An F-22 pilot controlled an MQ-20 drone wingman in flight. Here’s what it means for AI-enabled autonomy, mission planning, and CCA integration.

F-22 Drone Wingman Test Shows AI in Air Combat

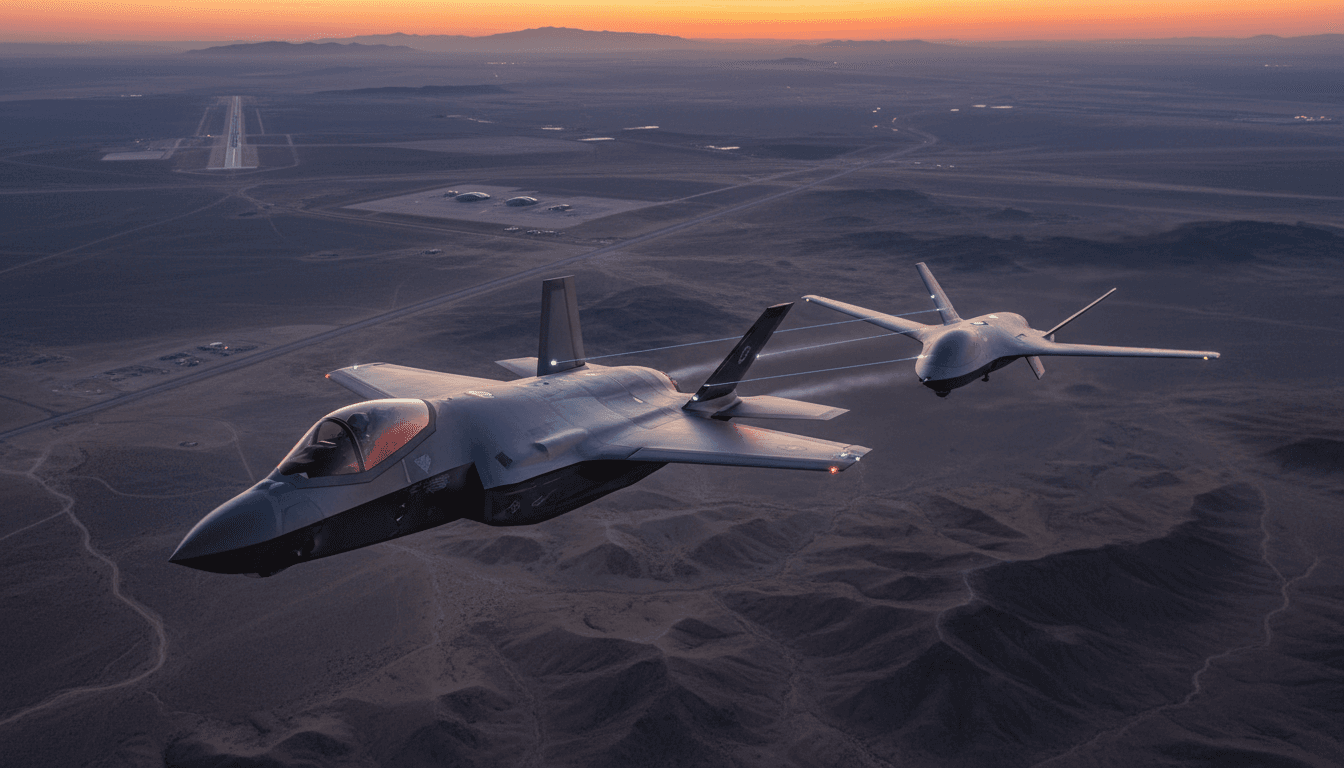

A single-seat F-22 piloted a second aircraft in flight—without adding another human to the formation. During an October test over the Nevada Test and Training Range, an F-22 pilot used a tablet interface to command and control an MQ-20 Avenger uncrewed jet. That detail matters: it’s not a lab demo, not a simulator vignette, and not a concept slide. It’s a crewed fighter managing an uncrewed wingman while airborne.

For the AI in Defense & National Security series, this is the kind of milestone worth pausing on. Not because a tablet in a cockpit is flashy, but because it signals the real shift underway: airpower is becoming a team sport—human decision-makers orchestrating AI-enabled autonomous systems at tactical speed.

