time, and keep operating when the obvious signals disappear?