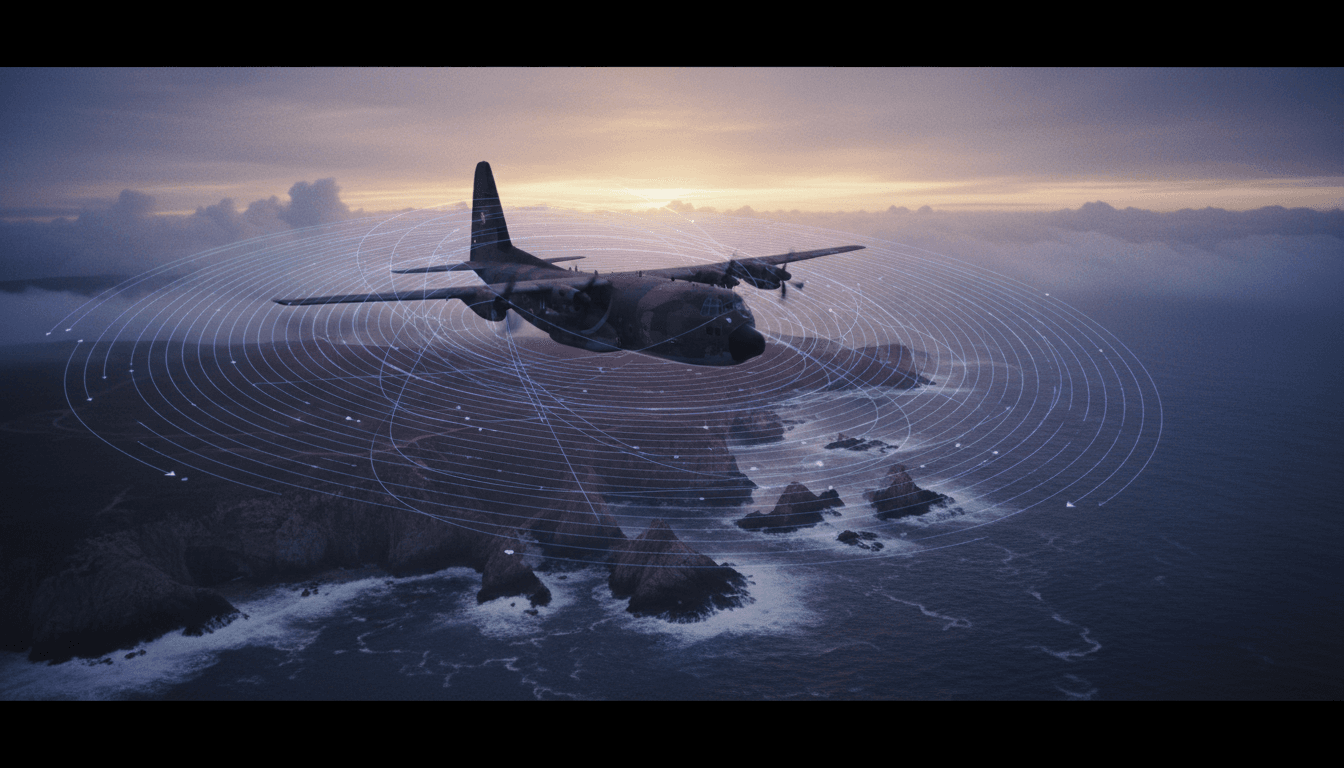

Quantum magnetic navigation is emerging as a practical GPS backup for defense. Here’s why the Pentagon’s testing matters for AI-enabled autonomy and mission assurance.

Quantum Magnetic Navigation: The Pentagon’s AI Bet

GPS isn’t “down” until it’s too late. In real operations, you often don’t get a clean warning that spoofing, jamming, or subtle timing drift has started to poison your navigation solution—especially when multiple systems are fused and the cockpit still shows a plausible position.

That’s why the Pentagon’s interest in quantum magnetic navigation is more than a science project. It’s a practical push toward positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) resilience—and it sits right in the middle of the broader AI in Defense & National Security story: autonomy, mission planning, and contested-spectrum operations all collapse if platforms can’t trust where they are.

A recent Defense Department move signals momentum: the Defense Innovation Unit expanded testing under its Transition of Quantum Sensing (TQS) program to evaluate SandboxAQ’s AQNav magnetic navigation software across multiple aircraft and operating conditions. The interesting part isn’t just the sensor. It’s the operational problem they’re trying to solve: How does a system know when it’s right—and when it’s wrong—without GPS as the referee?

