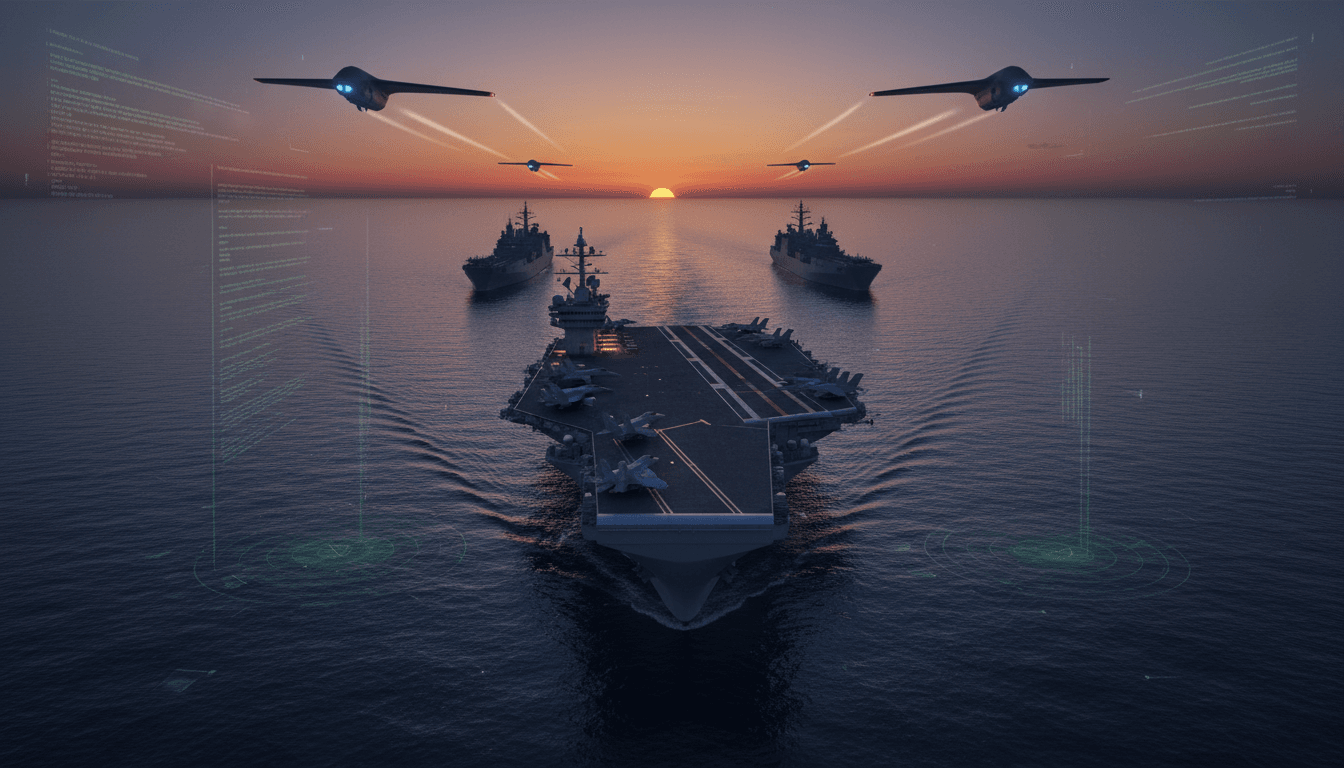

China’s naval surge is a tempo problem. Here’s how AI-driven intelligence and autonomy help the U.S. and allies monitor, deter, and respond faster.

China’s Navy Surge: The AI Edge the U.S. Needs

China isn’t just adding hulls to the water. It’s compressing the timeline for maritime power in a way that changes how the U.S. and its allies must think about deterrence, warning, and wartime sustainment.

In November, China commissioned the 80,000-ton Fujian, its third aircraft carrier and the first in its fleet built with electromagnetic catapults. Around the same time, the Sichuan, a major amphibious assault ship designed to operate helicopters and large drones, completed initial sea trials and is expected to deploy next year. Pair that with China’s shipbuilding ecosystem—commercial and military intertwined—and the strategic message is pretty direct: Beijing intends to be able to generate naval combat power faster, farther from home, and for longer.

