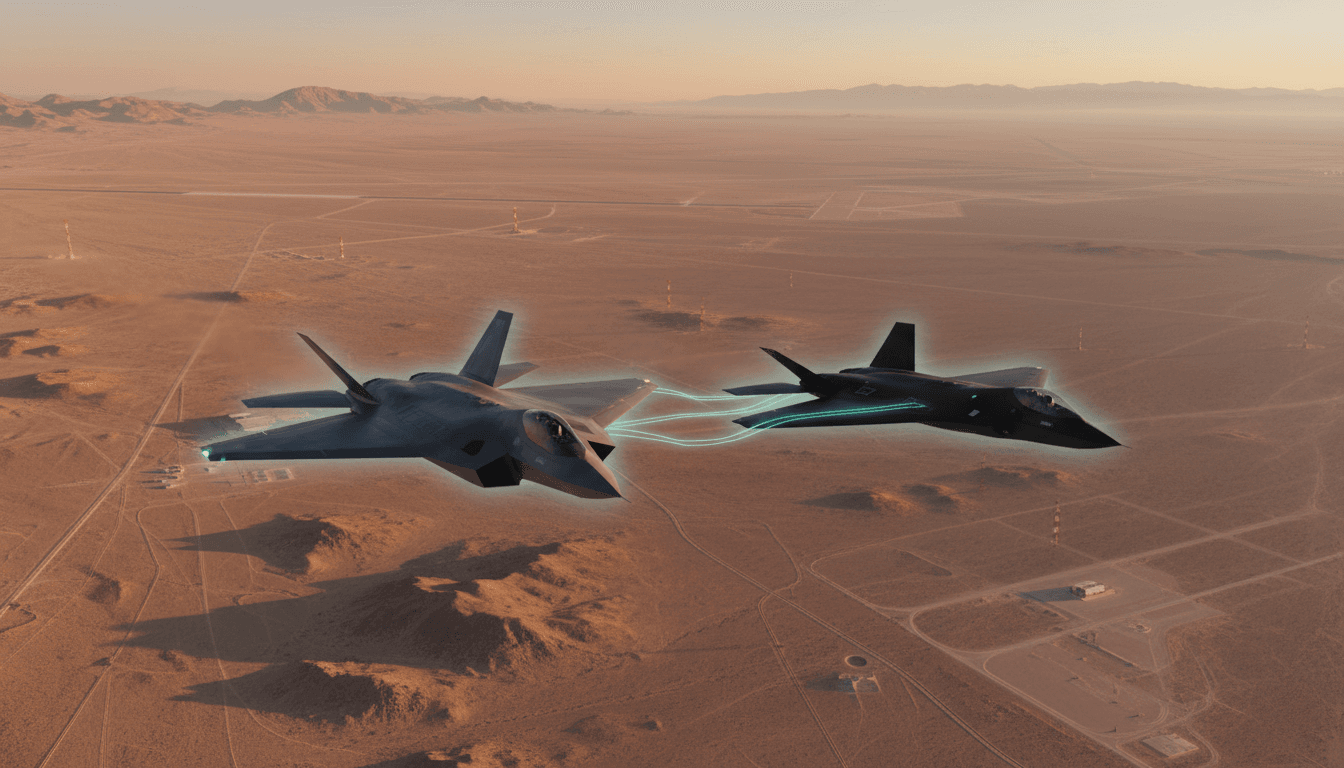

An F-22 pilot controlled a drone wingman in flight. Here’s what it means for AI in air combat, CCA programs, and contested operations.

F-22 Drone Wingman Test: What It Means for AI Combat

A single-seat F-22 pilot just used a tablet in flight to command and control an uncrewed jet—the MQ-20 Avenger—over a Nevada test range. That’s not a concept video or a lab sim. It’s an operationally relevant milestone: a human making real-time decisions while an AI-enabled aircraft executes as a “wingman.”

Most people hear “drone wingman” and picture science fiction autonomy. The reality is more practical—and more interesting. This matters because air combat is running into two hard limits at once: pilot workload and platform capacity. You can’t keep adding sensors, weapons, and mission tasks to one cockpit and expect performance to scale. Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) is the Air Force’s way of scaling combat power by pairing crewed fighters with uncrewed teammates.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, where we track what’s moving from theory to fieldable capability. The F-22-to-drone linkup is one of those moments.