Why GPS-denied navigation is an AI problem, not just a sensor problem

The direct answer: In GPS-denied environments, navigation becomes an uncertainty management challenge—exactly where AI excels when it’s designed and governed correctly.

A lot of people hear “quantum sensing” and picture exotic hardware replacing GPS. That’s not how this gets fielded. Modern PNT resilience is a stack:

- Sensors (magnetometers, IMUs, barometers, celestial, terrain, RF signals of opportunity)

- Models (maps, geomagnetic models, error models)

- Algorithms (filtering, sensor fusion, anomaly detection)

- Assurance (real-time confidence scoring, fault isolation, operator cues)

The dirty secret: the best sensor in the world is still operationally dangerous if it can’t reliably tell you when it’s degraded. Autonomy doesn’t fail only when estimates are wrong—it fails when a platform acts confidently on bad estimates.

In other words, the “AI” value here is less about fancy pattern recognition and more about trustworthy estimation:

- Detecting when magnetic measurements are contaminated by aircraft-generated electromagnetic noise

- Recognizing when the local magnetic map is poorly sampled or non-unique

- Assigning bounded error to a position estimate (so mission systems can decide what to do next)

That’s why the Pentagon’s attention is drawn to software methods that quantify navigation performance, not just raw sensing.

Quantum magnetic navigation, explained like you’ll brief it

The direct answer: Magnetic navigation works by matching measured magnetic field signatures to a magnetic “map” to estimate location—similar in concept to terrain contour matching, but using magnetism instead of elevation.

What’s actually being measured?

Earth’s magnetic field isn’t uniform. The crust contains iron-bearing structures that create a patchwork of local anomalies. Traditional compasses only give heading; they don’t use the subtle spatial fingerprint needed for precise positioning.

High-end magnetometers—including quantum-enhanced approaches—can measure magnetic field changes with far greater sensitivity. That sensitivity makes “magnetic fingerprints” usable for navigation.

Why this isn’t a clean GPS replacement

Magnetic navigation has a built-in contradiction:

- The variation in Earth’s magnetic field is what makes it useful for geolocation.

- That same variation makes performance highly location-dependent.

Some regions are magnetically rich (distinctive patterns). Others are magnetically bland (hard to disambiguate). Add platform interference, altitude, maneuvers, and environmental noise, and you get a system whose accuracy can swing dramatically.

That’s why the best framing is: Magnetic navigation is a component in a resilient PNT architecture, not a single-system substitute.

The real breakthrough: navigation that knows its own limits

The direct answer: The hardest part of magnetic navigation is assurance—producing a reliable confidence bound on position error in real time.

The Defense One report highlights an issue many programs underestimate: legacy performance metrics can mislead you when you move from well-instrumented test conditions to messy operational reality.

In scripted testing, you can do things like:

- Fly a specially outfitted aircraft

- Put the magnetometer in a “clean” location on the airframe

- Collect dense data to build a well-sampled magnetic map

Then you get “tens of meters” accuracy and everyone’s happy.

But operational deployments don’t look like that:

- Different airframes, wiring, payloads, and power states change electromagnetic noise

- Flight profiles and altitudes vary

- Maps may be incomplete or stale

- The environment can produce ambiguous matches

SandboxAQ’s approach, as described, emphasizes computing a statistic that reflects how often the error stays within knowable bounds—think of it as a “position cloudiness” score rather than a single-point estimate.

A navigation solution isn’t usable unless it can say, in plain terms: “Here’s where I think I am—and here’s how wrong I could be.”

This is where AI becomes operationally meaningful. A well-designed model can learn patterns of degradation, detect out-of-family behavior, and drive a confidence-aware output that downstream autonomy can use.

Why confidence beats raw accuracy

If you’re designing autonomous or semi-autonomous behaviors (UAS routing, weapons release constraints, formation keeping, rendezvous, or deconfliction), you often need predictable error bounds more than occasional peak accuracy.

A system that is “sometimes excellent, sometimes silently terrible” is worse than a system that is “consistently moderate, but honest about uncertainty.”

How this fits into AI-enabled autonomy and mission planning

The direct answer: Quantum sensing strengthens autonomy by providing an additional, non-RF navigation signal that AI can fuse and validate against other sensors.

