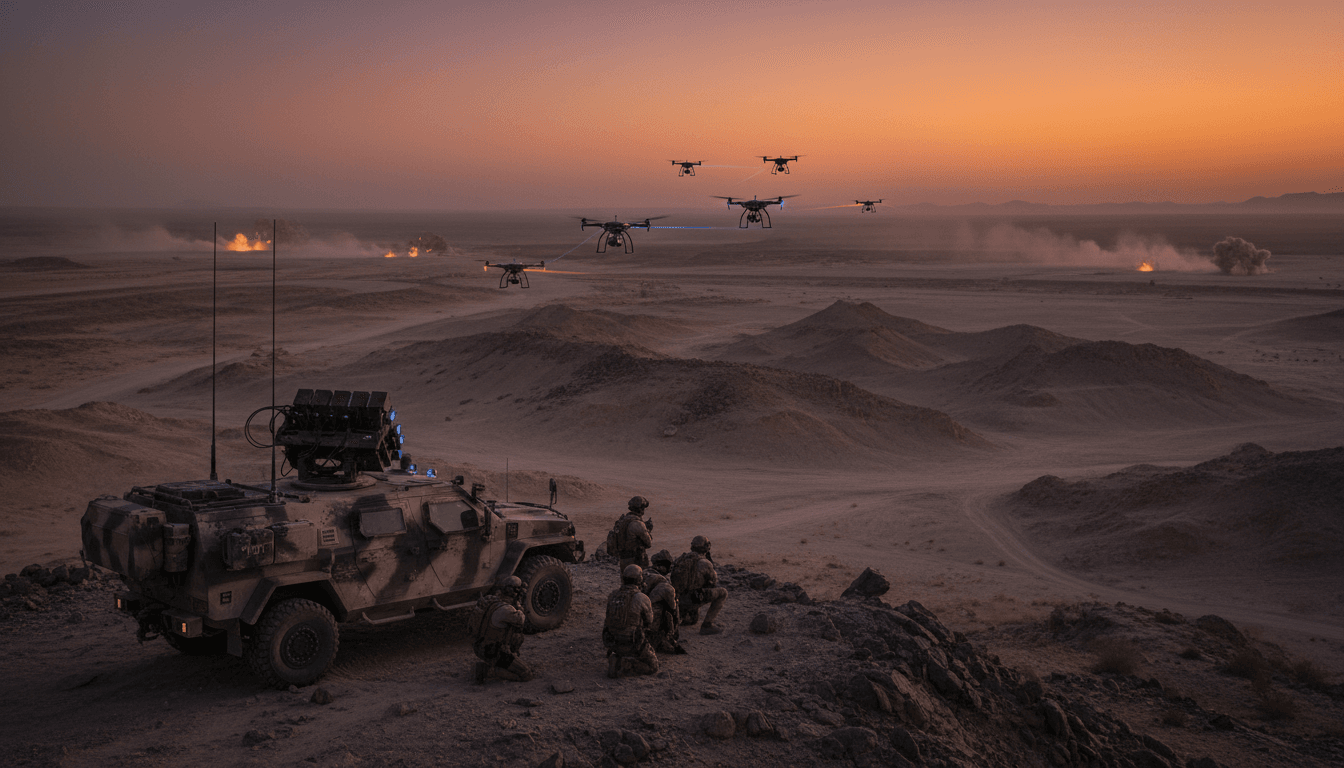

Special ops want expanded EW ranges to train AI-enabled drones under real jamming. Better range access is now a readiness and safety issue.

Why Special Ops Need AI-Realistic EW Drone Ranges

Only two U.S. sites routinely support GPS and cellular jamming for training and experimentation: White Sands Missile Range and the Nevada Test and Training Range. That’s not a trivia fact. It’s a readiness constraint.

Special operations trainers are now pushing federal regulators to expand where the U.S. military can simulate a modern battlefield—one saturated with electronic warfare (EW), cheap drones, spoofed navigation, and autonomous targeting. They’re right to push. Most companies (and frankly, plenty of program offices) still treat EW-denied operations as a niche scenario. Ukraine proved it’s the default.

This post is part of our AI in Defense & National Security series, and it’s a simple thesis: you can’t field AI-enabled drones and EW tools responsibly if you can’t test them under realistic interference at scale. The training range is becoming as strategic as the platform.