What actually happened: the F-22-to-MQ-20 linkup

The key point: an F-22 pilot controlled a jet-powered drone during a live flight using an intuitive cockpit interface. According to the details released publicly, the demonstration occurred on Oct. 21 at the Nevada Test and Training Range and was announced in mid-November. General Atomics (MQ-20 manufacturer) worked with Lockheed Martin (F-22 prime) and L3Harris (datalinks and software radios).

Three specifics make this more than a headline:

- “In-flight command and control” implies the pilot wasn’t just receiving sensor video; they were issuing tasking to the uncrewed aircraft.

- The companies emphasized non-proprietary, government-owned communications capabilities, a not-so-subtle signal about interoperability and future scaling.

- General Atomics positioned the MQ-20 as a CCA surrogate because it already exists as a jet-powered uncrewed platform that can be “tricked out” with autonomy software for experimentation.

Here’s the sentence I’d want decision-makers to sit with: CCA isn’t waiting for a perfect drone—CCA is being proven using available aircraft plus mission autonomy software and the right datalinks.

Why this is a milestone for human-AI teaming in air combat

The key point: human-AI teaming is shifting from “autonomy demos” to “workload transfer” in real mission timelines.

A fighter pilot’s most precious resource isn’t fuel or missiles—it’s attention. Air combat is an attention management problem under lethal time pressure. When the pilot can offload tasks to an AI-enabled wingman, you get real operational benefits:

1) The cockpit stops being the bottleneck

If every new mission function must be mediated through one human’s hands and eyes, your combat capability hits a ceiling. A CCA changes the math:

- The pilot sets intent (search this sector, trail at this spacing, hold this line, jam this emitter)

- The uncrewed aircraft executes the details (navigation, formation keeping, sensor pointing, timing)

That’s where mission autonomy matters. Not “full autonomy,” but the kind that turns pilot commands into coordinated actions without step-by-step joystick control.

2) The unit of combat power becomes the team

In modern air warfare, what wins isn’t only platform performance; it’s the networked team’s kill chain speed—detect, identify, decide, and act. A crewed-uncrewed team can:

- Spread sensors across geometry (better detection and tracking)

- Create tactical dilemmas (multiple threats from multiple axes)

- Preserve the crewed fighter (push risk outward)

A useful way to say it: an AI wingman is a way to buy time—time to decide, time to reposition, time to survive.

3) “Simple and intuitive” interfaces are the hidden requirement

The companies emphasized cockpit usability. That’s not PR fluff. If the interface is clunky, pilots won’t use it in a fight.

A workable cockpit control experience generally needs:

- Intent-based commands (“screen left,” “sanitize sector,” “shadow track,” “hold fire”)

- Predictable autonomy behaviors (no surprises, no weird edge cases)

- Fast trust calibration (pilot sees why the AI did what it did)

AI in defense succeeds when it respects human limits. If you make the pilot manage a second aircraft like an RC hobby drone, the concept dies.

The strategic implications: range, mass, and survivability

The key point: drone wingmen are a force-structure answer to contested airspace, not a gadget.

The Air Force has been clear that CCAs are central to operating in “highly contested environments.” The uncrewed teammate approach supports three strategic needs that show up repeatedly in Indo-Pacific planning and high-end deterrence debates:

Mass without multiplying pilots

Training a fifth-generation fighter pilot takes years and substantial throughput capacity. CCAs offer a path to increasing the number of “combat aircraft in the formation” without a one-for-one increase in aviators.

That doesn’t remove people from the loop; it rebalances people toward supervision, intent, and judgment—where humans still outperform machines.

Extending reach and coverage

Even when a crewed fighter has excellent sensors, it can only be in one place at one time. A CCA can:

- Push sensing forward (see first)

- Act as decoys or escorts (force adversary emissions)

- Provide standoff effects (jamming, sensor fusion, weapons carriage)

In practice, that can translate into fewer risky penetrations by crewed jets—and more flexible tactics.

Survivability through distribution

A single high-value aircraft is a single high-value target. A formation that includes uncrewed aircraft distributes risk.

This isn’t only about sacrificing drones. It’s about presenting too many problems at once—forcing an adversary to reveal sensors, expend interceptors, or break their formation.