For this AI in Defense & National Security series, the interesting part isn’t only the platforms. It’s what those platforms force everyone else to do: sense more, decide faster, and manage risk at scale. That’s an AI problem as much as it’s a shipbuilding problem.

China’s “world-class navy” is about tempo, not prestige

China’s naval modernization is often discussed as a prestige project—carriers as national trophies. That’s a distraction. The real story is operational tempo: China is building the kind of fleet that can keep pressure on multiple flashpoints while holding enough capacity in reserve to surge.

Public estimates cited in the source reporting put China at 1,000+ vessels, including roughly 370 warships and submarines in its “battle force.” China is also widely assessed to be on track for a 425-ship fleet by 2030, while the U.S. Navy sits under 300 deployable battle-force ships. Even if you believe the U.S. remains qualitatively superior in key classes, the math matters because quantity becomes a form of resilience in a long fight.

Here’s the strategic shift: if a peer can replace ships, missiles, and merchant tonnage faster than you can, deterrence no longer rests only on “winning the first battle.” It rests on outlasting the second and third.

Why Fujian and Sichuan matter differently

The Fujian is symbolically important and operationally meaningful: electromagnetic catapults support heavier aircraft loads, higher sortie generation potential, and a path to more sophisticated carrier air wings over time.

But the Sichuan may be the more relevant chess piece for regional contingencies. Amphibious ships, drone-capable assault decks, and aviation support are directly tied to coercion scenarios—especially blockade, island seizure, and Taiwan-related operations. If you’re planning to challenge access, complicate reinforcement, and impose costs close to your coastline, assault ships and the systems that coordinate them are practical tools.

The takeaway: carriers draw headlines; amphibious and drone-capable ships change planning assumptions.

The real competition: industrial base plus algorithmic advantage

Most debates frame the problem as “U.S. shipbuilding vs. China shipbuilding.” That’s true, but incomplete.

A modern fleet is a data-generating machine. Every deployment, sensor sweep, maintenance cycle, and exercise produces information that can improve readiness and tactics—if you can ingest and interpret it quickly. This is where AI in national security stops being abstract.

China’s advantage is structural:

- Scale in shipbuilding: China’s global commercial shipbuilding share reportedly grew from about 5% (1999) to roughly 50%, while the U.S. builds <1% of commercial ships.

- Dual-use integration: commercial yards and suppliers can reinforce military output.

- Geography: proximity to likely contingencies reduces transit time and eases repair and resupply.

The U.S. advantage can’t be only “build more ships” because that’s a decade-plus project. The near-term edge has to come from better decisions per unit time.

A blunt way to say it: industrial capacity wins long wars; AI buys you time not to lose the short one.

AI’s role in tracking the PLAN: from ISR overload to decision advantage

If you talk to practitioners, the problem isn’t that the U.S. lacks sensors. The problem is the opposite: too many collections, too many feeds, too many reports—then a human staff tries to stitch it into a coherent picture.

AI-enabled intelligence analysis is the only scalable way to keep pace with a fast-growing fleet operating across wider geographies.

What “AI-driven maritime domain awareness” actually means

Maritime domain awareness isn’t one system. It’s a pipeline:

- Collection: satellite imagery, SAR, AIS, radar, acoustic arrays, SIGINT, open-source maritime reporting.

- Fusion: align time, location, and identity across sources.

- Behavior modeling: distinguish routine patterns from operational preparation.

- Forecasting: estimate likely routes, replenishment cycles, exercise-to-operation transitions.

- Alerting and tasking: cue sensors, redirect collectors, and prioritize analyst time.

AI helps most at steps 2–5.

Practical AI applications for naval threat monitoring

These are the use cases I see as most immediately valuable for Indo-Pacific security teams:

- Automated vessel classification from imagery (including recognizing hull forms, deck layouts, and likely mission packages)

- Anomaly detection on deployments (changes in sortie rhythm, unusual replenishment behavior, altered escort composition)

- Predictive logistics modeling (where a carrier strike group can realistically be in 48–96 hours based on speed, replenishment, and weather)

- Operational pattern discovery using multi-year exercise data (who trains with whom, how often, and in what configurations)

- Risk-scored alerts that explain “why this is flagged,” not just “this is flagged”

Done well, this doesn’t replace analysts. It gives them what they’ve always wanted: fewer false alarms and faster confidence.

