An F-22 pilot just commanded a drone wingman in flight. Here’s what it means for AI-enabled autonomy, manned-unmanned teaming, and CCA programs.

F-22 Pilot Controls a Drone Wingman: What’s Next

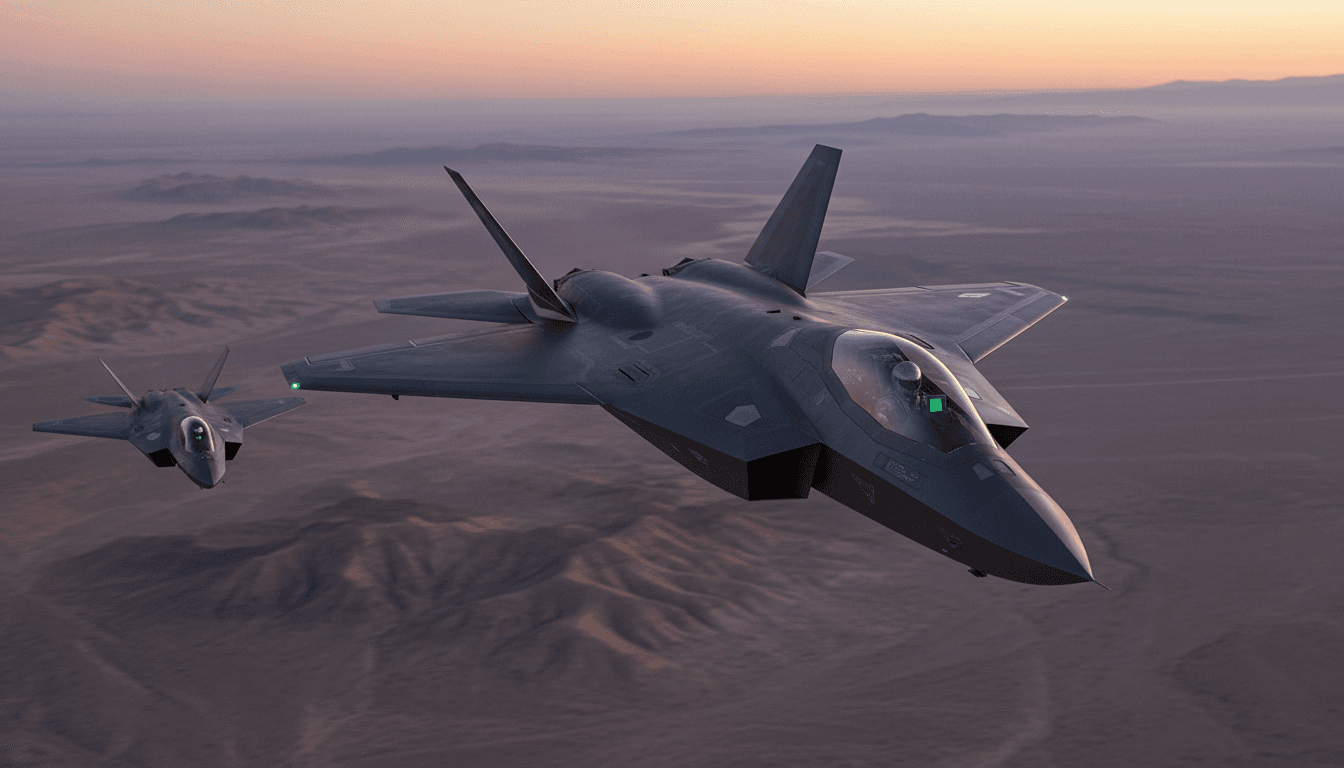

A single-seat F-22 flying over Nevada just did something the Air Force has been promising for years: the pilot actively commanded a drone wingman during flight. Not in a simulator. Not in a lab. In the air.

That one detail—the human pilot using an in-cockpit interface to direct an uncrewed jet—matters more than the usual “future of airpower” talk. It’s the difference between a concept and an operational pattern: crewed fighters acting as on-scene commanders for autonomous aircraft that can scout, jam, decoy, or strike.