The technical hard parts (and why open architectures matter)

The key point: the limiting factors aren’t “can we build a drone,” but “can we communicate, coordinate, and secure the team under attack.”

The press materials highlighted open radio architectures and government-owned communications. That’s where programs live or die, especially at scale.

Resilient datalinks under electronic attack

Any real peer fight includes jamming, spoofing, cyber attempts, and kinetic attacks on nodes. So a crewed-uncrewed team needs:

- Graceful degradation (the CCA keeps executing safely if link quality drops)

- Multiple paths (alternate waveforms / radios / routing)

- Authentication and anti-spoofing (trustworthy command authority)

A drone wingman that requires a perfect link is a fair-weather friend.

Mission autonomy that’s bounded, testable, and certifiable

Defense autonomy can’t be a black box that only works “most of the time.” It has to be:

- Constrained by rules of engagement and safety envelopes

- Verifiable in test across expected edge cases

- Updatable without breaking certification every time software changes

The best autonomy is boring in the right way: predictable, auditable, and aligned with commander intent.

Interoperability so CCAs don’t become vendor islands

If each drone requires bespoke integration with each fighter, you’ll never scale. That’s why “non-proprietary” comms matters. It’s also why the Air Force’s push toward modular, open systems approaches keeps resurfacing.

There’s a blunt procurement truth here: interoperability is cheaper than reintegration, and reintegration is where timelines go to die.

“People also ask” questions (answered plainly)

Is the drone flying itself or being remotely piloted?

In these concepts, it’s both. The uncrewed aircraft flies and manages many functions autonomously, while a human provides high-level tasking and oversight. Think “supervised autonomy,” not joystick control.

Why use an F-22 for this instead of a newer platform?

Because the Air Force has identified the F-22 as a threshold platform for CCA integration—a way to field the concept with a premier air dominance fighter while next-generation aircraft mature.

Does this mean autonomous weapons release is next?

Weapons employment is the most sensitive step operationally, legally, and politically. The more immediate path is AI-enabled support: sensing, escort, jamming, decoying, and positioning—while humans retain final engagement authority.

What’s the biggest risk to the CCA concept?

Two risks stand out:

- Control under attack (jamming/spoofing/cyber)

- Human trust and workload (if the interface increases workload, pilots will reject it)

What defense leaders should do now (actionable takeaways)

The key point: the winners in AI-enabled air combat will be the organizations that operationalize testing, not just prototype aircraft.

If you’re in defense, national security, or the industrial base, here are practical moves that pay off in 2026–2028 program decisions:

- Treat human-machine interface (HMI) as a primary requirement. If it isn’t usable at G-load, it isn’t usable.

- Build for contested comms from day one. Plan for link loss, partial control, and degraded modes as normal operations.

- Standardize mission “verbs.” Create a shared command vocabulary across platforms (“screen,” “trail,” “sanitize,” “hold,” “jam,” “decoy”).

- Instrument everything. Autonomy without telemetry is religion. You need data to improve behaviors and certify updates.

- Design trust calibration features. Explanations, intent visualization, and clear autonomy states reduce pilot uncertainty.

Where this goes next: from demo to doctrine

The key point: the Air Force isn’t chasing a cool demo—it’s building the playbook for human-AI air combat.

The October flight matters because it links three realities into one formation: a fifth-generation fighter, a jet-powered uncrewed aircraft, and an interface simple enough to use while flying. That combination is exactly what future doctrine needs—because doctrine is built on what crews can actually do, not what slides promise.

Over the next two years, expect the center of gravity to shift from “can it fly” to “can it fight as a team”—under jamming, under deception, with real tactics and real constraints. The first CCA production design decision is expected in 2026, and the pressure to show credible, scalable integration will only increase.

If you’re tracking AI in defense and national security, this is one of the clearest signals yet that the era of human-AI teamed air combat is being shaped right now—test sortie by test sortie. The question isn’t whether CCAs will exist. It’s which organizations will prove they can field them securely, integrate them broadly, and make them usable for the people who have to fight with them.

If a pilot can command a drone wingman from an F-22 today, what should a four-ship plus CCAs be able to do by 2028—and what will your program need to be ready for that reality?