The defense takeaway isn’t “fighters will be replaced by drones.” Most people who say that haven’t sat through the operational constraints—rules of engagement, comms denial, safety-of-flight, and the ugly reality of electronic warfare. The real takeaway is simpler and more useful: the Air Force is testing how to multiply combat mass while keeping pilots focused on judgment, not joystick work.

What actually happened in the F-22 drone wingman test

The key point: an F-22 pilot controlled an MQ-20 Avenger during a live flight using an in-cockpit tablet interface.

The test (reported publicly by the participating companies) brought together:

- General Atomics (MQ-20 Avenger and mission autonomy work)

- Lockheed Martin (F-22 builder; Skunk Works claims it orchestrated the event)

- L3Harris (data links and software-defined radios)

This matters for one reason that procurement and operations people will immediately recognize: interoperability. The messaging emphasized “non-proprietary, U.S. government-owned communications capabilities” and open radio architecture. That’s not marketing fluff. It’s a shot across the bow at closed ecosystems that trap programs into single-vendor upgrades.

Why the tablet interface is the real headline

Here’s what the tablet symbolizes: workload discipline.

A fighter pilot’s cognitive bandwidth is already consumed by:

- Threat detection and prioritization

- Weapon employment decisions

- Defensive maneuvers

- Formation management

- Comms and airspace coordination

If “controlling a drone wingman” requires constant attention, it’s dead on arrival. A workable concept needs simple intent-based controls—think: “go sanitize that sector,” “hold at this point,” “trail me at X spacing,” “target this emitter,” not “fly this heading at this altitude at this speed.”

That’s where AI in autonomous systems shows up in practical terms. The autonomy has to turn pilot intent into actions, handle routine flying, and surface exceptions.

Why this is a milestone for Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA)

The key point: CCA isn’t a single drone program; it’s a force design change—and the F-22 is being positioned as an early quarterback.

The Air Force has been clear that Collaborative Combat Aircraft will fly alongside crewed fighters, starting with platforms like the F-22 and later with the Next Generation Air Dominance family (including the emerging F-47 program).

If you want one sentence that captures what’s changing:

CCA is about scaling combat power per pilot, not scaling pilot headcount.

That’s attractive in December 2025 for three reasons that are hard to ignore:

- Pilot production and retention remain structurally difficult. Training pipelines are long, and experience can’t be rushed.

- Contested environments are getting denser. More sensors, more shooters, more jammers—more things that can kill you.

- Budgets are under pressure even when toplines rise. Modernization portfolios compete with readiness, personnel, and sustainment.

CCA creates a path to increase capacity—more sensors forward, more weapons in the formation, more decoys, more options—without pretending you can double the number of combat-ready fighter pilots quickly.

The MQ-20 Avenger as a “CCA surrogate” is smart for speed

General Atomics framed the MQ-20 as a “perfect CCA surrogate.” I agree with the logic even if you don’t buy the exact wording.

A surrogate lets you test the hardest parts early:

- Manned-unmanned teaming (MUM-T) workflows

- Data link performance and resilience

- Human-machine interface in the cockpit

- Autonomy behaviors under real flight conditions

Waiting for a production CCA air vehicle before doing that would be a self-inflicted delay.

The AI piece: autonomy that reduces workload (and risk)

The key point: AI’s value in a drone wingman isn’t “independent combat”; it’s decision support, exception handling, and mission execution under constraints.

When people hear “AI drone wingman,” they jump straight to weapons release. That’s the wrong first question. The first question is: what tasks can autonomy reliably do so a pilot can make better tactical decisions?

Three autonomy functions that matter immediately

-

Formation and deconfliction autonomy

- Keeping station, managing separation, and maintaining geometry while reacting to maneuvering

- This reduces the number of “babysitting” actions required by the pilot

-

Sensor management and track fusion

- Automating radar modes, EO/IR cueing, and emitter geolocation workflows

- The pilot gets better options faster, not more raw data

-

Threat response behaviors

- Pre-planned reactions to jamming, missile warning, or loss of link

- This is where “trusted autonomy” becomes real: what does the system do when things go wrong?

If you’re building a national security AI roadmap, these functions are the practical bridge between today’s assisted automation and tomorrow’s higher autonomy.

The reliability question nobody can dodge: comms denial

A drone wingman concept lives or dies on graceful degradation.

