Special operators need more EW training space. Pair expanded ranges with AI-driven AAR and scenario design to build real GPS-denied drone readiness.

AI-Ready EW Ranges: Fixing Drone Training’s Bottleneck

U.S. special operations trainers are running into a constraint that has nothing to do with operator motivation or tech ambition: there simply aren’t enough places in the United States where teams can train with realistic GPS and cellular jamming.

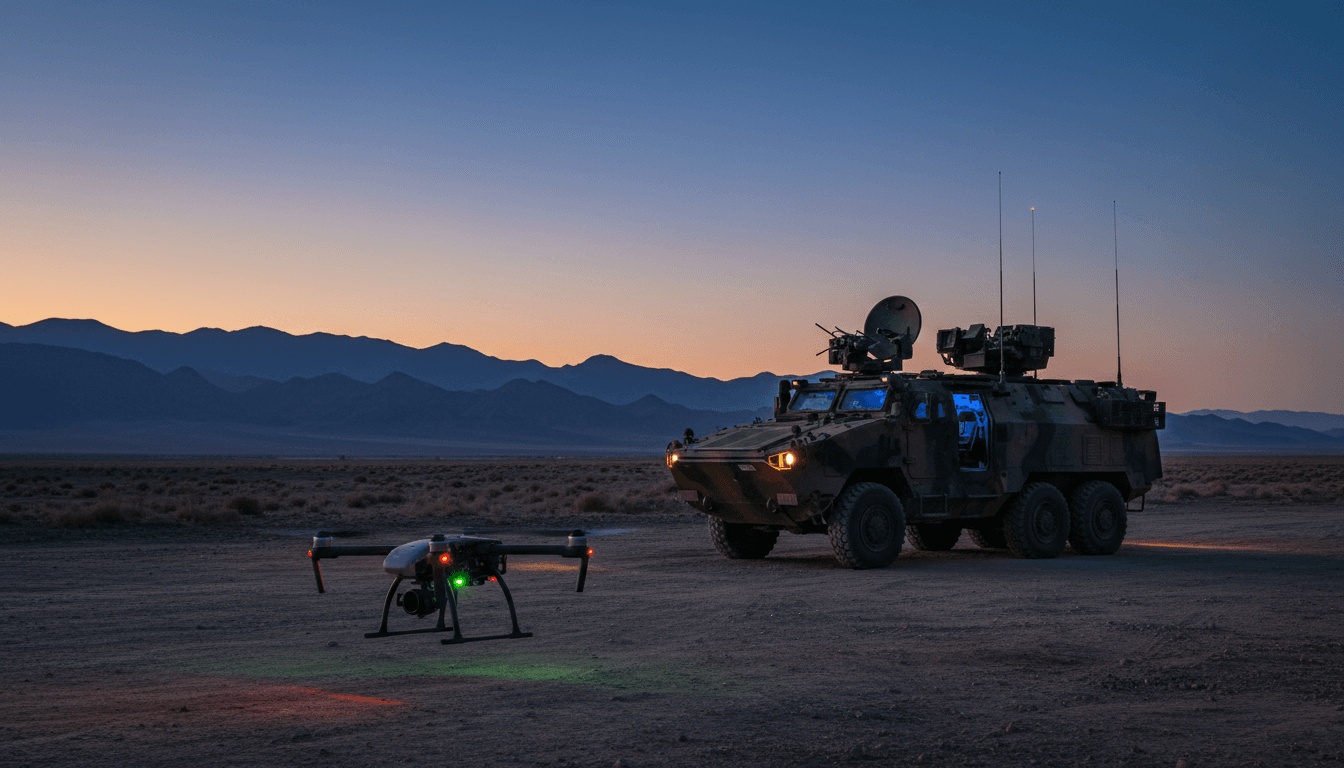

That sounds like a niche “range management” problem—until you map it to what’s happening in real conflicts right now. In Ukraine, electronic warfare (EW) is constant, GPS disruption is routine, and drones increasingly survive by switching to autonomy, alternative navigation, or non-RF control paths. When your adversary trains in a live-fire lab every day, “we can only do this at a couple of sites” stops being a scheduling headache and becomes a readiness gap.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, and I’ll take a clear stance: expanded EW ranges are necessary, but they’re not sufficient. The fastest way to turn more range access into real combat advantage is to pair it with AI-enabled training, test automation, and data pipelines that help special operators learn (and adapt) at the speed modern drone warfare demands.