Expanded EW ranges are now a prerequisite for AI-ready forces

Answer first: Expanded EW and drone training ranges matter because AI-enabled autonomy, sensing, and targeting behave differently when GPS and communications are contested—and that difference can’t be validated in a lab.

In the Defense One reporting, leaders at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School describe an urgent need to train under heavier, more ubiquitous jamming—exactly the conditions driving real-world adaptation in Ukraine. A few years ago, it was plausible to treat GPS denial as an “edge case.” In 2025, it’s the planning assumption.

There’s a second point many miss: EW doesn’t just disrupt systems; it reshapes tactics. When the spectrum gets ugly, units change how they move, how long they transmit, how they cue sensors, and whether they trust machine recommendations. That human-machine loop is where AI either becomes an advantage—or a liability.

The uncomfortable truth about regulation and realism

Special operations leaders are preparing “uncomfortable discussions” with civil and federal authorities because U.S. law and safety policy rightly restrict jamming that could affect civilians. But the battlefield doesn’t share our regulatory boundaries.

If adversaries can iterate AI-enabled drones on active front lines—while U.S. forces iterate primarily inside narrow, carefully scheduled test windows—then our development tempo is being throttled by process, not engineering. That’s not a criticism of regulators; it’s a reality for planners.

Ukraine’s drone-EW loop shows where AI is heading

Answer first: Ukraine demonstrates that autonomy and counter-EW design are converging, pushing drones toward onboard AI, alternative navigation, and non-RF control paths.

The article highlights a pattern worth naming:

- As jamming intensifies, drones become less dependent on RF links.

- When GPS is unreliable, systems shift to inertial navigation, vision-based cues, map-matching, or human-in-the-loop corrections.

- When comms are jammed, drones shift to preplanned behaviors or higher onboard autonomy.

This is the real driver behind expanded ranges: you can’t teach operators—or validate systems—if the training environment doesn’t reproduce the failure modes.

Why fiber, autonomy, and onboard perception are showing up together

In contested environments, engineers are using multiple tactics at once:

- Tethered or fiber-controlled drones to bypass RF jamming.

- Autonomous “continue mission” behaviors when the link drops.

- Onboard perception (computer vision) to identify targets or landmarks.

That third point is the AI link. The moment a drone uses onboard perception to classify or track, it becomes sensitive to things like:

- Visual obscurants (smoke, snow, low light)

- Camouflage and decoys

- Motion blur and vibration

- Sensor damage and partial occlusion

Those aren’t “data science problems.” They’re range problems, because you need safe space to run repeated sorties, collect telemetry, and stress the system under realistic interference and weather.

The hard part: AI performance changes under EW pressure

Here’s what I’ve found when teams test autonomy in constrained conditions: the model’s accuracy isn’t the only metric that matters. Under jamming and deception, the most important behaviors are:

- Confidence calibration: Does the system know when it doesn’t know?

- Degradation mode: Does it fail safely, or fail “confidently wrong”?

- Recovery behavior: Does it re-acquire navigation and targets responsibly?

- Human override: Can an operator intervene quickly and predictably?

Those behaviors are exactly what training ranges need to validate—especially for special operations units that operate dispersed, with limited support.

Training pipelines are adapting, but ranges are the bottleneck

Answer first: The U.S. is updating curricula for EW and robotics, but range access is limiting how fast those skills can be taught and evaluated.

The reporting describes several concrete moves:

- A new Army tactical SIGINT and electronic warfare course pilot ran July–October with 15 students, with a new class planned for May.

- A new robotics detachment launched in March 2024.

- A robot technician specialty is being developed and trained.

This is the right direction: training isn’t just “how to fly a drone.” It’s how to sense, decide, and act when your systems are being spoofed, jammed, or lured by decoys.

Why “build-and-modify in the field” needs spectrum space

One of the most overlooked lines in the article is about needing jammable space to practice creating and modifying drones on the battlefield. That’s a major shift.

Modern drone ops are increasingly a continuous engineering problem:

- Update firmware to handle a new jammer

- Swap payloads for different sensing

- Adjust autonomy parameters

- Change frequency plans or emission discipline

If you can only test in sterilized spectrum conditions, you train people to be good at peacetime drone flying—not wartime drone fighting.