GPS denial hits more than navigation. It hits:

- Targeting and effects (weapon guidance, cueing, geolocation)

- C2 and mission timing (synchronization, time-on-target)

- ISR workflows (precise sensor pointing and geotagging)

- Swarming and teaming (relative positioning and deconfliction)

Magnetic navigation supports these missions in two ways:

- As a GPS-independent absolute reference (when maps and conditions support it)

- As a cross-check to detect spoofing or drift in other sources

Practical architecture: “PNT diversity” instead of “PNT replacement”

The most credible near-term pattern is a fusion stack such as:

- IMU / inertial navigation for short-term stability

- Magnetic navigation to reduce drift when magnetic signature is strong

- Barometric + radar altimetry to constrain vertical error

- Vision/terrain methods where available

- Signals of opportunity (when policy and operational constraints allow)

AI’s job is to fuse these inputs, detect anomalies, and dynamically weight sensors based on context.

What mission planners should ask for (and what to avoid)

If you’re evaluating GPS alternatives for contested operations, push for answers to these questions:

- Integrity: How does the system detect it’s wrong? What’s the false alarm rate?

- Bounded error: Does it output credible confidence intervals (not just point error after the flight)?

- Generalization: How does it perform across airframes, payload configurations, and power states?

- Map dependency: What happens in poorly mapped regions or over water?

- Operational cues: How is uncertainty presented to operators and autonomy logic?

Avoid programs that only report “best-case accuracy” without explaining when and why performance collapses.

Deployment reality: what will slow this down (and how to speed it up)

The direct answer: Fielding will be limited by calibration, mapping, and certification—not by a lack of interest.

The Pentagon’s expansion of testing through DIU is a signal that stakeholders want to move from demos to operational learning. That’s smart. It also exposes friction points you should plan for.

1) Electromagnetic hygiene on real aircraft

Magnetometers are sensitive. Real aircraft are noisy.

If the sensor’s “view” is polluted by onboard sources, you’re not measuring Earth—you’re measuring your own platform. Fixing this may require:

- Better sensor placement and shielding

- Characterizing emissions across power states

- Software compensation models that adapt over time

2) Magnetic maps: coverage, resolution, and update cycles

Magnetic navigation is only as good as its reference data. High-resolution maps aren’t universal, and collecting them at scale can be expensive.

A realistic approach is tiered:

- High-resolution mapping for priority theaters and corridors

- Accepting degraded performance elsewhere—but with honest confidence outputs

- Using operational flights to incrementally improve maps where feasible

3) Certification and trust for safety-of-flight

Military adoption still has to satisfy safety, reliability, and human factors standards.

The fastest path isn’t “declare it safe.” It’s:

- Start as a decision aid (advisory mode)

- Move to blended navigation (limited authority)

- Earn primary/alternate status through evidence across conditions

That progression pairs naturally with DIU-style field experimentation.

What leaders should do next (actionable guidance)

The direct answer: Treat quantum magnetic navigation as a resilience layer, fund the assurance work, and build it into autonomy requirements now.

Here’s what works in practice:

-

Write requirements around integrity, not hype.

- Demand real-time confidence bounds and fault detection performance.

-

Bake GPS-denied navigation into autonomy TTPs and test events.

- If autonomy is part of your roadmap, navigation assurance is not optional.

-

Invest in data strategy early.

- Mapping plans, data rights, update cadence, and cross-platform transfer matter as much as sensor specs.

-

Plan for multi-sensor fusion from day one.

- The winning systems will be those that combine inertial, magnetic, and other cues with robust AI.

-

Operationalize “trust displays.”

- Operators and mission systems need clear indicators: good / degraded / unusable, plus what fallback logic kicks in.

If you’re building or buying AI for defense, this is the type of problem that separates prototypes from capabilities: confidence-aware systems that behave responsibly when the world gets adversarial.

Where this goes in 2026: autonomy will force the issue

The direct answer: As autonomous platforms proliferate, the demand for GPS alternatives with verifiable integrity will spike—because autonomy can’t “improvise” when its position estimate is untrustworthy.

I expect 2026 program conversations to shift from “Which sensor is most accurate?” to “Which navigation stack fails gracefully?” That’s the right shift. The Pentagon’s interest in quantum sensing isn’t just a bet on physics—it’s a bet on building AI-enabled navigation that can explain itself, bound its errors, and keep operating when GPS is contested.

If you’re responsible for autonomy, mission assurance, or next-gen PNT, the practical question to ask your team this quarter is simple: When GPS lies, how will our system know—and what will it do next?