Europe’s “drone wall” shows how AI-enabled counter‑UAS can scale across borders—if sensor fusion, interoperability, and cost-per-kill are designed right.

Europe’s Drone Wall: AI Defense That Scales Fast

A 2,000-kilometer border can’t be protected with “a few radars and good intentions.” One counter-drone industry report put the math bluntly: covering that distance could require 200+ radar sites, and even then small drones may only be detected 3–10 km out—meaning once they slip past the first line, tracking often collapses into costly, reactive fighter scrambles.

Europe’s proposed “drone wall” is a direct response to that ugly geometry—and it’s also one of the clearest real-world case studies for this series on AI in Defense & National Security. The core idea isn’t a literal wall. It’s a network: sensors that can spot small drones, AI that can fuse and classify signals in real time, and low-cost ways to stop intruders before a swarm turns into a strategic headache.

The most useful lesson for defense leaders and industry teams right now: counter‑UAS isn’t a single system purchase. It’s an AI-enabled operations stack that must be tested, iterated, and fielded on a tempo closer to software than traditional air defense.

The “drone wall” is really an AI-enabled counter‑UAS stack

The fastest way to understand the drone wall is to treat it like a layered security architecture—similar to cyber defense—rather than like a classic air-defense battery.

At a practical level, an AI-enabled counter‑UAS stack has five jobs:

- Detect small, low-RCS drones early enough to act.

- Track them continuously, even when they duck behind terrain or clutter.

- Classify what they are and what they’re doing (bird vs quadcopter vs one-way attack drone).

- Decide what response is appropriate (jam, spoof, intercept, or monitor).

- Engage at a cost that makes sense when threats arrive in volume.