The real bottleneck: you can’t train what you can’t legally simulate

Answer first: The biggest friction point in drone and EW readiness isn’t inventing new systems—it’s creating legal, repeatable, safe environments where jamming and spectrum effects are realistic.

Special operations leaders have been blunt about needing more places to train with GPS jammers and cellular disruption. They’re preparing request packets to coordinate with multiple federal regulators so training can occur in additional locations, even temporarily. That “temporary” detail matters: it signals a possible path forward—time-bound, controlled windows—but also highlights how far the U.S. training ecosystem is from the conditions operators will face.

Today, U.S. guidance and practice effectively concentrate regular GPS/cellular jamming activity into two primary locations: White Sands Missile Range (New Mexico) and the Nevada Test and Training Range. Other sites can be approved occasionally, but approvals are bureaucratic and the public notification process reflects a world where GPS denial was an exception rather than an expectation.

This matters because EW isn’t a single trick. It’s an environment. If your training only includes “jamming as an event,” you’ll build habits for a fight that doesn’t exist anymore.

Why this changed so fast

Answer first: Cheap drones plus pervasive jamming compressed the learning cycle of warfare from months to days.

What’s happening in Ukraine is forcing every modern military to confront an uncomfortable truth: the electromagnetic spectrum is now contested at small-unit scale. Teams can’t assume clean GPS, stable datalinks, or predictable RF conditions.

Several adaptations have accelerated that shift:

- Autonomy to reduce comms dependence: When drones can identify, track, or navigate with less external control, jamming loses some bite.

- Alternative control methods: Nontraditional control paths—including tethered or fiber-based approaches—reduce RF exposure.

- Faster field modification: Units change payloads, antennas, firmware, and tactics quickly. That demands training that’s equally iterative.

So when special operations training leaders ask for expanded jamming areas, they’re responding to a battlefield where EW is always on, not an “advanced block” you do once a year.

Expanded ranges are a policy win—AI is the readiness multiplier

Answer first: More EW range access creates opportunity; AI turns that opportunity into measurable readiness by structuring data, accelerating iteration, and personalizing training.

The source article describes new training and organizational moves—like a tactical signals intelligence and EW course pilot (15 students, July to October) and a dedicated robotics detachment (stood up in 2024), plus a specialist role for robot technicians. That’s the right direction: it recognizes that operators need EW literacy and robotic competence as baseline skills.

But here’s what most organizations underestimate: once you start training in realistic EW conditions, you generate a flood of telemetry—RF conditions, mission outcomes, control link performance, navigation error, operator inputs, near-misses, system failures. If you don’t handle that data well, you end up with “we trained hard” anecdotes instead of repeatable improvements.

Where AI fits, specifically

Answer first: AI should sit in the training loop as an analyst, coach, and range optimizer—without becoming a brittle dependency.

Practical AI applications that map directly to EW and drone training include:

-

Automated after-action review (AAR)

- In EW-heavy scenarios, humans miss patterns.

- AI can summarize mission phases, correlate jamming bursts with control dropouts, and flag “decision points” where outcomes changed.

-

Adaptive scenario generation

- If an operator consistently recovers from GPS denial but fails under intermittent datalink loss, the next run should target that weakness.

- AI can recommend scenario variations based on performance, not instructor gut feel.

-

Threat emulation at scale

- Realistic emulation means modeling how modern adversary jammers behave: power management, sweep strategies, reactive jamming, and deception.

- AI can help produce variability so trainees don’t memorize one “range signature.”

- Range scheduling and spectrum deconfliction

- Expanded test sites will still be constrained by safety, airspace, and spectrum rules.

- AI can optimize windows, predict interference footprints, and reduce the admin cost of running complex EW events.

A simple rule I use when advising teams: if training produces data, you need a model to make it useful. Otherwise you’re collecting “expensive exhaust.”