For this installment of our AI in Defense & National Security series, the point isn’t to cheer a demo flight. The point is to understand what it signals about where AI-enabled autonomous systems are headed, what has to be true for this to scale, and what defense leaders and industry teams should be building (and buying) next.

The real milestone: cockpit control of an uncrewed jet

The milestone isn’t “a drone flew near a fighter.” It’s that an F-22 pilot reportedly used a tablet interface for command and control of a General Atomics MQ‑20 Avenger during an Oct. 21 test flight on the Nevada Test and Training Range.

That sounds straightforward until you unpack it. Manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T) has existed for years in other forms—especially in ISR workflows. But fighter-to-uncrewed jet control in a contested, time-compressed environment is a different problem.

Why this is harder than it looks

A fighter pilot’s bandwidth is already saturated: sensors, comms, threats, fuel, mission timing, weapons, deconfliction, and rules of engagement. Adding “drone manager” only works if:

- The interface is fast (few taps, minimal menus)

- The drone can execute intent-based tasks (not joystick-level piloting)

- Communications are resilient enough for contested conditions

- Autonomy fills the gaps when links degrade

That last point is where the AI in defense story becomes real. If the drone requires constant babysitting, it’s a liability. If it can interpret commander intent and behave predictably, it becomes a force multiplier.

The open-architecture signal

The demo involved Lockheed Martin and L3Harris working with General Atomics, highlighting government-owned, non-proprietary communications and open radio architectures. That’s not a throwaway detail.

Air forces get trapped when autonomy, datalinks, mission systems, and payload control are locked behind proprietary interfaces. Open architecture isn’t a procurement slogan here—it’s the only way CCAs scale across platforms and vendors.

AI-enabled “drone wingmen” are about tactics, not toys

The fastest way to misunderstand collaborative combat aircraft is to frame them as “extra airplanes.” The better framing is: CCA is a tactics engine.

A piloted fighter plus one or more autonomous wingmen lets you distribute risk and workload in ways traditional formations can’t.

What a drone wingman actually does

In practical mission terms, a CCA-type wingman can be tasked to:

- Extend sensor coverage forward of the crewed aircraft

- Act as a decoy to pull enemy radar/IR attention

- Carry jammers or electronic support payloads

- Hold additional weapons (or act as a launch platform)

- Probe air defenses to map threat emitters

- Provide communications relay when terrain or jamming breaks the mesh

The F-22 demo matters because it’s focused on the most operationally stressful use case: a high-performance fighter pilot directing effects in real time.

Autonomy isn’t “no human involved”

A lot of public conversation gets stuck on whether systems are fully autonomous. Real-world defense programs tend to live in a more disciplined middle ground:

- Human-in-the-loop: human approves actions

- Human-on-the-loop: human supervises and can veto

- Human-out-of-the-loop: system acts without oversight (rare and politically sensitive)

For air combat applications, the near-term sweet spot is human-on-the-loop paired with strong constraints and verification. You want autonomy for navigation, formation keeping, sensor management, and route replanning—but you want humans setting intent and controlling lethal authority.

The F-22 is becoming the “threshold platform” for CCA integration

The Air Force has been clear in planning documents: the F-22 is the threshold platform for CCA integration, with CCAs later supporting next-generation fighters like the F-47.

That’s a big deal for two reasons:

- F-22 relevance into the 2030s/2040s. Modernization isn’t just about keeping the jet viable—it’s about making it a node that can command a team.

- Risk reduction before the fleet arrives. If you can prove cockpit workflows, datalink behaviors, and autonomy concepts on surrogate aircraft now, CCA fielding becomes less of a cliff.

Why a tablet in the cockpit is more than a UI choice

The interface approach—tablet-like command and control—signals a shift in philosophy: pilots won’t “fly” wingmen; they’ll assign tasks.

Think of it like this: the pilot shouldn’t tell the drone how to do something. The pilot should tell it what outcome to create.

Examples of intent-based tasking that autonomy can support:

- “Go to waypoint set B, stay low observable, scan sector 30–60 degrees.”

- “Shadow this track and maintain offset formation at 5–8 miles.”

- “Hold weapons; follow my commit criteria; transmit threat updates.”