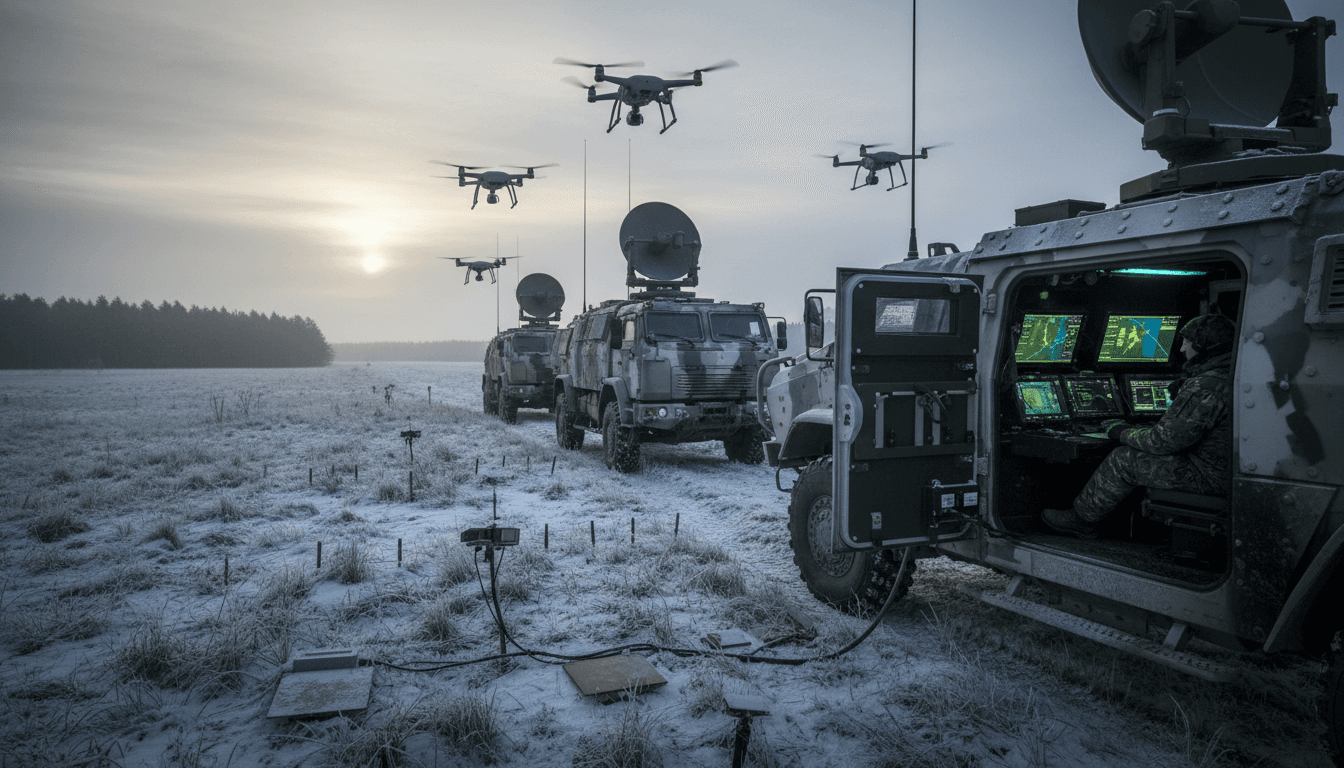

Europe’s push emphasizes exactly those pieces: more sensors (including acoustic), more mobility (truck-mounted and unmanned platforms), more automation (semi-autonomous engagement), and cheaper intercept options designed for the swarm era.

Here’s the key stance I’ll take: the drone wall succeeds or fails on AI-driven command and control (C2). Hardware matters, but without fast fusion and decision support, you end up with isolated gadgets that each work fine in a demo—and underperform together in a real incursion.

Why mobile sensors matter more than “bigger radar”

Traditional air-defense radar was built to see fast aircraft and missiles. Small drones are a different problem: lower signatures, lower altitude, and a tendency to blend into background clutter.

The drone wall concept leans into distributed sensing—a mix of fixed and mobile nodes—to reduce blind spots:

- Truck-mounted sensors that can reposition as threat patterns change

- Drones detecting drones (airborne nodes that create flexible coverage)

- Coastal and riverine sensors carried by manned/unmanned boats

- Fixed acoustic sensing that can persist where radar coverage is weak

AI is what makes this workable. A distributed mesh produces noisy, partial observations. Sensor fusion is the difference between “we heard something” and “we have a track with confidence and a predicted intercept window.”

The real constraint is cost per kill—and AI is how you manage it

Drone incursions become strategically dangerous when they’re cheap enough to repeat and numerous enough to saturate defenders.

The drone wall conversation is shaped by a basic reality learned in Ukraine: expensive interceptors don’t scale against inexpensive mass. When a defender spends orders of magnitude more per shot than an attacker spends per drone, the attacker gets to choose the tempo.

This is where AI shows up in two non-negotiable ways:

- Engagement optimization: Decide which threats truly need kinetic engagement vs electronic warfare vs monitoring.

- Operator scaling: Automate routine steps so one operator can manage multiple engagements.

One Estonian-developed concept described in the source material pushes toward semi-automatic operation specifically because “one operator per drone” is a losing staffing model when drones arrive in groups.

Semi-autonomous engagement isn’t a luxury; it’s staffing math

Counter‑UAS teams quickly hit two ceilings:

- Human attention: how many tracks can an operator manage correctly under stress?

- Crew availability: how many trained operators can you field 24/7 across long borders?

Semi-autonomous engagement—where the system proposes actions and shortens the “detect-to-decision” loop—directly addresses both. Done right, AI doesn’t remove humans from the loop; it removes humans from the bottlenecks.

Practical design pattern that works:

- AI does triage (classify, prioritize, recommend)

- Humans do authorization (rules of engagement, escalation, fail-safes)

- Systems do execution (jamming, cueing interceptors, navigation)

If you’re building procurement requirements in 2026, bake this in: measure “operators per defended kilometer” as a first-class performance metric.

Estonia’s startups show what “weeks not months” looks like

The drone wall effort is associated with EU-level coordination, but the most actionable part is happening at the edge: small countries and nimble firms iterating with frontline feedback.

Estonia is a telling example because it sits on NATO’s eastern flank and has the kind of tech ecosystem that can move fast. The model described in the source is not “build for five years, then field.” It’s:

- Collaborate with operational units (including Ukrainian commanders)

- Prototype rapidly

- Test in realistic environments

- Adjust hardware and models

- Ship something fieldable at a defendable price point

That “tempo” aligns with how modern AI-enabled defense systems should be delivered.

Interoperability is the hidden make-or-break requirement

Europe’s drone wall overlaps geographically and operationally with NATO’s eastern defense initiatives. That overlap creates a hard requirement: interoperable counter‑UAS C2.

