An F-22 pilot controlled an MQ-20 drone wingman in flight. Here’s what it signals about AI-enabled teaming, comms, and CCA readiness.

F-22 Pilot Controls Drone Wingman: What AI Enables

A single-seat fighter is already a high-cognitive-load job. Now add a second aircraft—uncrewed—into the mix.

That’s why the most interesting part of the recent F-22 demonstration isn’t “a pilot flew a drone.” It’s how close we are to a practical model of human-machine teaming: a pilot commanding an uncrewed “wingman” with a tablet interface during a live flight over the Nevada Test and Training Range (Oct. 21), using government-owned, non-proprietary communications components demonstrated by an industry team.

In the AI in Defense & National Security series, I keep coming back to the same point: AI matters in defense when it compresses decision time without adding pilot workload or brittle dependencies. This flight test—F-22 + MQ‑20 Avenger—puts that reality on the runway.

Why this F-22 drone wingman test is a milestone

This matters because it signals a shift from “autonomy demos” to “operationally plausible workflows.” A fighter pilot doesn’t have time for a science project in the cockpit. If uncrewed aircraft are going to be worth buying at scale, they have to fit inside real tactics, real timelines, and real human attention limits.

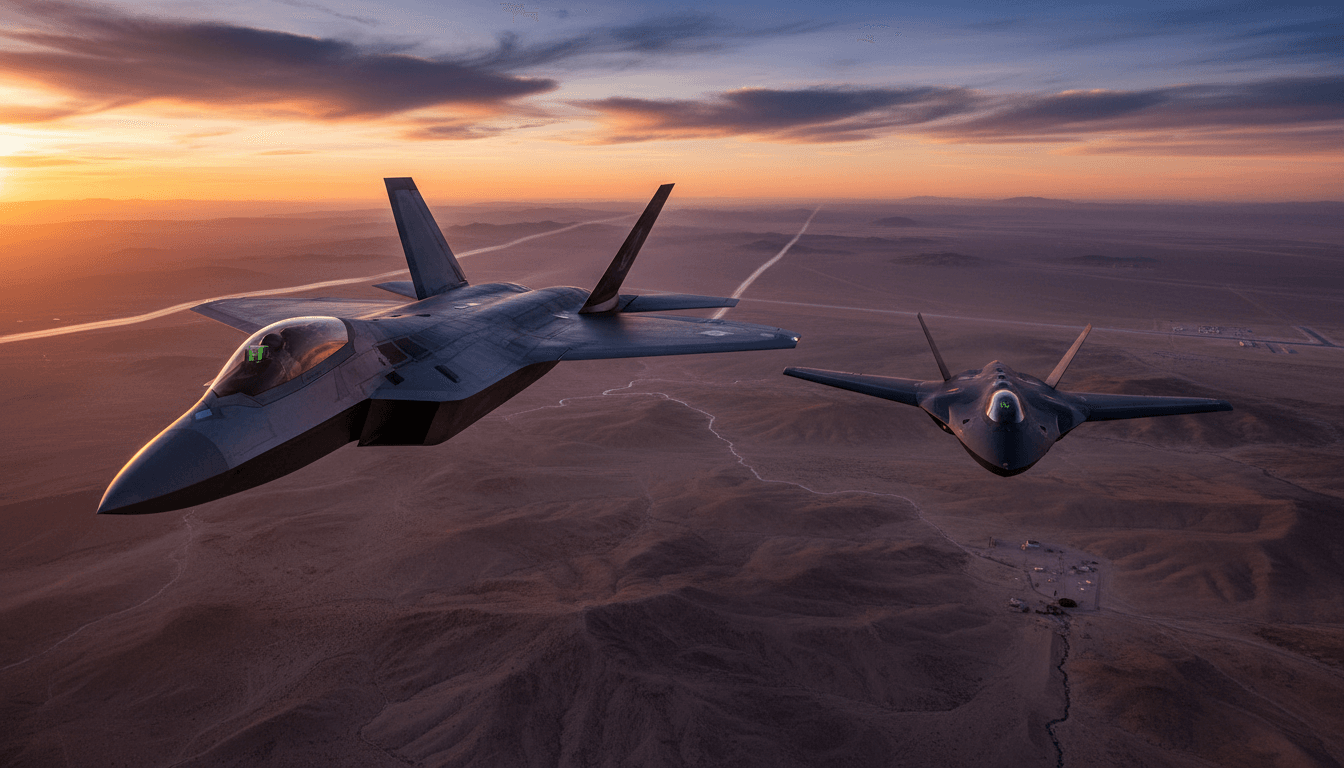

The demonstration (announced mid-November and timed with the Dubai Airshow) paired:

- F-22 Raptor as the crewed command platform

- MQ‑20 Avenger as the uncrewed surrogate (a jet-powered platform General Atomics already operates)

- Datalinks and software-defined radios provided by L3Harris

- Open radio architecture integration highlighted by Lockheed Martin

The headline is simple: in-flight command and control of an uncrewed combat aircraft from an F-22 cockpit. The deeper story is about what the Air Force is really testing—interfaces, communications, and authority allocation—because those are what make collaborative combat aircraft (CCA) usable.

The “tablet in the cockpit” detail isn’t trivial

A tablet is an implicit design decision: it suggests the service and industry are looking for a control concept that’s familiar, rapidly iterated, and decoupled from a decades-old avionics stack.

But it also raises hard questions the program has to answer before CCAs become routine:

- How do you prevent interface-induced distraction during high-G, high-threat phases?

- What tasks are safe to push to “heads-down” interactions, and which must remain “heads-up”?

- How do you certify and secure an interface that evolves like software, not like traditional aircraft hardware?

If the interface isn’t right, none of the autonomy behind it matters.

Where AI actually fits in crewed–uncrewed teaming

AI’s job in a drone wingman concept is to turn commander intent into safe, timely action—without constant micromanagement. That means autonomy isn’t a single feature; it’s a stack of capabilities that reduce how often a pilot must intervene.

Here’s the clean way to think about it:

AI handles “how,” humans decide “what” and “why”

In realistic air combat, the human should stay responsible for:

- Mission intent (what effect are we trying to achieve?)

- Rules of engagement and authorities (what is permitted?)

- Risk acceptance (what are we willing to lose?)

The uncrewed system—enabled by autonomy and AI—should handle:

- Formation management and deconfliction

- Route planning around threats and constraints

- Sensor management (where to look, when to revisit)

- Timing and coordination (arrive, hold, rejoin, disperse)

A strong CCA concept turns pilot inputs into things like:

- “Go to that point and hold.”

- “Screen my left at 20 miles.”

- “Run passive sensing and report tracks.”

- “Decoy that emitter and rejoin when complete.”

Those are intent-level commands. The AI work is everything underneath.

Autonomy is also about graceful failure

The best autonomy is boring when it fails. In contested environments, links degrade, sensors lie, GPS is denied, and adversaries spoof and jam.

So autonomy isn’t only “do more on your own.” It’s:

- Maintain safe behavior under uncertainty

- Fall back to pre-briefed playbooks when comms drop

- Avoid forcing the pilot to babysit edge cases

If CCAs require a pilot to constantly rescue them, they’re not wingmen—they’re liabilities.

The real fight: communications, interoperability, and trust

Human-machine teaming succeeds or fails on three non-negotiables: resilient comms, interoperable architecture, and calibrated trust. The press details about “non-proprietary, U.S. government-owned communications capabilities” and “open radio architectures” are the quiet center of gravity here.

Interoperability is a warfighting requirement, not a procurement preference

A CCA ecosystem only scales if different primes and different drone designs can:

- join the same mission network,

- accept mission tasks using shared message standards,

- and interoperate without one vendor controlling the whole stack.

The Air Force’s CCA plan is headed toward competitive increments and rapid iteration. That’s incompatible with closed, vendor-locked ecosystems.

Open architectures reduce long-term integration cost and shorten the time from “new threat” to “new tactic.” That’s exactly where AI-enabled mission planning and autonomy updates should live.

“Trust” is built by predictability, not hype

Pilots don’t trust autonomy because a briefing slide says they should. They trust it when it behaves consistently across edge cases.

Trust grows when the system can answer:

- What are you doing?