A fleet that moves faster than your analysis cycle isn’t just a threat—it’s a tool for strategic surprise.

Autonomous systems and “drone carrier” dynamics change naval math

The Sichuan’s drone-friendly design highlights where naval warfare is trending: more uncrewed aircraft for ISR, strike support, decoys, and saturation.

That shifts the balance in three ways:

- More sensors at the edge: uncrewed systems extend detection and targeting.

- More complex command-and-control: managing swarms and mixed formations increases cognitive load.

- More deception opportunities: decoys, emissions tricks, and multi-axis probes become cheaper.

AI is central because autonomy isn’t only “the drone flies itself.” It’s also:

- mission planning (route and timing optimization)

- contested communications management (what happens when datalinks degrade)

- target recognition and prioritization

- deconfliction (keeping friendly assets from colliding or duplicating effort)

The uncomfortable truth about autonomy in a Pacific fight

Autonomy creates capability, but it also creates new failure modes. In a high-stakes maritime theater, the losing side may be the one that:

- can’t validate target ID fast enough,

- can’t manage spectrum contention,

- or can’t recover from a software-induced operational pause.

That’s why “AI in defense” can’t be treated like an app rollout. It’s a safety, assurance, and governance program with real wartime consequences.

What U.S. and allied leaders should prioritize in 2026

Shipbuilding policy matters, and the U.S. has signaled urgency with an executive order aimed at restoring maritime dominance, including an Office of Shipbuilding and a Maritime Action Plan timeline. But even aggressive industrial reform won’t change fleet size fast enough to solve the next 24 months.

So the priority list for 2026 should be pragmatic: increase deterrence now by tightening the sense-decide-act loop.

1) Build an AI-ready intelligence workflow (not just models)

AI programs fail when they’re bolted onto old processes. The workflow has to change:

- standardize data schemas across collectors

- tag and score collection quality

- create audit trails for model outputs

- train analysts to interrogate model reasoning

If your AI can’t be explained to an operator at 0200 during an unfolding incident, it’s not operational.

2) Treat maritime analytics as a joint-and-allied product

A single nation’s picture will be partial. High-confidence maritime domain awareness in the Pacific is inherently allied.

That means:

- agreed data-sharing rules that actually work during crises

- interoperable alert formats and confidence scoring

- shared “known patterns” libraries for exercises and deployments

3) Harden autonomy and C2 against deception

China’s growing fleet will be paired with cyber, electronic warfare, and information operations designed to degrade decision-making.

The defensive posture should assume:

- poisoned data inputs

- spoofed maritime identity signals

- EMCON tactics intended to produce uncertainty

AI systems need red-teaming, adversarial testing, and fallback modes that degrade gracefully.

4) Use AI to improve readiness, not only warfighting

Here’s a non-obvious win: AI can increase available combat power by reducing time in maintenance and improving parts forecasting.

If you recover even 5–10% more operational availability across key ship classes, you create deterrence value without launching a single new hull.

People also ask: does China already have a better navy than the U.S.?

Not in the ways that matter most for high-end naval combat—yet.

The U.S. still holds meaningful advantages in areas like undersea warfare, carrier aviation experience, and networked joint operations. But China doesn’t need to be “better overall” to change the strategic equation. It needs to be good enough in enough places, with enough ships, close enough to the fight, to impose unacceptable costs and delay response.

That’s why the relevant question for planners is sharper:

Can the U.S. and allies maintain decision advantage and sustainable presence as China increases fleet size and sophistication?

The lead-generation reality: the winners will operationalize AI, not admire it

A lot of organizations talk about AI-enabled defense like it’s a procurement item. It’s not. It’s an operating model.

If your team is responsible for security, intelligence, maritime risk, or defense tech strategy, you should be pushing for three measurable outcomes:

- Faster detection-to-assessment time for significant PLAN movements

- Higher-confidence fusion across sensor sources (with documented uncertainty)

- More resilient operations when comms are degraded or data is contested

If you’re not measuring those, you’re not building an advantage.

The next phase of naval competition in the Pacific will be decided by fleets—but also by the algorithms that interpret fleet behavior, protect autonomy from deception, and keep commanders inside the opponent’s decision cycle. Where is your organization on that maturity curve right now?