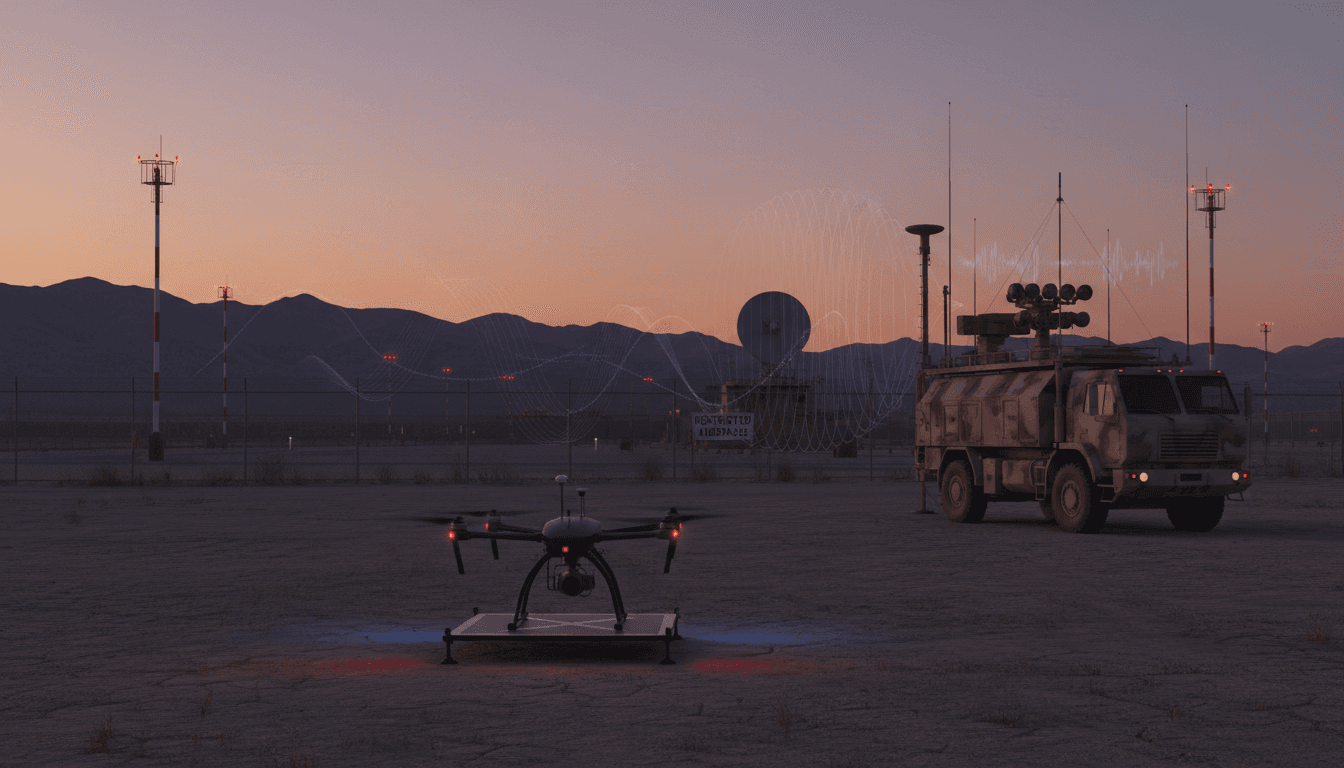

Special operators need more GPS-denied ranges. It’s also the fastest way to harden AI drones and EW systems with real-world data and testing.

GPS-Denied Training Ranges for AI Drones & EW

Ten.

That’s how many public FAA advisories for pending GPS interruptions appeared in 2025—an oddly small number when you consider how much modern warfare now assumes GPS will be jammed, spoofed, or simply unavailable.

U.S. special operations trainers are pushing to expand the places where troops can practice electronic warfare (EW) and drone operations under real signal interference. On paper, it sounds like a niche range-management issue. In reality, it’s one of the biggest bottlenecks in AI in defense and national security right now: you can’t build trustworthy autonomy, resilient navigation, or AI-enabled mission systems if your training environment is “clean” while the real world is hostile.