Interoperability isn’t just about radios and message formats. In AI-enabled air defense, it also includes:

- Shared track quality standards: what counts as a “confirmed track”?

- Model governance: what training data is allowed, who signs off on updates?

- Confidence and uncertainty reporting: can commanders see why the AI recommends action?

- Deconfliction: preventing friendly drones, aircraft, and EW effects from colliding

If EU members buy a patchwork of systems that can’t share tracks and cues, they’ll recreate the classic problem: local success, regional fragility.

What an AI-powered drone wall must include (or it won’t scale)

A credible “drone wall” needs more than gadgets placed along a border. It needs an architecture that anticipates swarms, spoofing, emissions control, and rapid adversary adaptation.

Here are the components I’d insist on if I were evaluating or advising a program like this.

1) Multi-sensor fusion that survives clutter

Answer first: You won’t track small drones reliably with one sensor type.

A real drone wall should fuse:

- radar (where it works)

- RF detection (when drones emit)

- EO/IR (for confirmation and ID)

- acoustic (for persistence in radar-poor zones)

AI should combine them into a single, explainable picture: track ID, heading, predicted path, and confidence.

2) Edge AI for low-latency decisions

Answer first: The best place to run many counter‑UAS models is near the sensor, not in a distant cloud.

Borders and remote sites can’t depend on perfect backhaul. Edge AI reduces latency and keeps the system operating under jamming or network degradation.

3) Electronic warfare that’s managed like spectrum operations

Answer first: EW isn’t “turn on a jammer.” It’s a managed campaign that can cause friendly disruption.

An AI-assisted drone wall should model:

- jammer coverage and side effects

- risk to friendly comms/GNSS

- escalation rules (when spoofing becomes jamming)

4) Low-cost kinetic options for when EW fails

Answer first: You need cheap interceptors because some drones will be autonomous, hardened, or preprogrammed.

The source material highlights the push for more affordable interceptors and drone-on-drone approaches. The strategic logic is simple: your cost curve must be competitive with the attacker’s.

5) A continuous test-and-update pipeline

Answer first: Counter‑UAS is an adaptation contest, so model updates must be routine and governed.

Treat it like a secure MLOps pipeline:

- red-team data collection (new drone profiles, new tactics)

- retraining and validation

- controlled rollout by region

- audit logs and rollback capability

If updates require a months-long certification cycle, adversaries will run circles around the system.

Common “People also ask” questions defense teams should answer now

Is a drone wall even feasible in a few years?

Technically, yes—if “drone wall” means a layered network with incremental coverage. Politically and programmatically, the risk is timelines drifting because interoperability, procurement, and governance aren’t solved early.

Why not just use fighter jets or traditional air defense?

Because it doesn’t scale. Fighter scrambles are expensive and poorly suited to persistent, high-volume, low-cost incursions. Traditional air defense is designed for different targets and often uses interceptors that are economically mismatched to cheap drones.

Where does AI add the most value in counter‑UAS?

In three places:

- Sensor fusion (turning noisy signals into actionable tracks)

- Classification and prioritization (reducing false alarms and workload)

- Decision support (shortening detect-to-engage while keeping humans in control)

What this means for AI in Defense & National Security teams

Europe’s drone wall effort is a preview of where national security AI is headed: persistent surveillance, distributed autonomy, and coalition-scale coordination. It’s also a warning: buying sensors and effectors is the easy part; building the AI-enabled C2 that ties them together is where programs win or stall.

If you’re leading a defense innovation team, a prime contractor portfolio, or a government acquisition shop, focus your next planning cycle on these actions:

- Write requirements around outcomes, not devices (tracks maintained, operator load, cost per engagement)

- Prioritize interoperability early (shared track formats, confidence reporting, deconfliction)

- Build a governed update pipeline so counter‑UAS models can evolve at operational speed

- Plan for mixed defenses (EW + kinetic + “hunter” drones), because attackers won’t stick to one profile

The big question for 2026 planning isn’t whether Europe will build a drone wall. It’s whether allied nations can agree on the AI-enabled command-and-control backbone that makes a wall behave like a system—rather than a collection of parts.

If you’re evaluating counter‑UAS architectures or planning an AI roadmap for border security, what’s the one integration constraint you expect to break first: data sharing, spectrum management, or operator workload?