The AI work happens underneath: route planning, deconfliction, sensor cueing, classification confidence, link management, and fail-safe behavior.

What has to be true for this to work in real combat

A demo flight proves feasibility. Combat utility requires engineering discipline across autonomy, networks, and trust.

1) Contested comms must be assumed, not treated as an edge case

A collaborative combat aircraft that needs pristine connectivity will fail in the very scenario it’s built for. The autonomy stack must support:

- Graceful degradation: reduced features, not catastrophic failure

- Local decision-making: maintain formation, avoid threats, return-to-base logic

- Store-and-forward behaviors: relay data when connectivity returns

This is where AI-enabled decision support becomes operationally meaningful: autonomy isn’t about replacing people; it’s about keeping the mission coherent when information is incomplete.

2) “Trust” is a technical requirement

Trust isn’t vibes. It’s measurable behavior.

Operators trust systems when they are:

- Predictable: they do what they say they’ll do

- Auditable: they can explain state, constraints, and intent

- Recoverable: they fail safely and return control cleanly

For CCA, one of the most underappreciated needs is transparent autonomy: pilots need quick answers to “What are you doing?” and “What will you do next?” without reading a dissertation.

3) Interoperability beats vendor lock

The demo emphasized open radio architectures and government-owned comms capabilities. That’s the right direction, and I’ll take a stance here: vendor lock is a strategic vulnerability.

If CCAs become central to air dominance, the U.S. can’t afford a future where:

- one prime controls the only compatible datalink,

- autonomy updates require proprietary toolchains,

- mission apps can’t be swapped quickly.

The procurement winners won’t just be the companies with fast prototypes. They’ll be the ones who can prove modular mission autonomy, interface standards, and upgradeable software pipelines.

“People also ask” questions defense teams should be ready to answer

Will drone wingmen replace fighter pilots?

No. Drone wingmen shift pilots from “platform operators” to mission commanders. The human role becomes more strategic: intent, judgment, escalation control, and coordination.

How many wingmen can one pilot control?

Near term, expect one or two to be realistic in high-threat scenarios. The limiting factor is not flight control—it’s cognitive load, communications management, and how well autonomy converts intent into action.

What’s the biggest program risk?

It’s not airframes. It’s software integration at scale: autonomy verification, cyber-hardening, mission-system interoperability, and the operational testing needed to prove trust under stress.

What this means for buyers, builders, and integrators

If you’re leading programs in AI in defense & national security, this F-22-to-drone control demo is a practical roadmap for where investment should go.

For defense acquisition and capability leaders

Prioritize requirements that force maturity where it counts:

- Intent-based tasking (not manual remote piloting)

- Degraded-comm operations as a baseline

- Government-owned interface standards for comms and control

- Operational test realism: EW, jamming, confusing tracks, compressed timelines

For industry teams building autonomy, comms, and mission systems

Differentiation will come from execution details:

- Autonomy that can hold constraints (ROE, geofencing, target ID rules)

- Pilot UI that reduces actions to a few meaningful commands

- Radios and datalinks that support multi-node resilience

- Tooling for rapid updates without breaking safety cases

For organizations thinking about deployment and sustainment

Software-defined combat systems don’t succeed on first delivery. They succeed on iteration.

That means:

- A pipeline for secure updates

- Data collection and labeling workflows from real sorties

- Test harnesses that recreate edge cases at scale

- Cyber defense integrated into avionics and autonomy from day one

Where this goes next

The Air Force’s collaborative combat aircraft path is getting real faster than most organizations can absorb. An F-22 pilot commanding an uncrewed jet in flight is a small public window into a bigger shift: air combat is moving toward human-machine teams where AI manages complexity and humans manage intent and authority.

If you’re evaluating AI-enabled autonomous systems—whether for aviation, ISR, electronic warfare, or mission planning—the right question isn’t “Can it fly?” It’s: Can it be trusted to create effects under pressure when the network is breaking and the timeline is collapsing?

If you’re building toward that standard and want to pressure-test your architecture, autonomy approach, or integration plan, this is the moment to do it—before CCAs move from experiments to expectations.