Here’s the stance I’ll take: the U.S. won’t field reliable AI-enabled drones at scale without more GPS-denied, EW-rich test space—plus the data pipelines and safety frameworks that make those ranges usable.

Why expanding EW ranges is really an AI readiness issue

Expanded EW ranges matter because AI systems learn from what you can safely and repeatedly expose them to. When spectrum interference and GPS denial are rare events in training, autonomy becomes a demo feature instead of an operational capability.

The RSS source highlights a practical constraint: the U.S. has only a limited number of places where cellular and GPS jamming can occur regularly (with frequent references to major test ranges). Special operators are asking regulators to widen that aperture because drone warfare has become inseparable from electronic warfare. That’s not just a tactical truth—it’s an AI engineering truth.

Three AI impacts flow directly from this range shortage:

- Not enough “hostile environment” data: AI-enabled perception, navigation, and signal classification need datasets that reflect contested conditions—multipath, interference, spoofing attempts, intermittent comms, and degraded sensors.

- Under-tested autonomy: When comms drop, autonomy has to pick up the slack. If autonomy is never exercised under stress, you’re shipping risk.

- Slow iteration cycles: Units and developers can’t iterate weekly if range approvals take months and must avoid disrupting civilian infrastructure.

This matters because in 2025, the most valuable “software feature” in many drones isn’t speed or payload—it’s graceful degradation: how the system behaves when GPS and links fail.

The Ukraine lesson: autonomy rises as jamming gets louder

The article points to battlefield adaptation: in Ukraine, jamming pressure has pushed drones toward fiber-optic control and more autonomous behaviors, reducing dependence on jammable links.

That’s the broader trend special operations is responding to:

- EW intensity is increasing (more emitters, more power, more sophistication)

- Drones are being redesigned for low/no-link operation

- Target recognition is shifting toward onboard AI (shape/size cues, local classification)

A practical takeaway: EW isn’t just an “attack” domain anymore. It’s the environment your AI must survive inside.

The real bottleneck: spectrum rules built for peacetime certainty

The key friction is simple: the U.S. protects civilian GPS and communications reliability, and for good reason. But the process that safeguards the public also makes realistic military training hard to schedule and hard to scale.

Special operations leaders are essentially saying: we need more places—at least temporarily—where we can create the conditions troops will face in conflict. That means working with aviation and communications regulators and accepting that the conversation will be uncomfortable.

The problem isn’t that regulators are “wrong.” The problem is that the operating assumption behind many constraints—that large-scale GPS disruption is an edge case—doesn’t match the operational reality anymore.

Two truths that can both be right

If you’re building policy for EW training ranges, you have to hold two truths at once:

- Truth #1: GPS is critical national infrastructure. Disruptions have safety and economic impact.

- Truth #2: GPS disruption is a normal condition in modern combat. Training without it creates a combat-credibility gap.

The bridge between those truths is not “jam less.” It’s jam smarter.

What “AI-grade” EW and drone training should look like

The best training ranges in 2026 won’t just be larger. They’ll be instrumented, repeatable, and data-rich.

If you want resilient AI-enabled drones and mission systems, ranges should support four capabilities at minimum.

1) Controlled GPS denial and spoofing, not just jamming

Jamming tests whether the receiver can function in noise. Spoofing tests whether the system can detect deception.

An AI-grade range should enable:

- Variable-power GPS denial zones

- Spoofing scenarios with known “ground truth”

- Timing/position corruption that’s measurable and replayable

The reason this is AI-relevant: spoof detection and navigation integrity are classification problems. They improve dramatically when you can label data from many scenarios.

2) RF chaos that reflects real cities, not empty desert physics

Many systems work fine in open terrain and fail in clutter: multipath reflections, dense emitters, and intermittent line-of-sight.