Training for GPS-denied ops: build redundancy, not heroics

Answer first: GPS-denied operations shouldn’t be treated as a specialty; they should be the default assumption, with layered navigation and resilient mission design.

The article highlights a key institutional problem: the U.S. historically treated GPS reliability as a given. That assumption shaped weapons, doctrine, and training infrastructure. Meanwhile, commercial reliance on GPS drove stricter controls around testing disruption. The result is a mismatch: the environment is contested, but the training ecosystem is optimized for a protected spectrum.

From an AI and autonomy perspective, the goal isn’t “make drones independent so jamming doesn’t matter.” The goal is graceful degradation—systems that keep delivering useful effects even as conditions worsen.

A practical resilience stack for drone training

Answer first: The most effective training stack layers autonomy, alternate navigation, and comms discipline.

Teams should train against a stack that includes:

- Navigation redundancy: GPS + inertial + vision-based navigation + terrain/reference matching where feasible.

- Comms redundancy: multiple bands, directional antennas, frequency agility, and strict emission control procedures.

- Autonomy guardrails: mission constraints, geofencing, and fail-safe behaviors that survive comms loss.

- Human-machine teaming: operators practicing when to intervene, when to let autonomy run, and how to recover safely.

AI supports this stack by testing edges quickly: it can help identify which redundancy actually improved mission completion rates under which jamming pattern.

What “expanded EW ranges” should look like in 2026

Answer first: The winning model is a network of smaller, instrumented, frequently available ranges—not a few mega-sites with rare access.

Congress has begun to acknowledge range constraints, including provisions oriented around linking testing sites and requiring EW features in certain future exercises. That’s movement, but the operational need is bigger than periodic exercises.

If I were designing the target end state for special operations and broader DoD users, I’d push for:

1) A distributed range network with consistent instrumentation

A credible network isn’t just geography; it’s standardized data capture:

- RF environment logging (spectrum snapshots, jammer power levels, timing)

- Drone telemetry capture (navigation error, link quality, autonomy mode transitions)

- Safety event tagging (geofence proximity, lost-link events, recovery outcomes)

The payoff: models trained at one site remain useful at another because the data schema is consistent.

2) “Jamming windows” designed like controlled burns

Instead of treating GPS denial as a rare, high-ceremony event, build an operating rhythm:

- predictable, time-bound windows

- automated notifications and internal approvals

- predefined safety corridors and fallback procedures

This reduces friction with regulators and normalizes the training environment operators actually need.

3) A digital twin of the range environment

Range digital twins aren’t sci-fi. They’re practical when you focus them:

- simulate RF propagation and interference

- replay events for AAR

- test scenario designs before turning on emitters

AI improves the twin by calibrating it to observed data so simulations stay aligned with reality.

“People also ask” (and what I tell teams)

Can AI replace live electronic warfare training?

No. AI can’t replace RF physics, airspace constraints, or the stress of operating in a degraded environment. What AI can do is compress learning cycles by making every run more informative and targeted.

Why not just train in simulation?

Simulation is essential, especially for rapid iteration and safety. But adversary EW behaviors, interference, multipath effects, and hardware quirks routinely break perfect sims. The right approach is blended: simulate early, validate often on instrumented ranges.

What’s the fastest win for SOCOM-adjacent programs?

Start with AI-assisted AAR and standardized data capture. You’ll get immediate value without waiting for new airspace approvals or large procurements.

What to do next (if you own training, ranges, or autonomy)

EW range expansion is finally getting serious attention. Good. The bigger question is whether the U.S. will use that access to create repeatable learning advantage.

If you’re building or buying capabilities in this space, I’d focus on three near-term steps:

- Define a common training data model for EW and drone events (telemetry, spectrum, scenario metadata).

- Pilot AI-enabled AAR on one course pipeline (robotics techs, tactical SIGINT/EW, or UAS operators) and measure improvement in mission success under jamming.

- Treat range operations as a software problem: scheduling, deconfliction, safety workflows, and scenario libraries should be versioned, auditable, and optimizable.

The next year will produce a lot of “more range capacity” headlines. The organizations that pair expanded access with AI-driven training loops will be the ones that show something rarer: faster adaptation than the threat.