- Why are you doing it?

- What will you do next if conditions change?

This is where explainable behaviors and transparent autonomy policies matter more than flashy demos. For cockpit use, predictable autonomy beats clever autonomy.

What this means for the CCA race and the Air Force’s fighter roadmap

This demonstration is also a competitive signal. General Atomics and Anduril are in a visible sprint toward the Air Force’s CCA production decision expected in 2026. Flying prototypes quickly isn’t just marketing—it’s how you prove you can execute the program’s pace.

But the F-22 integration angle matters for strategy. The Air Force has stated (in its planning documents) that:

- F-22 is the threshold platform for early CCA integration, and

- CCAs later support next-generation fighters like the F-47, with first flight expected in 2028.

That sequencing tells you what the service values:

- Prove human-machine teaming with an elite air dominance platform.

- Mature tactics, interfaces, and mission autonomy before the next-generation fighter arrives.

- Carry those lessons into F-47-era concepts of employment.

From a national security standpoint, this is the right order. You don’t want your next-generation aircraft to be the first place you learn basic teaming behaviors.

A practical view of what CCAs will do first

Early CCAs are most likely to deliver value in missions where they can be useful even with conservative autonomy:

- Forward sensing and passive detection (extend the sensing perimeter)

- Communications relay in cluttered or denied environments

- Decoy and deception (force adversary emissions, waste interceptors)

- Stand-in jamming with preplanned behaviors

These roles reduce risk to crewed aircraft and don’t require “full autonomy.” They require reliable autonomy.

Implementation checklist: what defense teams should build for now

If you’re developing autonomy, mission software, datalinks, or cockpit tools, the bar is shifting toward operational integration. Here’s what I’d prioritize based on where these programs are heading.

1) Design autonomy around intent, not tasks

The winning systems won’t be the ones with the longest feature list. They’ll be the ones that translate a small set of pilot commands into robust behaviors.

Good intent-level primitives usually include:

go-to / hold / rejoinscreen / escort / trailsearch / classify / trackdecoy / jam / suppressabort / return / safe

2) Treat contested comms as the default

Build for:

- intermittent connectivity,

- low bandwidth,

- high latency,

- and adversarial interference.

If your autonomy needs perfect links, it won’t survive contact.

3) Make “failure modes” part of the user experience

A pilot should know—immediately—whether the drone is:

- executing as planned,

- degraded but safe,

- or in a fallback plan.

This is interface design, not just autonomy engineering.

4) Bake security into the autonomy pipeline

CCAs are software-defined aircraft. That makes them powerful—and attackable.

Practical requirements that programs should assume include:

- signed mission packages,

- authenticated command messages,

- tamper-evident logs,

- and cyber-resilient update mechanisms.

If you can’t prove integrity, you can’t scale trust.

People also ask: what’s the difference between a “drone wingman” and a normal UAV?

A drone wingman (CCA concept) is meant to operate as part of a team, not as a remotely piloted asset needing constant attention. Traditional UAV operations often center on dedicated crews, long planning cycles, and single-mission tasking. A wingman model centers on:

- dynamic tasking during flight,

- intent-based control,

- and autonomy that reduces operator workload.

In other words: the “wingman” isn’t about being uncrewed. It’s about being teamable.

Where this goes next (and what to watch in 2026)

The next big proof point isn’t another one-off linkup. It’s repeatability at scale: multiple CCAs, multiple mission sets, multiple vendor stacks, and degraded communications—without the pilot drowning in management overhead.

The 2026 production-design decision will push the ecosystem from demonstration to discipline. When money meets manufacturing, the real differentiators will be boring but decisive: integration cost, upgrade cadence, cyber posture, and how quickly new tactics can be fielded.

For leaders tracking AI in defense and national security, the most useful question to ask now is simple: Can your autonomy and mission software survive the realities of contested operations while staying intuitive enough for a single-seat cockpit? If the answer is “not yet,” that’s not failure—it’s the work.

If you’re building toward CCA integration, mission autonomy, or resilient command-and-control, the fastest path to credibility is showing how your system behaves on the worst day, not the best day. What would your drone do when the link drops, the sensor disagrees, and the pilot is too busy to help?