Ranges don’t need to be urban to simulate urban RF. They need:

- Emulated cellular/Wi-Fi activity

- Multi-emitter interference (friendly + adversary)

- Logging that ties RF conditions to drone performance outcomes

If you can’t measure the spectrum, you can’t improve performance.

3) Full kill chain rehearsal: sense → decide → act (under EW)

EW training often focuses on “can we jam?” Drone training often focuses on “can we fly?” AI-enabled warfare requires both—and the glue is decision-making under uncertainty.

A serious scenario tests:

- Target detection under degraded sensors

- Human-machine teaming when the link is intermittent

- Autonomous return-to-base, reroute, or mission abort logic

This is where special operations needs are a bellwether. If special operators need it for high-risk missions, conventional forces will need it at scale.

4) Rapid modification loops for field-built drones

The source describes a very real need: teams want to build, modify, and validate drones quickly—sometimes away from their home station—because the local range environment can’t support the right EW conditions.

For AI and autonomy, iteration speed matters. The loop should be:

- Modify payload, firmware, or autonomy behavior

- Run an EW-contested mission profile

- Collect logs (RF, navigation, video, control inputs)

- Update models/rules

- Re-test within days—not quarters

A range that can’t support fast loops becomes a museum.

How expanded ranges accelerate AI innovation (and where to be careful)

If you expand EW training space, you get an innovation dividend—but you also inherit new risks.

The innovation dividend: better models, better operators, better trust

Expanded ranges help in three specific ways:

- Data volume and diversity increase: better training sets for perception and navigation resilience.

- Evaluation improves: you can quantify mission success rates under specific EW profiles.

- Operator intuition grows: troops learn what “normal failure” looks like, so they don’t panic—or over-trust—automation.

This is especially relevant to AI in defense and national security because trust is earned through exposure to failure modes, not through perfect demos.

The risks: spillover, secrecy, and “training scars”

Policy and engineering teams should plan for:

- Spillover effects: interference bleeding beyond intended boundaries.

- Signature leakage: adversaries learning tactics or emissions patterns.

- Training scars: teams adapting to range-specific quirks that don’t generalize.

The fix isn’t to avoid training. It’s to build governance and instrumentation so outcomes are controlled, logged, and auditable.

“If the training environment is too clean, your AI will learn habits that get people hurt.”

Practical next steps for defense teams and partners

If you’re in government, an integrator, or a company supporting autonomy and EW, there are concrete moves you can make now—without waiting for a perfect national plan.

A range-expansion checklist (what to ask for)

When evaluating a proposed EW/drone training expansion, ask for:

- Defined denial volumes (where disruption is allowed, by time and geography)

- Scenario library (repeatable EW profiles: light, medium, heavy, spoof)

- Data rights and pipelines (who collects logs, how they’re labeled, where they live)

- Safety cases (how aviation and nearby services are protected)

- After-action metrics (mission success rate, link-loss recovery time, nav error)

If you can’t answer those questions, the site might be a “range” but it’s not an AI development asset.

Build a joint data approach early

One hard truth: every program hoarding its own EW and drone data slows everyone down. The most effective model is shared infrastructure with role-based access:

- Common telemetry formats

- Standard red-team EW profiles

- Shared “ground truth” labeling methods

- Clear handling rules for sensitive emissions data

That’s how you turn training events into a compounding advantage.

Where this fits in the AI in Defense & National Security series

Across this series, a pattern keeps repeating: AI capability isn’t limited by algorithms first. It’s limited by environments, data, and operational validation.

Expanded electronic warfare and drone training ranges are the physical counterpart to AI-ready networks and mission systems. They’re where autonomy earns credibility—where models face interference, deception, and uncertainty, and where operators learn how to manage AI under stress.

If you’re responsible for autonomy, EW, or special operations readiness, the question isn’t whether GPS-denied training is needed. The question is how fast you can create enough safe, instrumented space to learn at the pace of real conflict.

If you want help designing an AI-grade test and evaluation approach for EW-contested drones—data collection, metrics, safety cases, and model validation—this is the right time to build that plan for 2026 programs and budgets. What would your system do on its worst day, not its best demo?