In a contested environment, you should assume:

- Intermittent links

- Spoofing attempts

- Congested spectrum

- Partial GPS denial

So the operationally credible model is not “pilot controls drone continuously.” It’s:

- The pilot sets intent and constraints

- The drone executes locally using onboard autonomy

- The system shares state and exceptions when connectivity allows

That’s also why the mention of government-owned, non-proprietary comms is so important. If your entire architecture assumes pristine connectivity, it’s not a combat architecture.

What this means for mission planning and battlefield efficiency

The key point: CCA changes mission planning from “platform assignment” to “team design.”

In traditional planning, you assign aircraft to roles: escorts, SEAD, strike, ISR, etc. In a mixed human-autonomous formation, planners start thinking in modular packages:

- One crewed fighter + two CCAs as sensor extenders and decoys

- One crewed fighter + one CCA carrying extra weapons for standoff shots

- Multiple CCAs ahead of the formation for electromagnetic mapping

That creates tangible battlefield efficiency gains:

- More persistence at the edge (uncrewed assets can accept higher risk)

- More shots per sortie (weapons trucks or missile carriers)

- Better survivability (distributed sensing, decoys, and alternate kill chains)

A realistic near-term use case: “scout, classify, cue”

The most credible early operational pattern isn’t autonomous dogfighting. It’s:

- CCA pushes forward to collect sensor and emitter data

- Autonomy helps classify what’s being seen

- The F-22 pilot gets a fused picture and chooses actions

That’s AI enhancing decision-making in exactly the way defense leaders say they want: faster understanding, fewer surprises, and less pilot workload.

The procurement lesson: open architecture is the point, not the footnote

The key point: who wins CCA matters, but the architecture matters more—because it determines upgrade speed for the next decade.

The article context notes General Atomics competing with Anduril, with production design decisions expected in 2026. Competition is good. But the strategic risk is ending up with:

- Multiple uncrewed aircraft

- Multiple proprietary control stacks

- Multiple closed data link approaches

That’s how you get slow integration, expensive upgrades, and fragmented training.

What works better—what I’ve seen succeed in other defense technology efforts—is treating the autonomy and comms layer like a platform-agnostic product:

- Standardized message formats

- Government-controlled interfaces

- Modular apps for autonomy behaviors

- Rapid flight-test loops that push software updates safely

If the Air Force gets that right, it won’t matter as much which airframe variant is in the first tranche. Software iteration speed will be the advantage.

“Trust” is earned through testing, not press releases

Manned-unmanned teaming will only scale if operators trust it. Trust comes from predictable behavior in edge cases:

- Lost link at the worst moment

- Conflicting cues from sensors

- Ambiguous targets under restrictive ROE

- Friendly aircraft unexpectedly entering the volume

So the smartest thing about this F-22/MQ-20 event is that it’s another data point in a trend: test early, test in the air, and prove integration step-by-step.

Practical questions leaders should ask now

The key point: the right questions are operational and architectural—not sci-fi.

If you’re a defense program leader, operator, or industry partner working on AI in national security, these are the questions worth putting on the agenda:

- What are the pilot’s top 5 “intent commands,” and how long do they take to execute?

- What happens when the link drops for 30 seconds? 5 minutes? the entire mission?

- Which autonomy behaviors are locked, and which can be updated via software?

- How do we validate and certify autonomy updates fast without lowering safety margins?

- What’s the minimum interoperability standard so CCAs can fly with multiple crewed platforms?

Those answers determine whether AI-enabled autonomous systems become a durable capability—or a set of one-off demos.

Where this goes next for AI in Defense & National Security

The key point: this F-22 drone wingman test is a preview of how AI will shape operational advantage: faster decisions, distributed sensing, and scalable combat mass.

Over the next 24 months, watch for progress in three areas:

- Human-machine interface maturity (less “control,” more “supervise”)

- Autonomy validation frameworks (repeatable, testable, auditable)

- Interoperable networks and radios designed for contested spectrum

If your organization is tracking AI in defense for strategy, investment, or capability planning, this is the signal: the Air Force is treating AI-enabled autonomous systems as a core ingredient of future air combat, not a niche experiment.

If you’re building, buying, or integrating these systems, the practical challenge is clear: make autonomy boringly reliable and cockpit control genuinely simple. That’s how you get adoption.

What mission would you redesign first if every fighter sortie could bring two autonomous wingmen—without adding more pilot workload?