The U.S. test model is still built around “rare GPS loss”

The FAA issued 10 advisories of pending GPS interruptions in 2025, per the reporting. That cadence reflects an older assumption: GPS denial is exceptional and tightly controlled.

But precision weapons, navigation aids, timing systems, and commercial infrastructure have become deeply coupled to GPS. That coupling created legitimate caution around jamming. The problem is that adversaries don’t share our caution, and modern conflicts are demonstrating persistent interference.

The result is a mismatch:

- Our weapons and training assumed long-term GPS advantage.

- Our process assumes GPS disruption should be rare.

- The battlefield assumes GPS disruption is constant.

What “AI-realistic” EW drone ranges should include

Answer first: An AI-realistic training range isn’t “more jamming.” It’s a controlled environment that supports repeatable, instrumented, ethically bounded testing of autonomy under contested spectrum conditions.

If you’re planning ranges, acquiring EW systems, or building autonomy for drones, here’s what to ask for.

1) Contested PNT as a standard training condition

“PNT” (Positioning, Navigation, and Timing) denial is no longer a special event. Ranges should support:

- GPS jamming and GPS spoofing (separately, because they create different failure modes)

- Timing disruptions that affect network synchronization

- Instrumented truth data so teams can compare what happened vs. what the system thought happened

2) Spectrum complexity, not just power

Real conflicts include multiple emitters, overlapping bands, intermittent bursts, and deception. AI-enabled EW increasingly depends on signal classification and emitter identification, which benefits from:

- Multiple jammer types (noise, barrage, deceptive)

- Variable duty cycles

- Realistic RF clutter

- Red-team emitters that force classification models to generalize

3) Telemetry-rich instrumentation for AI evaluation

Autonomy needs measurement. Ranges should provide:

- High-resolution logs (navigation state, perception outputs, confidence scores)

- Ground truth annotation for targets and non-targets

- After-action replay tooling that supports model retraining and error analysis

A memorable rule: If you can’t replay it, you can’t improve it.

4) Policy guardrails that scale testing safely

This is where “lead generation” meets practical value: many defense and national security organizations need partners who understand both AI and compliance.

Scalable range policy typically requires:

- Clear time-boxed corridors and NOTAM-style advisories

- Geo-fenced power limits and monitoring

- Coordination playbooks with FAA/FCC and local stakeholders

- Independent verification that emissions stayed within bounds

This is not red tape for its own sake. It’s how you earn the right to train realistically more often.

“People also ask” (and what actually matters)

Can’t we simulate jamming in a lab or with digital twins?

Answer: You can simulate pieces, but you can’t replace field testing. Lab setups rarely reproduce multipath, terrain masking, dynamic clutter, or operator behavior under stress. Digital twins help, but they need real-world data to stay honest.

Why does AI make EW training harder?

Answer: AI systems introduce probabilistic outputs and confidence behaviors. Under EW pressure, you’re validating not just “does it work,” but “does it degrade predictably, explainably, and safely.” That demands instrumented, repeatable trials.

Why is special operations driving this?

Answer: Special operators often face the most constrained comms, operate with less infrastructure, and adopt small unmanned systems quickly. They also need training pipelines that integrate drones, SIGINT, EW, and autonomy as one operational problem.

What this means for defense leaders and industry partners

Expanded EW drone ranges are not a “nice to have.” They’re infrastructure for an AI-enabled force. If the U.S. wants autonomous systems that work in real conflict—not demos—then training and testing capacity has to grow beyond a couple of sites and a handful of scheduled interruptions.

From a program perspective, the best teams will treat ranges as part of the product:

- Build autonomy with measurable degradation modes

- Design EW features with operator trust as a requirement

- Plan for compliance and coordination early, not after the prototype works

If you’re responsible for AI in defense & national security—whether that’s autonomy, EW analytics, or training—this is a good moment to audit your own readiness question: How many hours per quarter can your team test in GPS- and comms-denied conditions that look like a real fight?

If the answer is “not many,” your next step is straightforward: align range access, instrumentation, and safety policy into one roadmap. The rest of the AI strategy depends on it.